Review: Midnight Rising by Tony Horwitz

Tony Horwitz. Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War.

Tony Horwitz. Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War.

New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2011.

Pp. xii, 365.

Click here for an audio clip of the book.

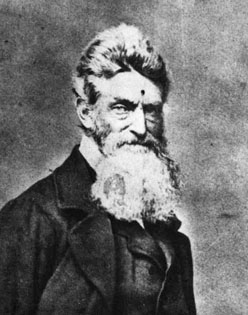

With penetrating eyes, tussled greying hair, and a flowing white beard, John Brown strikes a memorable image. His impressive pose, captured in several remarkable photographs, demonstrated his resolve and hinted at the later acts that would immortalize him. Tony Horwitz—most likely familiar to readers for his work Confederates in the Attic—takes up the subject of Brown, his followers and their crusade against slavery in Midnight Rising. Haunting is the best description of this highly readable, rapidly paced book. Horwitz’s writing is insightful and wide-ranging, and his narrative humanizes and illuminates an event that is shrouded in myth.

Beginning at the end, Horwitz prefaces his study on the night of October 16, 1859. The small town of Harpers Ferry—nestled in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers—was home to one of the two national armories and located in the northern most reaches of the slave state of Virginia. Harpers Ferry’s strategic location and substantial weapons’ repository attracted Brown. That fall evening eighteen black and white men, led by their fiery Captain, quickly captured the arsenal. This act set into motion an elaborate plan of which Brown had first conceived a decade earlier and for which the men had prepared the past year. The party of nineteen composed the main bulk of the Provisional Army of the United States who, guided by a constitution and a “Declaration of Liberty,” were prepared to erect a revolutionary government and free the South’s enslaved population. As readers know, Brown’s mission ended on the morning of the eighteenth after a detachment of marines moved on Harpers Ferry. Those not killed in the raid would hang on the gallows.

Beginning at the end, Horwitz prefaces his study on the night of October 16, 1859. The small town of Harpers Ferry—nestled in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers—was home to one of the two national armories and located in the northern most reaches of the slave state of Virginia. Harpers Ferry’s strategic location and substantial weapons’ repository attracted Brown. That fall evening eighteen black and white men, led by their fiery Captain, quickly captured the arsenal. This act set into motion an elaborate plan of which Brown had first conceived a decade earlier and for which the men had prepared the past year. The party of nineteen composed the main bulk of the Provisional Army of the United States who, guided by a constitution and a “Declaration of Liberty,” were prepared to erect a revolutionary government and free the South’s enslaved population. As readers know, Brown’s mission ended on the morning of the eighteenth after a detachment of marines moved on Harpers Ferry. Those not killed in the raid would hang on the gallows.

Within a month of Harpers Ferry Americans actively pondered the event’s legacy and variously assigned it the labels of “Insurrection,” “Rebellion,” or “Crusade.” Just why John Brown and his men acted as they did and how this event connected to the Civil War are the questions driving Horwitz’s book. Audiences familiar with his other works should note that he departs from his traditional approach. Previously, Horwitz immersed himself in his subject capturing the murky waters between history and myth crafting his story through journalistic narrative and autobiography. I should say that I was initially drawn to this book hoping for his past approach. Instead, Midnight Rising represents the author’s first attempt at more traditional historical writing, though with a focus more on narrative than argument. That said, Horwitz’s gift of capturing individuals’ characters and understanding meta-events at the micro-level come through clearly, making the work largely successful and quite enjoyable.

Midnight Rising proceeds chronologically and is arranged into three parts, underpinned by thirteen chapters. Framing his discussion within the political and social strife of the nineteenth century, Brown is aligned with a burgeoning abolitionist movement. Indeed, over the course of his life he drew support from Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman among others. The deeply religious Brown believed in racial equality and was energized by national debates over slavery’s extension. At midcentury, struggling to settle his finances and his family, Brown’s commitment to ending slavery assumed increased urgency. Several members of the Brown family had already settled in Kansas, a territory embroiled in a conflict that would decide its future status as a free or slave state.

Midnight Rising proceeds chronologically and is arranged into three parts, underpinned by thirteen chapters. Framing his discussion within the political and social strife of the nineteenth century, Brown is aligned with a burgeoning abolitionist movement. Indeed, over the course of his life he drew support from Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman among others. The deeply religious Brown believed in racial equality and was energized by national debates over slavery’s extension. At midcentury, struggling to settle his finances and his family, Brown’s commitment to ending slavery assumed increased urgency. Several members of the Brown family had already settled in Kansas, a territory embroiled in a conflict that would decide its future status as a free or slave state.

Horwitz follows Brown and the members of his clan into the contested territory to discover how the committed abolitionist transformed his staunch beliefs into a Gideon-like mission. In May 1856, the contest in Kansas boiled over. Proslavery forces sacked Lawrence and, to Brown’s chagrin, free-staters offered little resistance. Brown, four of his sons, and three recruits collected rifles and revolvers and set off for the town. They stopped at a settlement near Pottawatomie Creek where, late in the evening, the party killed five men propelling Brown into infamy. John junior, who wasn’t there, surmised that his father acted to give the enemy shock treatment—“death for death” (Horwitz, 54). While Brown deemed the actions warranted, Horwitz notes, “this widespread violence came at considerable cost to Brown’s family” severely shaking his sons who participated in the murders (Horwitz, 55).

In October of 1856 a weary, sickly Brown left Kansas to gather supporters and much needed resources to continue his crusade. Over the next three years Brown mobilized recruits including a core group of financial backers later known as the Secret Six. Brown’s burgeoning army began formal military training including careful study of guerrilla tactics. Horwitz is careful to document the army’s moves and Brown’s copious planning to demonstrate the depth and detail of his mission. By July 1859, the band was encamped in a small farm outside of Harpers Ferry to finalize their preparations. The party remained much smaller than Brown had anticipated, but he believed more would surely join once events were set into motion. Horwitz vividly captures the men’s last months before they descended on the town. Included in the party was William Thompson, a jovial man, who had left behind a young wife to join Brown; William Leeman, a hardscrabble shoe factory worker from Maine; and Dangerfield Newby, an ex-slave who returned to Virginia to help free his wife and children. Although the men’s motives varied, a mix of ideology and adventure propelled the mostly youthful party. Whatever excitement they exhibited in the months leading up to the raid had dimmed on the evening of the sixteenth as Brown led his men from the farm onto the road to Harpers Ferry. It was later remarked that they all felt “like they were marching to their own funeral” (Horwitz, 129). Horwitz is wildly successful in capturing the men’s characters and recreating their actions during the raid. By so doing, he resurrects a group fundamental to Brown’s mission but largely obscured by their Captain’s long shadow.

When teaching classes in Nineteenth-Century American or Southern history I always try to include a lecture-discussion titled: “The Madness of John Brown?” Most students, familiar with Harpers Ferry at the very least, immediately deem the man with the intense eyes and unruly hair crazy. But, after further discussion and a survey of primary sources, students’ firm stances quiver. Brown’s murky motives and mental state provoke as much disagreement today as on the eve of civil war. Is a moral cause so great as to justify murder? Or, is the killing of another person at any time fundamentally wrong? These were difficult questions that divided Nineteenth-Century Americans as they assessed Brown and the raid’s meaning. Horwitz does well in trying to decipher Brown’s actions, a man who refused to plea the insanity defense (a new but widely accepted doctrine in American law). Horwitz suggests that Brown, fully aware of his actions and perhaps even committed to a suicide mission, used the spoken word to grand avail in the aftermath of Harpers Ferry. Feverishly writing from his jail cell, Brown began a quest for martyrdom unintentionally enhanced by his captors—Brown went so far as to self-consciously emulate Samson. Joined by a cross-section of Americans, though few in number, Brown wasn’t, according to Horwitz, a “charismatic foreigner crusading from half a world away” or “an alienated loner” (Horwitz, 3). Instead, he garnered the approbation of figures such as Henry David Thoreau but also the admiration (for his courage and convictions) and condemnation (for his use of violence) by the likes of Abraham Lincoln.

As a narrative of John Brown’s motives and beliefs, and as an investigation of his family and followers, Midnight Rising is an incredible successful book. As an explanation for how these events connected to, or partly caused the American Civil War Horwitz falls short. The author’s typically sharp focus becomes highly fragmented in his final two chapters, which follow his character’s lives more than the raid’s aftermath and meaning. But I’m not convinced that this undermines the volume given the vast literature on the war’s coming (readers would do well to also investigate David Potter’s The Impending Crisis or Elizabeth Varon’s Disunion! for instance). In the end, Horwitz gives readers a thoughtful, haunting, and sometimes disturbing tale of John Brown’s tragic place in American history.

As a narrative of John Brown’s motives and beliefs, and as an investigation of his family and followers, Midnight Rising is an incredible successful book. As an explanation for how these events connected to, or partly caused the American Civil War Horwitz falls short. The author’s typically sharp focus becomes highly fragmented in his final two chapters, which follow his character’s lives more than the raid’s aftermath and meaning. But I’m not convinced that this undermines the volume given the vast literature on the war’s coming (readers would do well to also investigate David Potter’s The Impending Crisis or Elizabeth Varon’s Disunion! for instance). In the end, Horwitz gives readers a thoughtful, haunting, and sometimes disturbing tale of John Brown’s tragic place in American history.

I agree with you on the review. It was a great book and very illuminating. One other aspect of the crisis I would have liked to see a bit more of were the deliberations that occured in Washington by the Buchanan administration in formulating a response. For example the decision to send the available Marine contingent immediately rather than wait for Regular troops at Fort Monroe. I have become aware of those discussions from other sources and they are a fascinating part of this story. A great review and a very good book. Thank you

Great point, Jim! I think this speaks to the broader context that is missing at the book’s close. Horwitz loses his otherwise tight focus and doesn’t quite connect the dots. Your point about the Buchanan administration’s response is quite interesting and would have certainly created an interpretive framework to posit some important points about the raid’s meaning and legacy. Thanks for the insightful remarks, and I’m glad that you, too, enjoyed the book!

Thanks for the review, Jim. I’ve been looking forward to the chance to read this. I thought “Confederates in the Attic” is one of the most insightful books about the Civil War that’s ever been written just because of Horwitz’s willingness to explore the topic so widely, so when I saw that he was returning to the subject of the war (or at least the immediate pre-war), I was psyched. Your review makes me think the book will definitely live up to my expectations, even if Horwitz didn’t take the same kind of reflective approach he took for “Confederates….”

Small point but still an important one. The first person to die in the raid was Haywood Shepherd, not Hayward Shepherd, a free Black man employed by the B&O Railroad. The late Mr. Horowitz may have gleaned this bit of misinformation from the monument in Harpers Ferry that was erected by the UDC. Fascinating book nonetheless.