James Monroe at War

Part One

Emerging Revolutionary War is honored to welcome guest historian Scott H. Harris, Director of the James Monroe Museum.

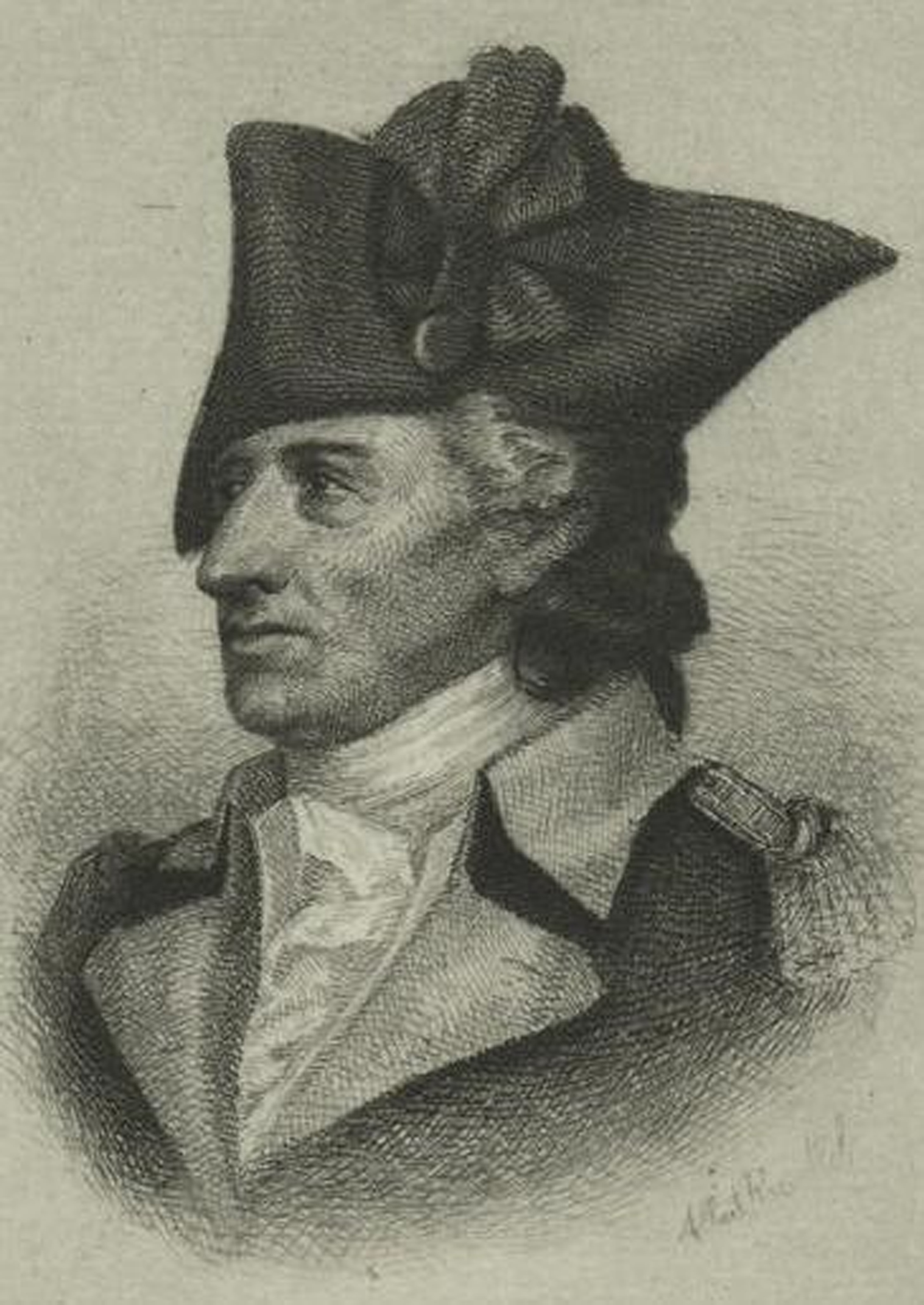

It is one of the great exploits of the American Revolution. On the night of December 25, 1776, General George Washington led the Continental Army across the icy Delaware River to attack a Hessian garrison at Trenton, New Jersey. Young Lieutenant James Monroe held the flag behind Washington as they were rowed across the freezing river (standing up).

Except, that’s not what happened.

Monroe was actually already ashore on the far side of the river with Captain William Washington and a small detachment of men, scouting ahead of the American column. On their way to Trenton, the troops encountered a local physician named John Riker, who agreed to go with them. His presence would prove fortuitous.

During the battle the next morning, as Monroe again joined Captain Washington to lead an attack against a battery of Hessian artillery, he was hit by a musket ball that severed an artery in his left arm. Monroe’s arm and his life were saved by Dr. Riker’s quick action, but the bullet stayed in his body to the end of his days. It was not the only enduring legacy of his wartime service.

During the battle the next morning, as Monroe again joined Captain Washington to lead an attack against a battery of Hessian artillery, he was hit by a musket ball that severed an artery in his left arm. Monroe’s arm and his life were saved by Dr. Riker’s quick action, but the bullet stayed in his body to the end of his days. It was not the only enduring legacy of his wartime service.

The American Revolution was a transformative experience for James Monroe, one that he described in a letter written late in his life:

“Though young at the commencement of our revolution, I took part in it, and its principles have invariably guided me since. Nothing can be more deeply fixed in the judgment and heart of anyone than are the principles of our free system of government in mine.”

Monroe had enrolled at the College of William and Mary in June of 1774. His studies had barely advanced before he, like many of his classmates, got caught up in revolutionary fervor. Monroe was part of a group of students who seized arms from the Governor’s Palace on June 24, 1775. In February of 1776 he was commissioned a lieutenant in the 3rd Virginia Infantry Regiment.

The 3rd Virginia, under the command of Colonel (later Brigadier General) George Weedon of Fredericksburg, joined the Continental Army on Long Island in August, 1776. The following month, the regiment distinguished itself in a skirmish at Harlem Heights. While Monroe and the 3rd Virginia did not fight in the Battle of White Plains on October 28, his company inflicted 56 casualties on a British detachment during a skirmish two days prior.

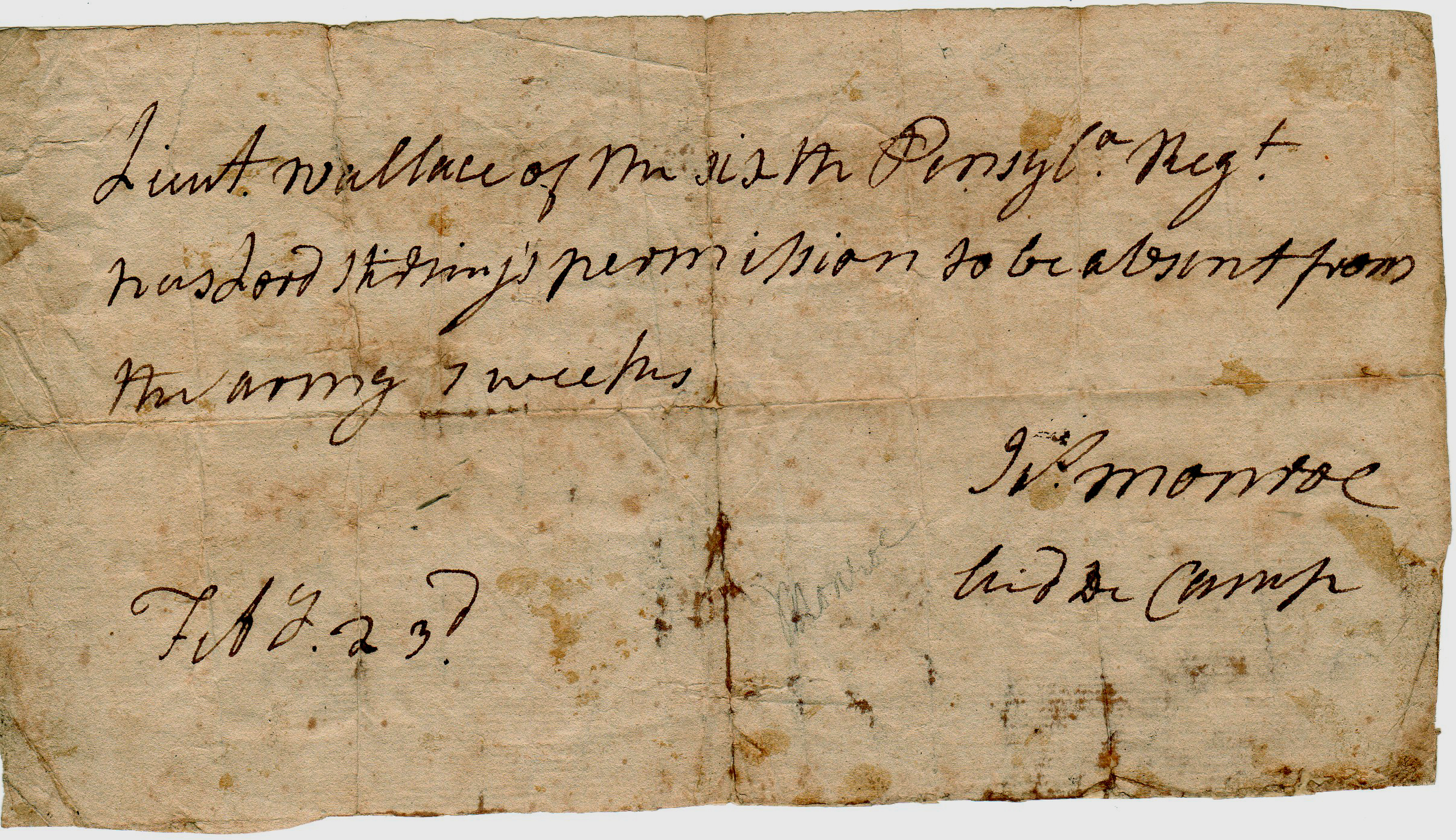

Monroe was promoted to captain in recognition of his service at Trenton, and spent three months recuperating in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Once recovered, he was made a major and became an aide-de-camp to the American general William Alexander (who claimed the British title of Lord Sterling). In this capacity Monroe served with other young men who would figure in his later life and career, including Aaron Burr, Alexander Hamilton, John Marshall (a childhood friend) and the Marquis de Lafayette. During the autumn of 1777, Monroe fought in the battles of Brandywine and Germantown, and later endured the Continental Army’s harsh winter encampment at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777-78.

Leading a scouting party at the Battle of Monmouth in June, 1778, Monroe sent General Washington a dispatch warning of a potential threat to the Continental Army’s right flank:

“Sir–Upon not receiving any answer to my first information and observing the enemy inclining toward your right I thought it advisable to hang as close on them as possible—I am at present within four hundred yrds. of their right—I have only about 70 men who are now fatigued much. I have taken three prisoners—If I had six horsemen I think If I co’d serve you in no other way I sho’d in the course of the night procure good intelligence w’h I wo’d as soon as possible convey you. I am Sir your most ob’t Serv’t Jas. Monroe.”

The warning allowed Washington to counter the British move successfully. Monmouth was the last time Monroe was under fire during the Revolutionary War.

Great to have you with us, Scott. Really enjoyed this piece. Monroe is easily the most overlooked member of the Virginia Dynasty, going all the way back to his service in the Revolution. Why do you think that is?

Partly it was the exhalted company he kept, including his preceding Dynasty colleagues. Also, his two terms were largely free of overt partisanship (the “Era of Good Feelings”) and no major military conflicts. Less drama equals less space in the pantheon, I guess.

Interesting to learn that Monroe is the only president to have a Hessian musket ball in him . Thanks!

I have just become a fan of James Monroe.