Savez Read Invades the North

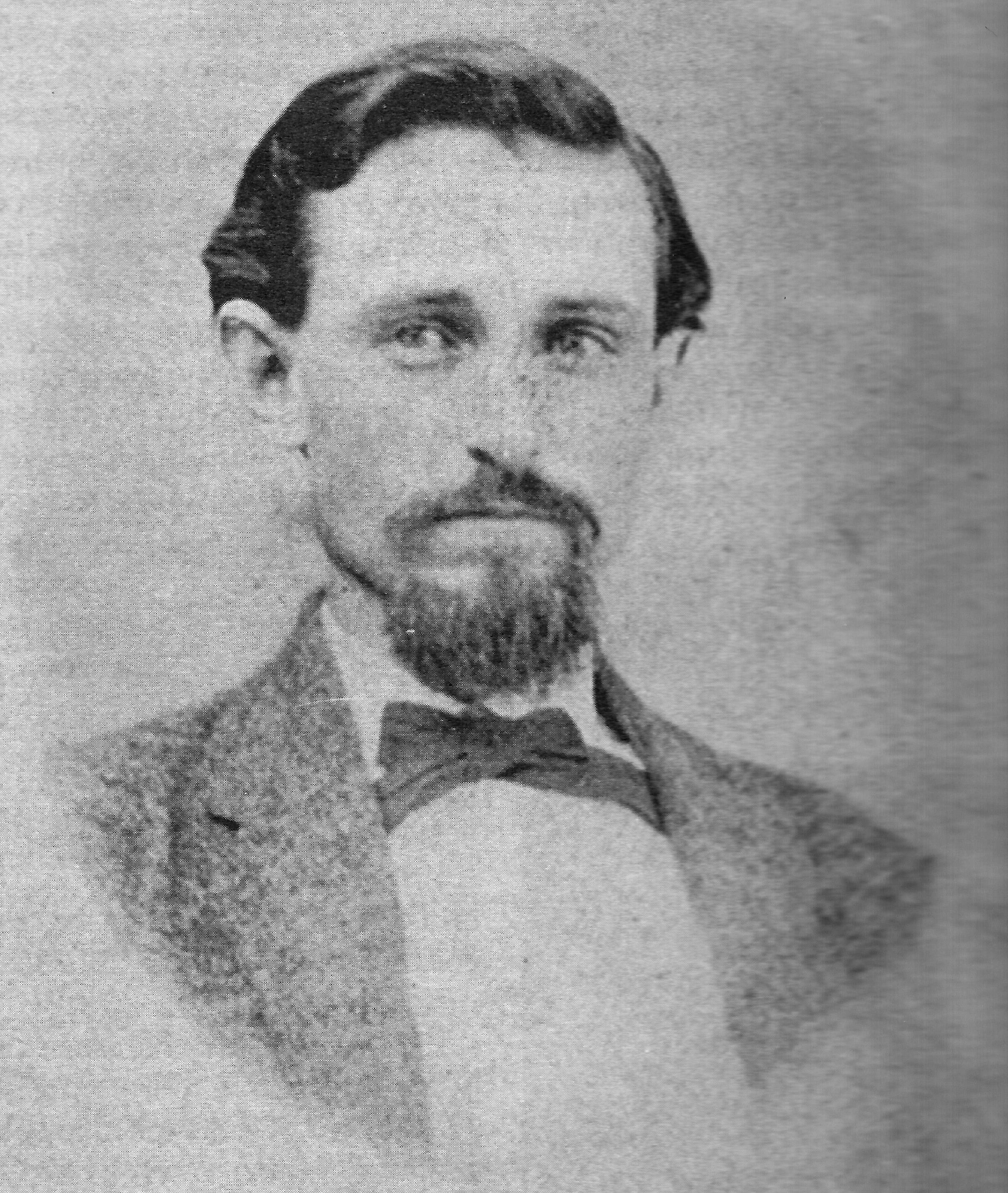

Who? Lieutenant Charles William Read, CSN, seemed an unlikely hero. Of unprepossessing appearance, the Mississippian was short and slight with sharp, angular features adorned by a slender mustache and goatee. He usually confronted the world in a soft-spoken, taciturn manner—until motivated otherwise.

Who? Lieutenant Charles William Read, CSN, seemed an unlikely hero. Of unprepossessing appearance, the Mississippian was short and slight with sharp, angular features adorned by a slender mustache and goatee. He usually confronted the world in a soft-spoken, taciturn manner—until motivated otherwise.

Read had graduated last of twenty-five midshipmen in the Naval Academy class of 1860, earning numerous demerits for fighting, swearing, failure to pass inspection, and other infractions. A classmate (and future Union officer) wrote that Read, “was not considered very brilliant, but was one of those wiry, energetic fellows who would attempt anything but study.” Among difficult academic subjects, he found French incomprehensible. The only word he could pronounce correctly was “savez,” a form of the verb “to know,” which he repeated hundreds of times, even ending sentences with it. For the rest of his life, Read would answer to the nickname “Savez.”[i]

The young officer soon resigned his commission to join the Confederate Navy, apparently mastering the practical skills of seamanship, navigation, and gunnery while earning a notable record under fire. Read was commended for bravery after temporarily assuming command of the paddle-wheel gunboat CSS McRae when the captain was wounded opposing Farragut’s grand assault on New Orleans; he served as executive officer and acting commander of the ironclad CSS Arkansas during her gallant, bloody, but futile battles with the Union river fleet around Vicksburg in summer 1862.

By November, Read reported to the CSS Florida undergoing repairs in Mobile with veteran Lieutenant John Newland Maffitt in command. Maffitt wrote in his journal: “Mr. Read is quiet and slow, and not much of a military officer of the deck, but I think him reliable and sure, though slow.” A few months later, Florida’s captain would write that Read was, “daring beyond the point of martial prudence.” Florida would become a renowned commerce raider second only to Alabama in captures of Union vessels. She boldly escaped Mobile past Union blockaders in January to cruise the coast of South America.[ii]

May 6, 1863 off Cape São Roque, the easternmost shoulder of Brazil: Florida captured the small brig Clarence returning to Baltimore with a cargo of coffee. Read proposed in writing to Maffitt that he take command of Clarence as a new raider with twenty crewmen and, “proceed to Hampton Roads and cut out a gunboat or steamer of the enemy.” With the non-descript brig’s legitimate commercial papers, he should have no problem passing Fortress Monroe inside the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay. Once there, Read said he would be prepared, “to avail myself of any circumstances which might present for gaining the deck of an enemy’s vessel.” Lacking that opportunity, he would proceed to Baltimore to “fire the shipping” there.[iii]

Maffitt enthusiastically endorsed the plan and wished Read God’s speed: “You’ll be on your own, no orders to hamper you. Your success will depend on yourself and your sturdy heart.” A 6-pounder boat howitzer with ammunition was provided as the brig’s only armament. Read proceeded north, approaching the Chesapeake, but learned from captured merchantmen that Union warships were closely investigating all vessels entering the bay. He sailed on by and proceeded for all of June 1863 to terrorize the entire northeastern seaboard, delivering welcome tidings to his people absorbing losses at Gettysburg and Vicksburg.[iv]

Read augmented the little howitzer with spare wooden spars painted black and mounted on wooden carriages—Quaker guns. He even had his sailors practice the motions of loading and running out the “guns.” Presented with this impressive broadside, one Yankee captain jumped to his cabin roof and bellowed through a trumpet, “For God’s sake don’t shoot! I surrender!” On another occasion, they spotted a potential prey that was too fast catch, so Read raised the American flag upside down as the international sign of distress and lured in the coastal trading bark Tacony. The new prize proved to be a much better sailer, so Read transferred flag, crew, and “armament” into her and burned Clarence.

One captured vessel carried twenty lady passengers on the way to Mexico; Read bonded her for $7,000, loaded fifty “guests” from previous prizes, and set her free. Knowing that word of his activities would spread the moment former prisoners reached the nearest port, Read boasted privately to the Yankee captain that a great fleet of Southern ships would soon strike the Atlantic coast. The U.S. Navy would be scrambling after bigger threats than little Tacony.

Navy Secretary Welles and the rest of the country soon got word as fearful tales of fire and piracy, real and imagined, filled the headlines. The phantom fleet grew to include the hated Alabama and Florida, both of which were nowhere near. Within a few days, thirty-eight vessels of every description, from warships to hastily-armed merchantmen, fanned out in every direction without organization, planning, or good idea of where to look or what to look for. Read did encounter a couple of them, but stuffing prisoners in the hold and flying the American flag, he bluffed his way through and sent them racing off after ghosts.

The huge packet Isaac Webb carried 750 European immigrants on their way to new homes in America. Read had just set torch to a nearby fishing schooner when he stopped and boarded Webb. Viewing the schooners fate, panicked passengers dropped to their knees and raised their voices to heaven before being assured that their ship would be released under $40,000 bond. He also was compelled to bond ($150,000) and release the big clipper Shatemuc with hundreds of Irish immigrants, despite her tempting cargo of iron plate and war supplies. The fine new clipper Byzantium, Newcastle to New York with a load of coal, was not so lucky and went up in flames.

New England fishing schooners dotted the sea in every direction, hunting for shoals of cod and halibut. Two days later, there were six fewer of them. From recent newspapers, Read learned that the navy now had an accurate description of his ship, so he took another mackerel schooner, the 90-ton Archer, shifted into her and burned Tacony. “No Yankee gunboat would ever dream of suspecting us,” he noted in his diary. Three cheers and a ration of grog accompanied the raising of the flag on a new Confederate man-of-war. But he was out of ammunition for the howitzer.[v]

By morning June 26, 1863, Archer lay off the coast near Portland, Maine, about as far north in Yankeedom as one could go. Read kidnapped two local lobstermen from their adrift dory and learned from them the situation in the harbor where two vessels lay: the schooner-rigged U.S. revenue cutter Caleb Cushing mounting a 12- and 32-pounder, and the fast steam passenger liner Chesapeake, ready to sail for New York in the morning. Read plotted to capture Chesapeake, burn remaining shipping, and dash to sea.

Guided by the helpful lobstermen, Archer glided into harbor as the sun set. Read gathered his men. But his only engineer doubted he could get steam up, operate Chesapeake’s engines, and make it out under the guns of the fort before morning. So Read changed his plans, rowed silently up to Caleb Cushing, overwhelmed the drowsing deck watch, and captured the rest in their hammocks. The officer in charge, a youthful Lieutenant Davenport, was an Annapolis classmate and friend.

Just then the wind dropped, so they towed Cushing out with row boats, caught an offshore breeze, and by full daylight were five miles away. Portland awoke to stunning news that their revenue cutter had mysteriously disappeared, some assuming that the Southern-borne Davenport had turned traitor.

Chaos ensued as the port collector, without permission or orders, hustled a few Regulars from Fort Preble aboard sidewheeler Forest City with two 12-pounder howitzers and set off in chase. Meanwhile, the mayor pressed Chesapeake into service with a detachment of the 7th Maine Volunteers, a clutch of zealous citizens armed with squirrel rifles, ancient muskets, and rusty cutlasses, and a makeshift battery of two 6-pounder field guns. In their wake, a host of curious spectators jumped on an unarmed tug and anything else that could float.

The steamers caught up with slowly sailing Cushing; a few rounds flew in all directions with some close misses but no hits. Out of ammunition and as a final gesture of defiance, Read and his men set Cushing ablaze and piled into boats before being surrounded and captured. They had taken twenty-two prizes in twenty-one days. It was one of the most astounding episodes of the naval war.

After release, Read continued his daring exploits at the Battle of Trent’s Reach on the James River below Richmond, January 1865, and later commanded the CSS Webb at Shreveport, Louisiana. On April 22, he tried to break out of the Mississippi and escape, but was forced to ground and set Webb afire before being once more captured. After the war, Read served with Cuban rebels trying to overthrow Spanish rule. Following a long career as a merchant captain, Charles “Savez” Read died on January 25, 1890, and is buried at Meridian, Mississippi.

[i] David W. Shaw, Sea Wolf of the Confederacy: The Daring Civil War Raids of Naval Lt. Charles W. Read (New York: Free Press, 2004), 6.

[ii] Chester G. Hearn, Gray Raiders of the Sea: How Eight Confederate Warships Destroyed the Union’s High Seas Commerce (Camden, Maine: International Marine Publishing), 83.

[iii] Shaw, Sea Wolf of the Confederacy, 74.

[iv] Hearn, Gray Raiders of the Sea, 84.

[v] Hearn, Gray Raiders of the Sea, 89.

Thrilling “Read.”