“A remarkable military position” The Battle of Cockpit Point and the Potomac Blockade

On October 16, 1861 pro-Unionist Lewis McKenzie of Alexandria sent US Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles a report on the newly constructed Confederate batteries along the Potomac River. McKenzie called the batteries at Cockpit Point “a remarkable military position. It commands Freestone Point on the north and Shipping Point on the south, being distant from either about 2 ½ miles. The land is higher than either of them and it projects farther into the Potomac.” Though McKenzie was relating an official military opinion, as a civilian even he was aware of this important point along the Potomac River.[i]

On October 16, 1861 pro-Unionist Lewis McKenzie of Alexandria sent US Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles a report on the newly constructed Confederate batteries along the Potomac River. McKenzie called the batteries at Cockpit Point “a remarkable military position. It commands Freestone Point on the north and Shipping Point on the south, being distant from either about 2 ½ miles. The land is higher than either of them and it projects farther into the Potomac.” Though McKenzie was relating an official military opinion, as a civilian even he was aware of this important point along the Potomac River.[i]

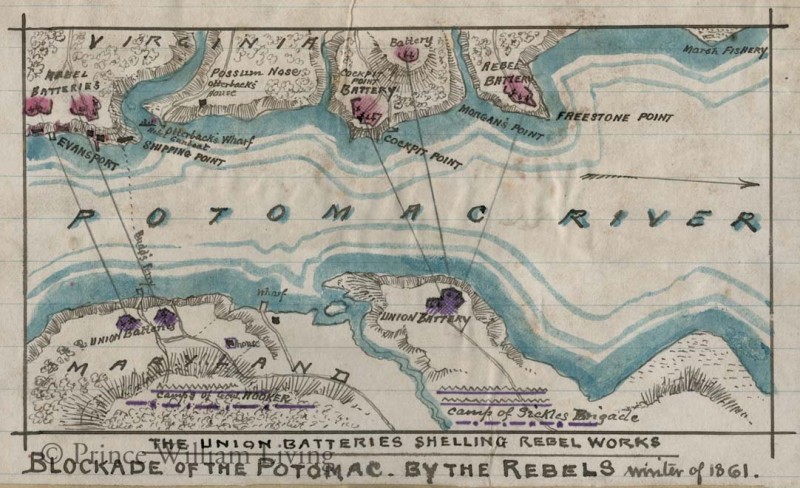

Beginning in May 1861, Virginia and then Confederate forces pondered how best to defend the Potomac River. An established Navy wasa strong advantage for the Federals because it could run freely up and down the navigable Potomac. In the fall of 1861, with no large Federal military presence outside of the outskirts of Washington, D.C., Confederate officials determined to establish a series of batteries along the Potomac in Prince William and Stafford Counties. These batteries would support trade between the pro-southern population in Maryland and Virginia, as well as hinder commercial shipping to Washington. The river was a crucial link for the city, as only one spur line of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad served Washington. The city depended on the river as its connection to the outside world.

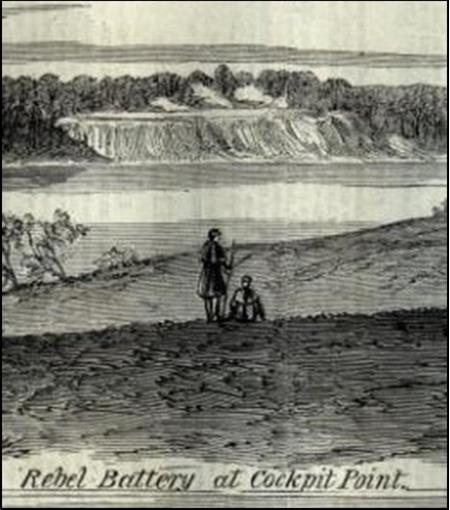

Many considered the Confederate gun battery at Cockpit Point to be the most dangerous threat to northern shipping (the gun batteries are actually on Possum Nose, as the point was a lower geographical feature near the batteries, though Cockpit Point was used by both sides to name the battery position). The Confederates built the battery in secret leaving all the trees in front of the battery standing. The most likely designer of the batteries was the irascible Isaac Trimble, who oversaw construction of most of the batteries along the river in Prince William County. By October 18th, the battery was completed and the trees were quickly cut down to open fire on a passing ship convoy.[ii]

Though the batteries were constructed under the auspices of the Confederate Navy, the men manning the guns were infantry. Various units moved in and out of the area to man the guns, and their skill as gunners was obvious, as they rarely were able to hit anything that fired along the river. Hooker wrote the batteries “fire wretchedly” and he was, “forced to the conclusion that the rebel batteries in this vicinity should not be a terror to anyone.”[iii] Most of the men manning and protecting the guns were part of Louis T. Wigfall’s “Texas Brigade.” Later that winter, these men would be under the leadership of the famed John Bell Hood. The Texans along with Alabamians and Tennesseans did their best to make good work of the guns, but typically with little success.

Whether the guns at Cockpit Point were effective or not did not matter to the US Navy. The safety of commercial traffic on the Potomac could not be guaranteed so the US Navy officially declared the river “closed” on October 15th. The Navy did not prohibit commercial traffic, as many ships did run the gauntlet of the batteries, but the Navy could no longer guarantee the safety of private ships.[iv]

As the impact of the blockade began to damage not only the Federal City economically but also embarrass the Lincoln administration, Gideon Welles urged his Navy to do something about the batteries. Though the Navy argued that it would take a joint expedition with the Army to silence the guns, they attempted to test the strength of the Cockpit Point batteries. Lt. Wyman, commanding the Potomac Flotilla decided that the Confederate batteries at Cockpit Point/Possum Nose might be vulnerable from enfilading fire to the north. To test his theory and to gain a “more complete knowledge” of the strong batteries there, Wyman ordered the Anacostia and the USS Yankee to sail within range of Confederate batteries and engage them in the front and to their north flank. Wyman believed the batteries could fire down river and across the river, but not upriver.[v]

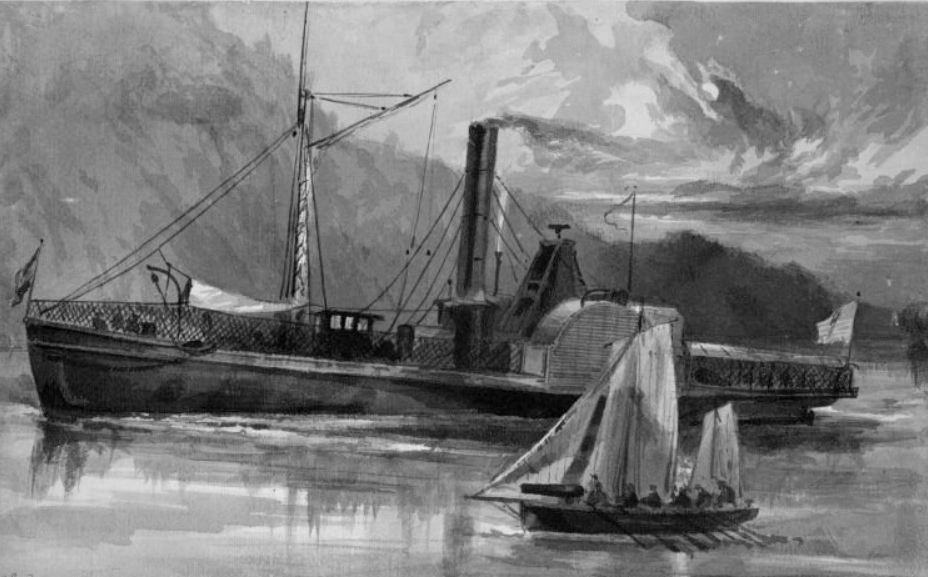

On January 3, 1862, Wyman ordered Lt. Thomas Eastman to take the Yankee (a 146 feet long side wheel steamer) and oppose the batteries directly from the east while the smaller Anacostia (a 129 feet long screw steamer) positioned north of the batteries to enfilade the Confederate position. Around 10am, the Anacostia opened up with its two 9-inch Dalhgren guns. Soon after the Yankee opened up with her five guns. In the short fight, the Confederates abandoned one of their batteries and had one of their large guns dismounted. The Yankee suffered a hole in its port bow, but the damage was not severe.[vi]

Wyman reported after the short battle that the Confederate fire was inaccurate and the batteries were susceptible to enfilading fire from the north. With their mission accomplished, the Federal ships disengaged. Wyman also reported that soon the Confederates repaired the damages, remounted their guns and built a new earthwork to protect the batteries from enfilading fire from the north. The short battle accomplished little and only alerted the Confederates to a weakness in their defenses.[vii]

Though the Confederate blockade of the Potomac River would continue until March 1862, the batteries at Cockpit Point saw little action. Shell were occasionally fired into Maryland and at passing commercial ships but, the battery’s reputation was more damaging than its actual ability to inflict harm. Though Lincoln pushed to have the blockade lifted, the Navy could not do it alone and McClellan refused to make the effort, finding it of little consequence to the overall strategy of the war. Soon the Confederates lifted the blockade themselves as Johnston ordered all the Confederates in northern Virginia to evacuate and move towards Fredericksburg on March 8, 1862. Though little is covered in today’s history books, the Potomac Blockade stands as one of the few times the Confederates were able to directly impact the economic and military situation in Washington, D.C. It also proved to be an international embarrassment for Lincoln and sowed the seeds of discontent between McClellan and the President.

Be sure to check out the January 2017 edition of the Blue and Gray Magazine featuring the article: “The Potomac Will Be Effectively Closed” – War on the Potomac, May 1861-March 1862 by Rob Orrison and Bill Backus. The article covers the Potomac Blockade in more detail and includes a driving tour of associated sites.

Preservation Update:

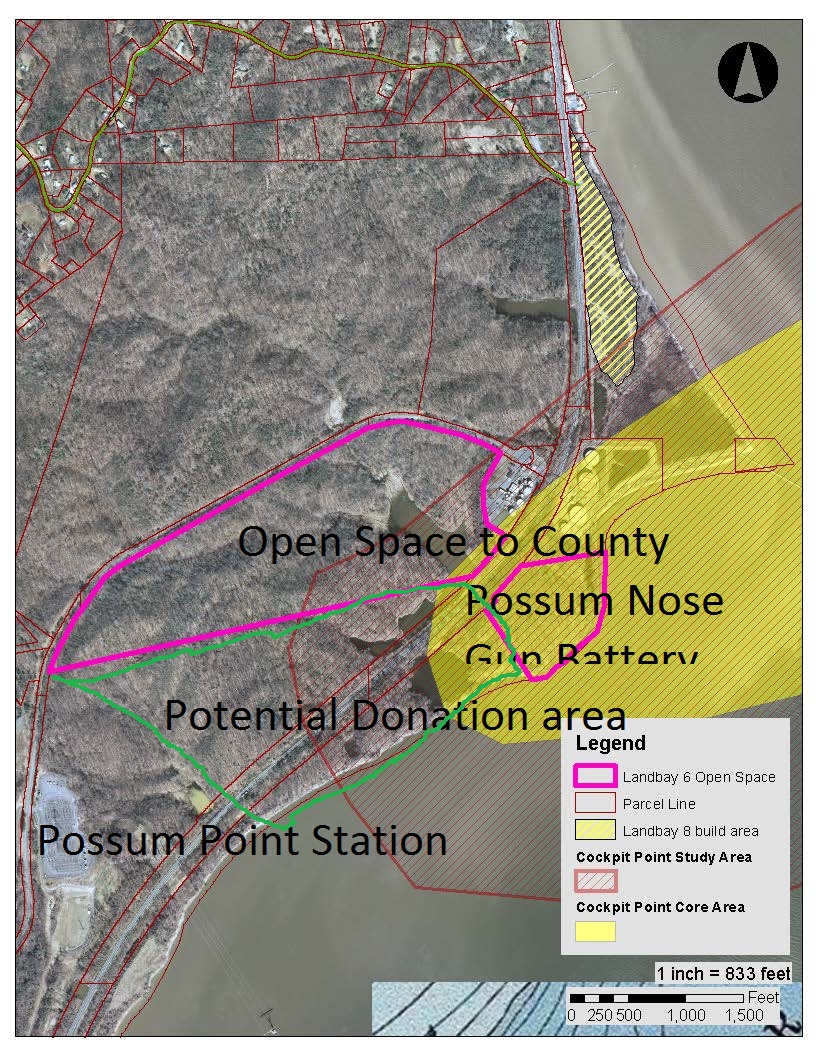

Recently, Prince William County acquired 138 acres of preserved property along the

Potomac River which contains the Cockpit Point/Possum Nose gun batteries. This site is not yet open to the public, but a Civil War Trails marker dedication and special tours of the site will be offered on March 11, 2017. Also, special Boat Tours of the Potomac River covering the Potomac Blockade are offered regularly in the spring and fall. For more information, visit www.pwcgov.org/history or call the Prince William County Historic Preservation Division at 703-792-4754.

[i] ORN Series 1, Vol 4., p. 737.

[ii] ORN Series 1, Vol 4, p. 726.

[iii] OR Series 1, Vol 5, p. 648-649.

[iv] ORN Series 1, Vol.4, p. 718.

[v] ORN Series I, Vol. 5, 15.

[vi] Warren H. Cudworth, History of the First Regiment (Boston, MA: Walker, Fuller, and Company, 1866), 118.

[vii] ORN, Series I, Vol. 5, 15.