The Evolution of Cavalry Tactics: How Technology Drove Change (Part Four)

(part four in a series)

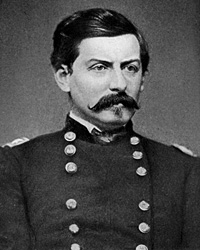

During the early days of the Civil War, Dennis Hart Mahan’s teachings were implemented by the Union high command in particular. Gen. Winfield Scott vigorously resisted the incorporation of volunteer cavalry regiments into the Union armies, as he believed them to be unduly expensive as well as impractical because they would take too long to be trained and made into effective units. Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, who succeeded Scott, believed that it required two years to adequately train volunteer cavalry, and few in 1861 expected that the Rebellion would last that long. Consequently, the Federal high command vigorously debated the question of how to properly use and arm the many volunteer cavalry regiments raised after the defeat at Bull Run.

McClellan was biased against volunteer cavalry, and believed in late 1861 that “for all present duty of cavalry in the upper Potomac volunteers will suffice as they will have nothing to do but carry messages & act as videttes.” A week later, McClellan requested that no more volunteer cavalry regiments be raised throughout the North, since their role was unclear, and questions remained about the army’s ability to mount and arm the new recruits.

The irony was that McClellan spent much of the Crimean War observing cavalry operations, and he had designed the standard-issue saddle for the U.S. Army’s mounted arm. He should have been good at managing cavalry, but he was not. The Army of the Potomac’s mounted arm paid for that.

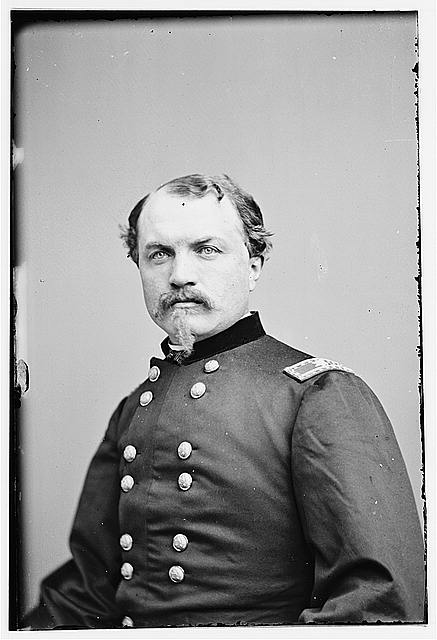

The traditional role of saddle soldiers was well defined, even if McClellan did not make good use of them. “Reliable information of the enemy’s position or movements, which is absolutely necessary to the commander of an army to successfully conduct a campaign, must be largely furnished by the cavalry,” wrote Brig. Gen. William Woods Averell, a West Point graduate, in defining the traditional role of cavalry in the conventional doctrine taught at the Military Academy and as practiced at the beginning of the war. “The duty of the cavalry when an engagement is imminent is specially imperative—to keep in touch with the enemy and observe and carefully note, with time of day or night, every slightest indication and report it promptly to the commander of the army. On the march, cavalry forms in advance, flank and rear guards and supplies escorts, couriers and guides. Cavalry should extend well away from the main body on the march like antennae to mask its movements and to discover any movement of the enemy.”

Averell continued, “Cavalry should never hug the army on the march, especially in a thickly wooded country, because the horses being restricted to the roads, the slightest obstacle in advance is liable to cause a blockade against the march of infantry.” Moreover, “in camp it furnishes outposts, vedettes and scouts. In battle it attacks the enemy’s flanks and rear, and above all other duties in battle, it secures the fruits of victory by vigorous and unrelenting pursuit. In defeat it screens the withdrawal of the army and by its fortitude and activity baffles the enemy.” Averell concluded, “In addition to these active military duties of the cavalry, it receives flags of truce, interrogates spies, deserters and prisoners, makes and improves topographical maps, destroys and builds bridges, obstructs and opens communications, and obtains or destroys forage and supplies.” Although these functions were well defined, McClellan did not use his saddle soldiers for all of them, meaning that the cavalry was not used as effectively as it might have been.

On the Peninsula, McClellan parsed out his volunteer cavalry regiments to specific infantry brigades, primarily using the horsemen as messengers and orderlies. This was a poor use for an expensive arm of the service like cavalry. The government invested millions of dollars into raising and equipping its mounted units, and McClellan frittered them away. However, McClellan wisely formed the Cavalry Reserve, consisting of most of the Regular Army mounted units. “As to the regular Cavalry,” wrote McClellan, “I have directed all of it to be concentrated in one mass that the numbers in each company may be increased & that I may have a reliable and efficient body on which to depend in a battle.” McClellan relied heavily on the Cavalry Reserve during the Peninsula Campaign. His Regulars captured the first Confederate flag taken in combat, and they made a magnificent but disastrous charge into Southern infantry at Gaines Mill, saving the V Corps from destruction. The Regulars performed well, foreshadowing better days to come for the Northern horsemen.

And then came Jeb Stuart’s First Ride Around McClellan. The spectacle of Stuart’s escape overshadowed the solid service of the Regulars. Further, Brig. Gen. Philip St. George Cooke—Stuart’s father-in-law and the commander of McClellan’s cavalry in the field—proved himself not to be up to the task of pursuing his son-in-law, and Cooke, greatly embarrassed, soon found himself banished to Minnesota. He never commanded troops in the field again.

Eric: Excellent material as always. I’d note that before leaving for the Land of Ten Thousand Lakes, Cooke ordered the controversial charge of the 5th U.S. at Gaines’ Mill, providing an opportunity for McClellan’s acolyte Fitz John Porter to engage in the blame game.

John, stand by. That episode will be addressed in part five…

That sounds good. The analysis of McClellan’s failure to “get it” regarding the proper use of cavalry was enlightening. That seems to have reared its ugly head again during and after the Antietam Campaign when Stuart pulled off something along the lines of “The Ride: The Sequel”. Will you be dealing with that at all?

Its seems in the military history of cavalry that cavalry often never kept to the dicta Averell wrote about. Cavalry leaders in the Civil War struggled with it and the German use of cavalry in their attack on Belgium and France in 1914 failed to keep to this role. The Germans ultimately used their cavalry as dismounted infantry to fill in gaps in their lines, but before that they often just may headlong charges into infantry units. They accomplished very little screening and scouting, from what I’ve read.

Also… wasn’t the leading Cavalry man in the antebellum U.S. army Philip S.G. Cooke? Didn’t he write a book on the use of cavalry which was anathema to Averall’s dicta?