The Evolution of Cavalry Tactic: How Technology Drove Change (Part Eight)

(conclusion to a series)

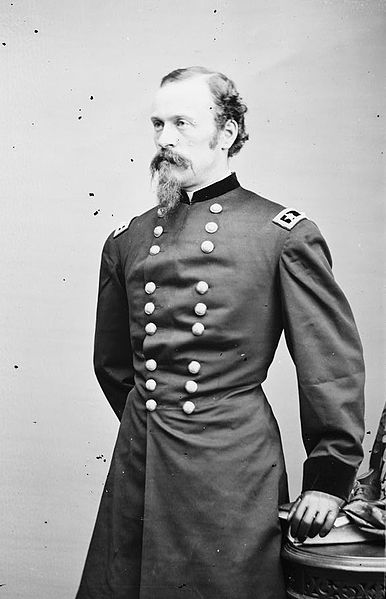

Young Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson, a member of the West Point class of 1861 who was known as Harry to his family and friends, commanded the Cavalry Corps of the Military Division of the Mississippi, in 1865. Wilson’s Corps consisted of roughly 13,500 troopers organized into three divisions, commanded by Brig. Gens. Edward M. McCook, Eli Long, and Emory Upton. Each trooper carried seven-shot Spencer carbines, meaning that this was the largest, best armed, best mounted force of cavalry ever seen on the North American continent to date. Capable of laying down a vast amount of rapid and effective firepower, Wilson’s Corps proved to be a juggernaut. In short, Wilson commanded a mounted army that could move from place to place quickly and efficiently and was capable of laying down a previously inconceivable amount of concentrated firepower.

On March 22, 1865, Wilson’s mounted army began a lengthy raid through Alabama intended to eviscerate what remained of the Confederate Deep South, all while operations around Petersburg, Virginia moved toward their climax, and on the day after Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s ultimate battlefield victory at Bentonville in North Carolina. Wilson’s mounted army was to deliver the coup de grace to a dying Confederacy.

While one column of his command headed for Tuscaloosa, Wilson’s main column headed for Selma. After routing Forrest on March 31, Forrest made a fighting retreat to occupy unfinished works surrounding the town of Selma. On April 2, his troopers overwhelmed and routed Lt. Gen. Nathan B. Forrest’s greatly outnumbered cavalry corps in ferocious fighting that featured a saber charge of the 4th U.S. Cavalry led by Wilson himself that routed the Southerners. General Long was wounded in the head during the fierce fighting, and Forrest was wounded in combat, too, as his small corps was largely wrecked.

On April 4, part of Wilson’s command chased Confederate troops out of Tuscaloosa and burned the campus of the University of Alabama’s campus there, preventing another division from reinforcing Forrest in time for the Battle of Selma. Wilson occupied the former Confederate capital of Montgomery on April 12, after the surrender of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House. Wilson planned to head east into Georgia to destroy remaining arsenals and stocks of ammunition there, and to disperse any remaining Confederate forces. A 3,700-man detachment under Col. Oscar H. La Grange fought the Battle of West Point on Easter Sunday, April 16, 1865, overwhelming a scratch force of Confederate old men and young boys commanded by Brig. Gen. Robert C. Tyler. Tyler was mortally wounded by a sharpshooter, the last general officer to be killed in the Civil War.

While La Grange was fighting at West Point, Upton’s division defeated Confederate forces at Columbus, Georgia, capturing the city and its naval works, burning the incomplete CSS Jackson in what is often called the last battle of the Civil War. On April 20, Wilson’s command ended its raid with the capture of Macon, Georgia. Six days later, Gen. Joseph E. Johnston surrendered all remaining Confederate troops in the field east of the Mississippi River to Sherman at Bennett Place, near Durham, North Carolina. Elements of Wilson’s command then captured Confederate President Jefferson Davis as he attempted to escape to Mexico.

In the meantime, in the days immediately after the 1863 Battle of Gettysburg, the Union high command created the Cavalry Bureau as a means of providing remounts to cavalry forces operating in the field. Various remount camps were established in the field near the areas where the main armies were operating so that remounts were readily available to any man who lost his mount while on campaign. While the drain on horseflesh was incredible, the Cavalry Bureau did a creditable job of making certain that the blue-clad horse soldiers had a ready supply of remounts that enabled it to remain an effective force that maintained its efficiency in spite of rampant corruption that plagued the acquisition of horses. The Cavalry Bureau ensured that the Union cavalry would remain in the field at all times from the time of its formation during the summer and fall of 1863. The importance of its role cannot be understated.

And with that, the evolution of the Union cavalry in the Civil War was complete. From its humble beginnings as widely dispersed detachments of orderlies and messengers, Wilson’s Corps now served as a prototype for the highly mobile armored tactics of the Twentieth Century: men used their horses to move from place to place, usually fought dismounted in order to bring to bear the force multiplying effect of their repeating carbines, and served as a strike force. The days of the climactic, dramatic, grand Napoleonic cavalry charge were over. So, too, for the most part, were the days when the primary role of the cavalry was scouting, screening, and reconnaissance, although those roles remain important to the present day. By its evolution over the course of the Civil War, the cavalry became a fearsome offensive mobile strike force that could and did make deep incursions into enemy territory, drawing off the enemy cavalry so that infantry and logistical columns could act largely unmolested as they made their way across the South. Nowhere was this more evident than during Sherman’s Carolinas Campaign of 1865, where Bvt. Maj. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick’s command drew off the still-feisty Confederate cavalry and kept it away from Sherman’s army for most of the campaign.

The advances in technology forever altered the role and tactics of the U.S. Army’s cavalry forces. Advances in carbine and artillery technology caused the evolution of cavalry tactics. By the end of the Civil War, very little cavalry fighting was done while mounted; the vast majority of cavalry combat was done dismounted in order to bring to bear the force multiplying effects of the repeating carbines of the Union troopers. While there were a few notable mounted charges and some memorable mounted combat after the Battle of Gettysburg, for the most part, the days of romantic hand-to-hand mounted combat were over. Virtually all cavalrymen were trained as dragoons by then, so that they could fight effectively mounted or dismounted. Eventually, their role came to resemble mounted infantry more than anything else even though they continued to carry traditional cavalry weapons. This evolution probably came just in time; traditional light cavalry tactics involving hand-to-hand combat would have been a miserable failure during the long years of combat with the Native Americans of the West in the decades after the Civil War.

And with that, our study of the effect of technological advances on cavalry tactics during the Civil War comes to an end. If I have done my job properly, you will now have a greater appreciation of those tactics and how technology drove change.

Eric: You have done your job properly, as always. Thanks – and a question. I’m not sure you’ve had a chance to evaluate the evolution of cavalry tactics by the end of the ACW and its influence/lack of same at the beginning of World War I. From what I know it seems to me that the British, at least, used cavalry in its “traditional” role and not in the role exemplified by Wilson’s 1865 mission as a highly mobile deep strike force which would fight largely dismounted. So we have, as a result, events such as the cavalry charge at Mons, which quickly showed that this traditional role was obsolete. Your thoughts would be appreciated, including why lessons apparently had to be “re-learned” the hard way.

John, to be honest, I haven’t ever considered it, but it sounds like an interesting exercise.

That said, it’s given that generals always fight the last war, and the British apparently needed to learn the lessons we have examined here.

This ha been a marvelous series. Thank you for your incite. Why if Wilson’s corps was the prototype did the government go backwards and arm cavalry with trap door Springfields during the plains wars?

It all had to do with saving money. Non-repeating weapons used less ammunition.