BOOK REVIEW – Crossing the Deadlines: Civil War Prisons Reconsidered

I have long believed that Civil War prisoner of war facilities were the final frontier in Civil War scholarship. Under-explored and under-appreciated, it has only been relatively recently that POW camps began to be researched and monographs written.

I have long believed that Civil War prisoner of war facilities were the final frontier in Civil War scholarship. Under-explored and under-appreciated, it has only been relatively recently that POW camps began to be researched and monographs written.

A recent excellent addition to this discourse is Crossing the Deadlines: Civil War Prisons Reconsidered (Kent State University Press, 2018), edited by Michael P. Gray. Author of The Business of Captivity: Elmira and it’s Civil War Prison, Gray has become one of the leading voices in this dark corner of Civil War history.

This interesting tome is a collection of essays from a distinguished group of scholars, with nine entries running the gamit from environment to religion and even dark tourism. It is a compilation that would make William Hesseltine, the late pioneer of prison scholarship, proud.

In his essay, “Civil War Captives and a Captivated Home Front,” Gray opens with the observation that when it comes to Civil War POW camps Andersonville takes up all the oxygen in the room. Of course, it is the death rate – which approached 30% – which has riveted attention on the Georgia pen. Gray argues, “Given the varied nature of Civil War prisons, scholarship must not be limited to just studying death figures, no matter how significant; rather, it should advance to more innovative, eclectic, and profitable methodologies so the truest narrative of Civil War incarceration might be achieved.”

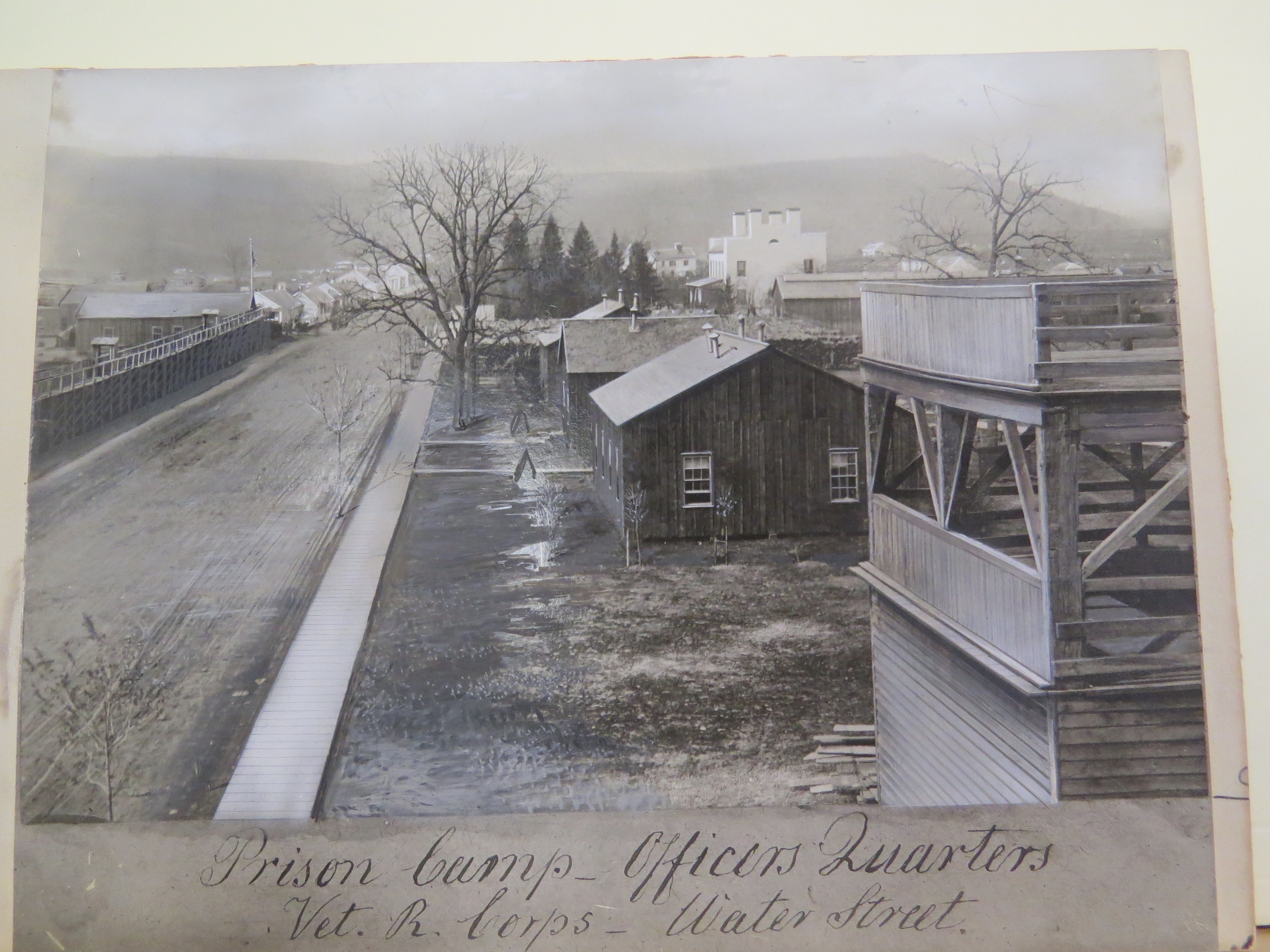

True to his word, Gray delivers the eclectic – a look at dark tourism during the war. In this excellent essay we learn of Victorian ladies ascending sentry ladders to get a look at the Rebel vermin incarcerated at Andersonville, tour boats on Lake Erie which advertised that guests could “see the rebel quarters if not the rebels themselves”, and observation towers built by enterprising men to look over the stockade walls at Camp Douglas and in Elmira for “just ten cents, children half price.”

Lorien Foote contributes a compelling essay about an unpleasant subject entitled “The Sternest Feature of War: Prisoners of War and the Practice of Retaliation.” More prevalent than supposed, “acts of retaliation using prisoners of war were common components of military campaigns and of policy negotiations between Union and Confederate officials.” Indeed, the practice was even codified in military law. “General Orders No. 100, issued on April 24, 1863. Article 27 proclaimed that “civilized nations acknowledge retaliation as the sternest feature of war.”

At the center of the practice of retaliation was conceptions of what civilized warfare meant. This had special significance when it came to keeping prisoners of war. Foote points out that “Because Union and Confederate officials agreed that those who did not conform to the standards of civilized warfare were not entitled to be treated as prisoners of war if captured, struggles over policy and conduct…inevitably spilled over into decisions about the status of captured prisoners.”

One of my favorite scholars of this genre is Benjamin G. Cloyd. A professor of history at Hinds Community College in Mississippi, Cloyd is the author of the path-breaking book Haunted by Atrocity: Civil War Prisons in American Memory. In keeping with this line of inquiry, professor Cloyd’s addition to the volume under consideration here is “Civil War Prisons, Memory and the Problem of Reconciliation.”

In his essay Cloyd suggests that the impulse toward reconciliation is a natural part of human nature, “The potential for forgiveness and restoration assigns purpose to the struggle to find meaning in profound suffering.” However, there are limits. In remembering the Civil War, there has been a strong tendency towards Americanizing the struggle – as is evident with the lingering influence of the Lost Cause mythology. “But as the subject of Civil War prisons in particular shows, reconciliation can also be an illusion,” Cloyd argues.

According to Cloyd “the ideal of reconciliation has harmed as much as it has healed over the years.” This inclination to push the healing became especially a concern after the centennial of the Civil War in 1961-1965, when plans for a national observation collapsed over racial concerns. This, among other things, has led Cloyd to wonder if reconciliation is really possible. “There is more than a whiff of arrogance to our premature expectations of reconciliation,” he observed, “The past evils that created the Civil War continue to endure: do we have the patience and humilty to face this uncomfortable reality?”

Perhaps as much philosopher as a historian, Cloyd’s though provoking essay is worth the price of the book alone. This and his book Haunted by Atrocity make for mandatory reading for all those interested in Civil War studies – and perhaps the human condition in general.

All told, this outstanding volume is a great read and engaging exploration of a field of Civil War study too often neglected. It will have an honored place on my bookshelf, within easy reach.

With historians focused on understanding and explaining the thousands of battles and skirmishes that occurred 1861 – 1865, it was long overdue that some would appreciate the Civil War acting as proving ground for conflict’s after-effects: Letterman’s ambulances, Surgeon General Hammond’s improvements in patient care, Clara Barton’s Missing Soldier Bureau, Andersonville. Meg Groeling provides an exceptional introduction to these side effects in her ECW publication, “The Aftermath of Battle.” And no doubt “Crossing the Deadlines” contributes even more to that understanding (because prisoner care and POW status are topics with which we are still coming to grips.)

The Victor does write history and Andersonville is all we heard about till recently. Capt. Wire was the only one hung for war crimes at Andersonville while his counterparts in the North got off Scot free. Looking forward to reading an open persective that brings to light all of the atrocities to POWs.

At Ft Delaware, POWS were chained outside the Ft at low tide and drowned when the tide came up.

Robt

Having an interest in ft delaware i never heard of that. What was your source of informations please thank you

What a fine essay about a topic that obviously engages your interest.

I have had for decades a sort of guilty fascination with Andersonville. Because I live in New York, I have long been aware of and interested in Elmira, especially the recent scholarship and the efforts of local advocates to recreate at least some of the buildings and other structures on the site. (It’s probably not an accident that the structures at Elmira, like Andersonville, were destroyed almost immediately after those prison camps were emptied). Camp Douglas in Chicago was interesting (though there is almost nothing left of it) when I was a student in that city. It was the place of imprisonment of the “Harpers Valley Cowards,” the unfortunates captured by Stonewall Jackson’s men in the prelude to Antietam. Some of those men were recruited in the city where I live. So I have long been intrigued by the prison camps.

I never thought about studying those terrible places s a scholarly activity, but I am much persuaded of the intellectual value of intense examination of POWs and prison camps by recent scholarship such as the book you reviewed and another book that came to my attention just last night for what they tell us about that experience of Civil War soldiers and the politics that made prison camps such horrific places.

Gary Morgan, a history teacher from Massachusetts, has written what I suspect may long stand as one of the most thorough, if scholarly heretical, studies of Andersonville. Her book, Andersonville Raiders: Yankee Against Yankee in the Civil War’s Most Notorious Prison Camp, focuses on one of the most well known elements at Andersonville. This is the Raiders, men who victimized — including killing — their compatriots and were ultimately (with the approval and support of the Confederate commander and guards hanged in a group in July 1864. Anyone who has ever visited Andersonville knows that the graves of the Raiders are very clearly set aside for all eternity from the other soldiers buried in the Georgia graveyard.

Turns out, almost everything we thought we knew about Andersonville’s Raiders isn’t true, including the names and activities of the men who were hanged. One would be inclined to disagree with Ms. Morgan because her findings run so contrary to conventional scholarship, except she has carefully collected the contemporaneous historical documents to support her views. It’s hard to argue with the official records, particularly when they are supported by other records.

People who would enjoy the book reviewed might also want to take a look at Ms. Morgan’s work. It will be well worth your attention.