Supporting the Cause: Union and Confederate Patriotic Envelopes

ECW welcomes guest author Leon Reed

About three years ago, my cousin, Jim Reed asked if I’d like to see a scrapbook that had been kept by a civil war ancestor of his. What I got was an incredible collection of original correspondence, photographs, souvenirs, and, most of all, patriotic envelopes from the secession crisis and the first year of the war. The collection was assembled by Hiram Roosa of Kingston, NY, who served during the war as the corresponding secretary of the New York Military Association.

These envelopes (also called covers) were an important way for people to show their support for the cause. Many made simple patriotic statements; while others celebrated the hero of the moment, a fallen “martyr,” or a recent victory; and others trash-talked the other side.

I realized as I worked through the collection that these are more than illustrations: somewhat like the insight William Frassanito had during his study of Gettysburg photos, I realized that they’re also valuable historical documents. Perhaps most important, they provide insights into public opinion. The printers were printing these covers to sell them and they would have kept careful track of what seemed to be selling. Did that “fallen hero” envelope sell well? Let’s look for another fallen hero. Did that cover showing Jefferson Davis with a noose around his neck do well? Let’s do another one.

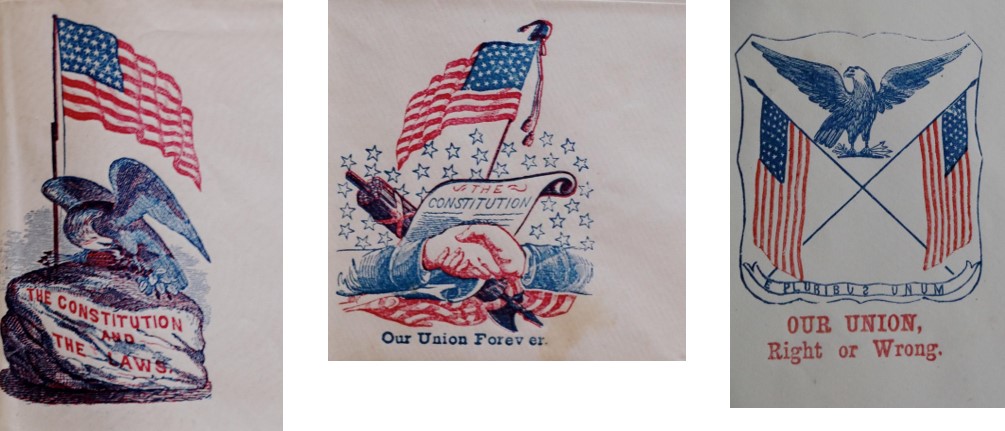

Many of the envelopes simply expressed a “hurrah for our side” patriotic sentiment. But the North and South had quite different views of what constituted a patriotic sentiment. Northern printers cited the Constitution, the laws, and the permanence of the Union.

They called back to nationalist symbols (Liberty Bell, Old Ironsides) and heroes (Washington, Webster, Jackson). They carried an unmistakable message: the Union is permanent and indivisible.

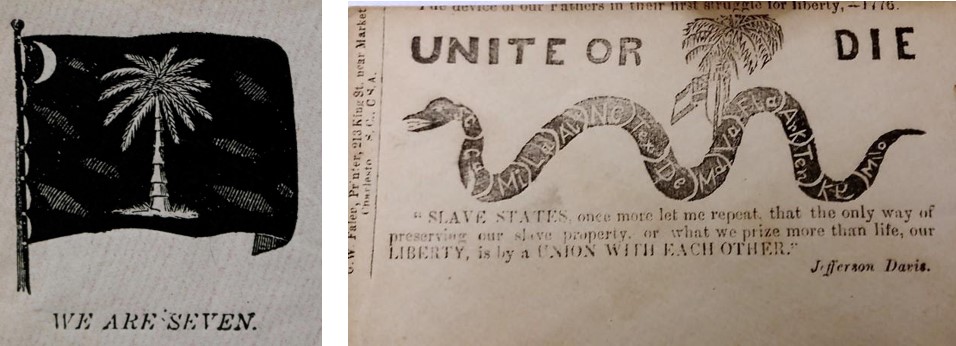

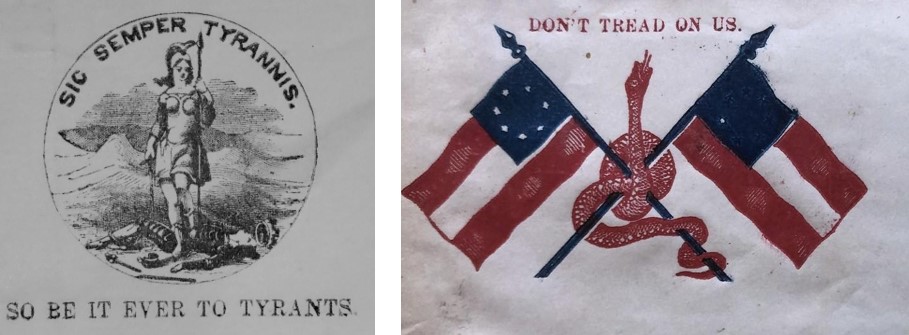

The Confederates took an entirely different approach. The Confederates cited the birth of the United States in rebellion. As their authority, they called back to the Declaration of Independence, with its statements about the right of the people to alter or abolish a tyrannical government. The “Ever Ready” cover is a reference to the final line of the Declaration, in which the signers pledged “our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.”

“We are Seven” simultaneously celebrated the South Carolina palmetto flag and also the formation of the Confederate States of America with its original constituency of seven states. “Unite or Die” was an early cover and referenced Benjamin Franklin’s famous snake cartoon to call on the newly seceded states to gather and form a new nation.

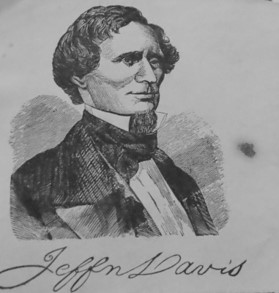

Jefferson Davis was also an important figure. As the war moved on, Davis became more and more associated as a symbol of Confederate nationalism.

Aside from the references to the Declaration of Independence, Confederate patriotic envelopes also tended to be somewhat more pugnacious than the strictly patriotic northern covers. As a new country trying to establish a sense of identity, nationalist symbols were especially important.

The set of envelopes I just discussed gives insights into the different ways the North and South justified their causes. After my study of patriotic covers (envelopes), I’ve come to the conclusion that they are important historical documents. Like diaries and newspaper articles, they provide insights into public opinion and illustrate some of the important events and people of the secession crisis and the onset of the war. The covers had largely faded away by 1863, partly because of shortages of paper and ink, especially in the south, and partly, I’m sure because the mounting casualty list reduced the enthusiasm of many people about displays of support for the war.

Leon S. Reed is a retired career switcher ESOL and US History teacher (Woodbridge High School, Virginia). Before that, he worked for the US Senate Banking Committee and was a defense consultant.

Reed has always had a passion for military history and particularly the Civil War, and particularly Gettysburg. His great-great grandfather, Morgan Snyder, who was in the 55th Ohio, fought at Gettysburg.

He moved to Gettysburg when he retired and had a chance to pursue my interest in the Civil War: exploring the battlefield on my bicycle, volunteering for the National Park Service (in their Resource Room, where we help people research visitors’ Civil War ancestors, and in the education program), writing and photographing for “Civil War News,” and guiding tours at the Jenny Wade house.

Leon Reed

Thanks for sharing your collection of Patriotic Covers with us. There were a lot more designs, continually changing, North and South, than most folks would believe…

A couple of years ago I ran across the attached YouTube video of an amazing find in Delaware: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VdlpXsgSfTs

I enjoyed this post. New insights. Thanks for sharing.

—Chris Barry

Very cool! The Special Archive Collection at Tulane University in New Orleans has a great collection of Union postcards. Some of the political cartoons printed on them were pretty funny. They definitely don’t pull the punches on poking fun at the Confederate government or officers.

Thank you for this interesting article. They are historical documentation/evidence for many reasons addressing many disciplines.