Not Written in Letters of Blood: Tullahoma

On July 7, 1863, William Rosecrans, in reply to a telegram from Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, wrote: “I beg in [sic] behalf of this army that the War Department may not overlook so great an event because it is not written in letters of blood.”

Rosecrans was referring to the recent operations of the Army of the Cumberland in late June and early July 1863; more commonly known as the Tullahoma Campaign.

The Tullahoma Campaign is, by and large, still undiscovered country for most students of the Civil War. Many people know of Tullahoma, I have found, but not many know much about Tullahoma.

There are at least three overriding reasons for this obscurity. First, neither the Union nor Confederate commanders were top talent. Immediate draws of the likes of Grant, Lee, Sherman, or Stonewall Jackson; none were present in Middle Tennessee. Second, the campaign lasted slightly more than one week and ended without a climactic battle. Today no national or even state park exists to preserve its story. Third, Tullahoma is overshadowed by two other great events that happened simultaneously: Gettysburg and Vicksburg, both of which overpowered news of Tullahoma even as it was happening.

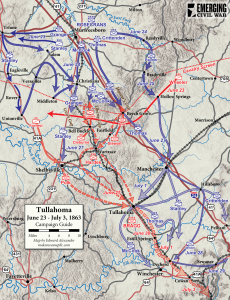

Despite that obscurity, Tullahoma has another reputation, passed as if by word-of-mouth; as one of the truly remarkable examples of military movement in the Civil War. For over the course of roughly eleven days, from June 23 to July 4, 1863, Union Major General William S. Rosecrans unleashed a campaign of deception and maneuver that so baffled his Confederate opponent Braxton Bragg that the Rebels were driven completely out of Middle Tennessee, surrendering a huge swath of the state to Federal control as the retired to Chattanooga, in the very southeast corner of the state.

Faced with extensive Confederate earthworks and the daunting real estate of the highland rim, Rosecrans repeatedly eschewed frontal assaults and leveraged Bragg out from behind works at Shelbyville, Wartrace, and the Confederate supply base at Tullahoma. Rosecrans orchestrated a successful campaign, remarkably devoid of endless casualty lists flooding hometown newspapers, won at a cost of less than 600 Federal soldiers. Bragg’s losses were heavier, but mostly in deserters and captures; none of the actions fought over the course of those ten days were particularly bloody.

In the end, Bragg’s army escaped to fight another day, avoiding disaster by the thinnest of margins, thanks in part to the abnormally heavy rains that fell during that ten-day stretch. Bragg’s escape provides yet another reason why Tullahoma has been overlooked. It feels like a prelude, not a decisive stroke in its own right. Two months later Rosecrans and Bragg faced off again, this time for control of Chattanooga, and that confrontation did result in an epic collision: Chickamauga, the second-bloodiest battle of the entire war.

But Tullahoma is not without its moments. There were sharp fights at Hoover’s and Liberty Gaps, a sizeable cavalry engagement at Shelbyville, and a number of smaller actions usually waged for control of various river crossings. One such scrap occurred on July 2, 1863, on the banks of the Elk River—which produced at least seven awards of the Congressional Medal of Honor, all to men of the 104th Illinois Infantry. This is an impressive number, given the size of the fight: On the same day at Gettysburg, amid the largest battle of the war, only 22 such medals were awarded.

On the morning of July 2, the 104th Infantry led Major General James S. Negley’s division of the 14th Army Corps to the site of Bethpage Bridge over the Elk, pursuing Bragg’s retreating Rebels. With the Elk in flood stage thanks to the recent rain, any fords were largely unusable, rendering the handful of existing bridges over the river as highly desirable military targets. When Federal brigade commander John Beatty realized that the Bethpage Bridge was still standing, guarded by an occupied Rebel stockade on the north bank, he decided to try and seize both structures. However, the stockade was solidly built, with good fields of fire; moreover, Confederate dismounted cavalry and artillery supported the stockade from the south bank, prepared, said Beatty, to “open on us whenever the head of our column should make its appearance in the turn of the road.”

Any Federals moving against the stockade would be subject to a galling fire, leaving Beatty to conclude that “it would be useless to expose my infantry” without support. Instead, he called up two batteries, and once emplaced, ten Union cannon opened up against both the Confederate guns and the stockade. Within “forty minutes,” the Rebel artillery was overwhelmed and fell back, allowing Beatty to push a skirmish line forward. There was still the matter of the stockade, however.

During the action, the Rebels managed to set the Bethpage Bridge alight, which added urgency to Beatty’s mission. Losing the bridge would greatly delay any Union pursuit across the Elk for a day, maybe more; buying yet more time for Bragg to escape over the Cumberland Plateau. In response, Beatty ordered Col. Absalom B. Moore to try and capture the bridge. That couldn’t happen, however, until someone dealt with the Confederate sharpshooters garrisoning the stockade.

Moore turned to Sergeant George Marsh of Company D, asking Marsh “to lead a squad to reconnoiter, and if possible, take the stockade.” Marsh, in turn, called for volunteers: “all who are not afraid, fall in!” He “took the first 10 who stepped forward.”

Deploying his small band, once they were ready, Marsh led the way down towards the enemy “at a double-quick.” They did so, the Sergeant recalled, “under a heavy fire of musketry and artillery” from both the south bank of the river “and at first from the stockade.” Amazingly, all eleven Yankees survived the dash to reach the stockade wall, unwounded.

Here, the next surprise occurred. Marsh and his compatriots had so far not fired a shot. They now, according to Marsh, “forced and entrance into the stockade . . . [and] emptied our rifles into the Confederates” inside. This fusillade did the trick. “Upon seeing us enter the fort,” said Marsh, the Rebels “climbed the stockade[‘s]” opposite wall “and ran up the bank.”

The 104th’s regimental history noted that the dozen rebels left to hold the stockade, “seized with a panic at the bold action, left in confusion, swimming the Elk, took to the woods, from which they sent back a few shots. The [assault] party was soon after ordered back and received the personal thanks of the General. [Beatty.] Captain [George W.] Howe, with Company B, was then sent down with a detail to put out the fire at the bridge.” Howe and his men extinguished the flames and saved the bridge in sound enough condition to be used to cross the infantry.

Marsh’s dramatic charge was observed with enthusiasm by Beatty, Col. Moore, and numerous other federal observers. They never forgot it, and, in 1897, Sergeant Marsh and his companions were each awarded the Medal of Honor. Of those ten men who made the charge, only seven could be named in 1897, and are recorded for posterity. In addition to Marsh, they were John Shapland, Oscar Slagle, Reuben Smalley, Charles Stacey, Richard J. Gage, and Samuel F. Holland. Marsh’s citation reads: “for having led a small party at Elk River July 2, 1863, captured a stockade and saved the bridge.”

Earlier this year, I traveled to Ottawa, Illinois, looking for the grave of a particular soldier: Major General W. H. L. Wallace, who was mortally wounded at Shiloh. However, I also knew that the 104th was from that area, with several veterans of the 104th buried there.

David Powell and Eric Wittenberg have co-authored a new volume on Tullahoma, recently published by Savas Beatie: Tullahoma: The Forgotten Campaign that Changed the Course of the Civil War, June 23-July, 1863

A nice post. The new book is excellent and very strongly recommended.

Indeed a good book.

I believe what you should have said is that the Tullahoma Campaign generals were not the usual Virginia-centric cast of characters that dominate popular Civil War histories.

I agree with your statement.

You are exactly right. The Tullahoma campaign is widely overlooked. I’m a Civil War enthusiast, but I barely knew anything about Tullahoma. I’ll be ordering your book.

I am planning on going over to the bethpage bridge and see if i can locate the stockage remnants or some sign of it..i love History and the civil war era especially excites me.My fiance is the same way she loves all history from all different back grounds …any relics i might find wil be turned over to the historical society in winchester tn.. my home town…I would love to find someone for us to metal detect with ..it’s hard to find a good place these days because in the past people left their holes uncovered and left trash everywhere ..with todays modern machines you can narrow down a target within a 3 inch circle while its still in the ground..

Hello, Mr. Powell,

I have a question that doesn’t actually pertain to this topic, but I couldn’t seem to find another way to make contact.

I am researching Colonel Allen Buckner of the 79th Illinois Infantry. I found two bibliography citations you included in a couple of your books to a memoir by Allen Buckner. This is one of them:

Allen Buckner, Memoirs of Allen Buckner (Lansing, Michigan Alcohol and Drug Information Foundation, 1982), 1–8, 18, Wells, “Chickamauga,” 222. 5. OR 30, pt.

I have tried and tried to find a copy of these memoirs and can’t, so I hoped you would take pity on me and tell me if you know where I could access a copy.

Col. Buckner was a Methodist pastor in my hometown at the time the Civil War started, which is why I am researching him.

Any help you might be would be greatly appreciated.

Clementine

Clementine, sorry for the late reply. I managed to get a copy of Buckner’s memoir via Interlibrary loan, and so I can’t remember who lent it to my home library. I know it is _extremely_ hard to find. Here, via Worldcat, is a link showing four libraries that claim to have it. I say claim, because I have run across cites that are no longer accurate in the past.

https://www.worldcat.org/title/memoirs-of-allen-buckner-colonel-of-the-79th-illinois-volunteer-regiment-in-the-civil-war/oclc/22238181&referer=brief_results

Good luck.