Book Review: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

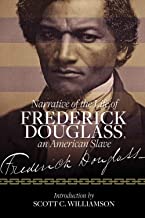

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave

By Frederick Douglass, Introduction by Scott C. Williamson

Mercer University Press, 2021, $16.00 paperback

Reviewed by David T. Dixon

Frederick Douglass hardly needs an introduction to students of the American Civil War. David Blight’s 2018 Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of one of the most famous nineteenth century persons of color stands alone as the definitive treatment of his life. But in 1845, Douglass was not yet a world-renowned orator and civil rights champion. His autobiography was his first appearance to a broad public audience on a national stage and featured a man of superior intelligence, incisive analytical skills, and a remarkable facility for language. Many contemporary white readers only familiar with racist tropes and stereotypes were taken aback by Douglass’s intellect and eloquence and shocked by his candor.

“I often found myself regretting my own existence and wishing myself dead,” recalled Douglass in 1845, less than seven years after he escaped from bondage. “I have no doubt that I should have killed myself, or done something for which I should have been killed.” The depths of anguish and despair in this first of Douglass’s three autobiographies offered readers a stark, intimate glimpse of the insidious evils of chattel slavery. First-hand accounts of formerly enslaved people exposed the hypocrisy of slaveholders’ assertions that this savage institution was divinely ordained. “Between the Christianity of this land, and the Christianity of Christ,” Douglass contended, “I recognize the widest possible difference.”

Douglass’s compelling narrative remains relevant today as Americans grapple with realizing the elusive ideal of equality promised in the Declaration of Independence, envisioned by Lincoln in the Gettysburg Address, and fought for by civil rights activists like Martin Luther King and John L. Lewis. In the 21st century, the battle over Civil War memory continues in earnest amid renewed racial tensions. Reading Douglass’s autobiography alongside state secession ordinances does much to dispel the final, futile whimpers of present-day Confederate apologists and the Lost Cause lies of happy, contented enslaved people.

Douglass himself anticipated and exposed the sham of future Lost Cause mythology when he recalled traditional Christmas holiday celebrations wherein ostensibly benevolent masters granted enslaved workers a weeklong furlough from their labors. This custom, according to Douglass, was a “gross fraud” designed to “disgust their slaves with freedom” by plying them with liquor, thereby “plunging them into the lowest depths of dissipation.” Feeling as if they might as well be “slaves to men as to rum,” this cunning deceit was designed to manipulate enslaved people into contemplating a scant difference between prospective liberty and their present condition. Why run away if freedom consists of depravity and debauchery?

Douglass finally found hope, redemption, and the courage to escape his fate not in faith, but through literacy. His arduous and secretive efforts to teach himself and others to read and write exposed him to the writings of abolitionists and future white allies like William Lloyd Garrison while arming himself with the rhetorical weapons and confidence he would need to survive as a free man in a North dominated by white supremacists. Douglass dared not reveal intimate details of his escape, lest he endanger those who helped him along his path to freedom. Once the book had been published, Douglass himself was forced to flee to England for his own personal safety.

Mercer University Press’s reprint of Douglass’s classic bestseller (it went through nine editions and had sold more than 30,000 copies by 1860) features an unusual forty-eight-page introduction by Scott C. Williamson, Professor of Theological Ethics at Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary. Mercer published Williamson’s biography of Douglass in 2002, focusing on his moral and religious thought.

Williamson begins his lengthy introduction by comparing Douglass’s escape to freedom with Henry David Thoreau’s escape to Walden Pond in a quest to live a simpler life. It is a novel and jarring comparison that may strike a discordant note with some readers accustomed to more traditional approaches to the editing of slave narratives. Is Williamson trying too hard to impose the interdisciplinary approach of Mercer’s “Voices of the American Diaspora Series” by inventing this unusual juxtaposition? Thoreau’s longings for solitude certainly appears as a rich white man’s problem when contrasted with an enslaved person’s dire dilemma and burning desire for freedom; yet Williamson argues that by comparing these two seekers, one may discern similarities in their experiences as each yearned for different kinds of freedom. The contrast between their relative stations in life holds more promise for understanding the immense gap between the black and white experiences in the mid-nineteenth century; a yawning chasm of racial intolerance and injustice that vexes us to this day.

No understanding of the Civil War period is complete without some knowledge of Frederick Douglass. To read him tell of his experiences as an enslaved person and share his hardship, hopes, and setbacks is a moving exercise in fathoming what the publisher calls “the waking nightmare of American slavery.”

David T. Dixon is the author of Radical Warrior: August Willich’s Journey from German Revolutionary to Union General (Univ. of Tennessee Press, 2020).

Accurate review of Douglass’ first hand account of his life in our great American experiment. This is a must read autobiography especially for all of us who are dug in on what we believe. An eye opening account of human nature, human thought and human life in and out of bondage within the US caste system. Appreciate your scholarship sir