Things I learned on the way to Atlanta – not all wounds are obvious.

In 1862, Henry F. Vallette, a resident of Naperville, Illinois and Treasurer of Dupage County, helped organize the 105th Illinois Infantry, a three-year regiment, which mustered into Federal service in September. The regiment was rushed to Kentucky, to oppose Braxton Bragg’s invasion of that state, but saw no combat. Instead, they spent the next eighteen months chasing guerrillas and guarding railroads. In the Spring of 1864 they were assigned to the Third Division of Joe Hooker’s XX Corps, joining an organization of largely Eastern troops from the XI and XII Corps, though Butterfield’s contingent were, by and large, not former Army of Potomac men.

Their first combat was Resaca, on May 15. They were in William Ward’s brigade, which included (and was sometimes commanded by) future president Benjamin Harrison’s 70th Indiana Infantry. Formed in column of regiments, with the 105th last, the brigade assaulted Max Van den Corput’s Cherokee Artillery, which was dangerously exposed in a small earthwork 80 yards in front of the main Confederate line.

Lt. Col. Henry Vallette participated in this attack, which devolved into a bloody, confused struggle for the earthwork. In the end, Ward’s men overran the gun, but at a heavy cost: 422 casualties. The 105th lost 48 men killed and wounded.

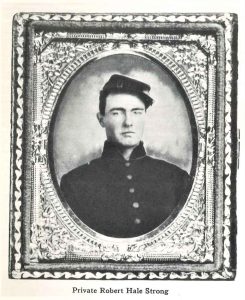

During this action, Vallette fell out. Pvt. Robert H. Strong of the 105th later wrote that Vallette “got so badly scared that he soiled his breeches. He never got over that scare. Anyway, he left us during our next fight and we never saw him again until we got home.” Though Vallette was listed among the wounded, he was outwardly unmarked, a fact which almost certainly contributed to Strong’s condemnatory opinion in his memoir.[1]

Vallette did resign his commission shortly thereafter, but Strong was wrong: He had been wounded. A subsequent biographical sketch noted that “he was severely injured by the concussive force of a cannon ball, which passed so close . . . that he was knocked down and rendered unconscious.” On May 21st, Vallette returned to the regiment, noted Pvt. Lysander Wheeler of Company A: “He was stunned by a blow from a piece of shell last Sunday, [but] he is getting on all right.” Two weeks later, however, on June 8, 1864, Vallette resigned his commission due to disability, and was invalided out of the army.[2]

Not every combat injury was immediately apparent. Col. Mahlon Manson, of the XXIII Corps, suffered a similar concussive injury only the day before, May 14, during that command’s fight in Camp Creek Valley; he also never returned to duty. But resigning in the face of the enemy while lacking any overt “badge of honor” wound created stigma, Just an added complicating returning veterans were forced to deal with.

Vallette returned to a family, a promising legal career, and continued public service, eventually retiring to California. He died in 1909, and is buried in Long Beach.

[1] Robert Hale Strong, A Yankee Private’s Civil War (Chicago: 1961), 17.

[2] “Col. Henry F. Vallette,” Magazine of Western History, Illustrated. vol. XIII (November 1890 to April, 1891), 240; “Dear Parents, Bro. and Sister,” May 22, 1864, Lysander Wheeler Letters, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, Springfield, IL.

Different battle but similar experience: Major Henry Stark found himself the senior officer in the 52nd Illinois Infantry on Sunday morning 6 April 1862 due to the approved absence of LtCol Wilcox and the elevation of Colonel Sweeny to Brigade command. Following the launch of an unexpected attack by Rebel forces under command of General Albert Sidney Johnston, Major Stark led his regiment south “toward the sound of the guns” and became briefly incapacitated: some say a Rebel shell exploded in close proximity to the Major and dazed him; others believed a large branch high in the trees was sliced through by an artillery round and in process of crashing to the ground struck Major Stark on the head. As in the case of Colonel Vallette, there was no obvious wound, only unexplained “behaviours.” In the case of Major Stark, he seemed awake, yet unable to give commands. So he was replaced as commander of the 52nd Illinois by a Captain; and following the Battle of Shiloh the “still inexplicably impaired” Henry Stark was forced to resign. Upon his arrival back home in Sycamore Illinois, it was discovered that letters had already circulated there claiming “Major Stark faked his injury to get out of the War.” With the entire community against him, and unable to “prove” the cause of his still lingering condition, Stark and his wife left Illinois and relocated to a small town (said to be in Pennsylvania) and effectively “withdrew from the world.”