Things I learned on the way to Atlanta—What happened at Cassville?

Cassville – May 19, 1864.

The opening stages of the Atlanta campaign are defined by two “lost opportunities.” The first of those is Snake Creek Gap, the mountain pass supposedly unnoticed by the Confederate Army of Tennessee while entrenched at Dalton, which Federal General William T. Sherman used to surprise and nearly trap Rebel commander Joseph E. Johnston, thereby ending the campaign at a stroke. Only the timidity of the officer commanding that flanking column, Grant and Sherman protégé James B. McPherson, prevented the Federals from capturing Resaca—or, at least, so goes the tale.

As might be expected, the reality is considerably more complicated. But that story has been examined and re-examined, and is now a tale oft told.

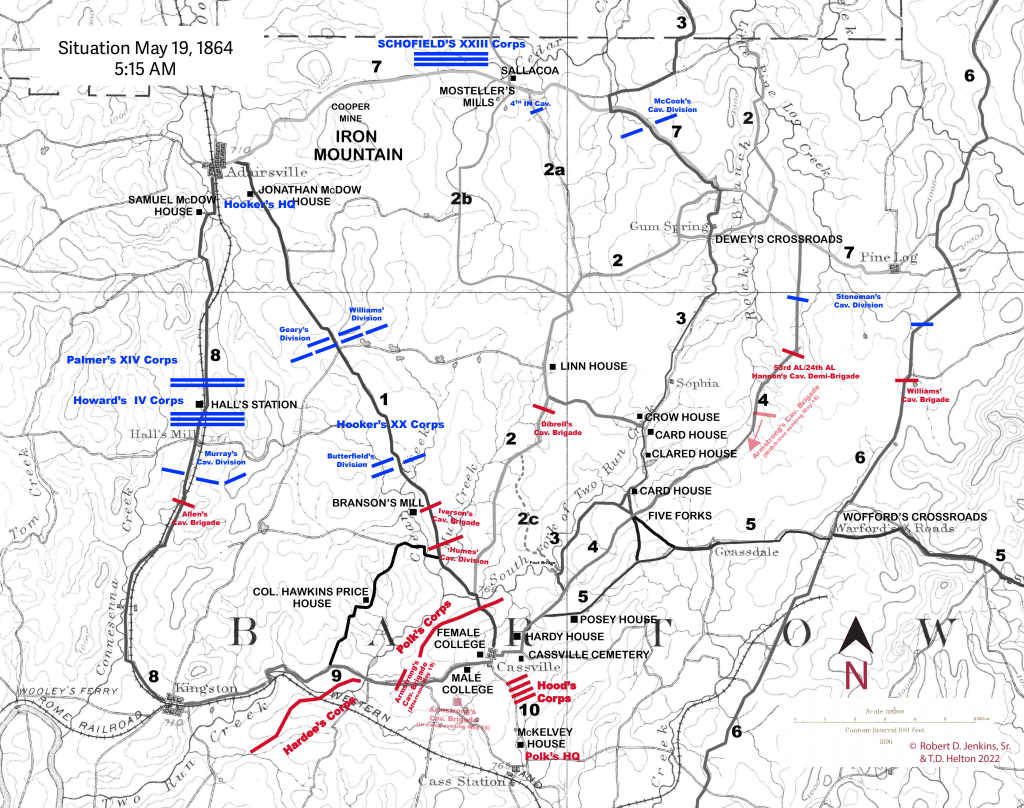

The second “lost opportunity” is Cassville. It is sort of a mirror image of Snake Creek Gap. Here, on the night of May 17, the wily Joe Johnston at last turns his formidable defensive skills, heretofore employed only in retreat, to the business of setting a trap for Sherman. By dividing his forces at Adairsville Georgia, Johnston sent columns to both Kingston and Cassville on the 18th, which are connected by a lateral road—thus forming a triangle. Then, the column at Kingston (William J. Hardee’s Corps) will hurry to join Johnston at Cassville. The marches were well executed, and Johnston’s entire army was assembled at Cassville by the afternoon of the 18th.

If Sherman took the bait and also divided his army in a similar fashion, then, Johnston reasoned, the Army of Tennessee could attack that portion of the Federal army that marched to Cassville.

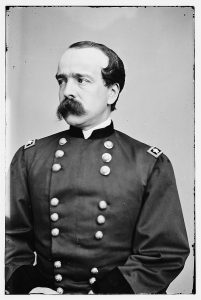

The plan was good, and it almost worked. Sherman was advancing on a broad front: at least two corps—the XX and XXIII, under Generals Joseph Hooker and John M. Schofield—did indeed seem to be headed for Cassville. All was ready for a grand offensive. On the morning of the 19th, Johnston even issued a belligerent General Order, informing his army that the fight they had all been expecting was at hand, and that the Army of Tennessee was done retreating.

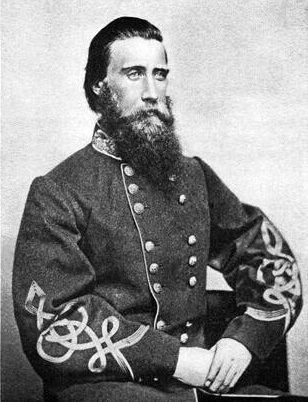

Accordingly, Johnston ordered John B. Hood to take his corps back north along a “country road” parallel to the Adairsville-Cassville Road to attack this column’s left flank while Leonidas’s Polk’s corps-sized Army of Mississippi, deployed astride the road, attacked its nose. Unfortunately for Johnston, Rebel cavalry commander Joseph Wheeler left a road unguarded, allowing a Union cavalry division to slip in behind Hood’s column while Hood was deploying, completely surprising Hood and forcing him to call off the attack. The Rebels fell back, first to one defensive position, then another, all while Sherman’s forces continued to arrive. That night, Johnston retreated across the Etowah River. The first stage of the Atlanta Campaign—the First Epoch, as Union mapmakers labelled it—was over.

Much ink has been spilled about this failure, almost all of it from the Rebel perspective. Johnston never believed that Hood was actually attacked by any Federals; in turn, Hood later accused Johnston of lying about what happened. The controversy carried on for decades, as both men waged literary warfare over the “missed opportunity” at Cassville. Historians have sifted the evidence ever since, to differing conclusions.

There’s only one problem with this version of events: Sherman never took the bait.

Excepting one Union cavalry division, Sherman sent no Federal troops to Cassville on May 18. Instead, he ordered his whole army to concentrate at Kingston—where he expected Johnston, instead of retreating laterally to Cassville, to simply slip across the Etowah at Kingston and then move back to the railroad at Allatoona in relative safety.

On the night of May 18, only Daniel Butterfield’s division of the XX Corps was even close to Cassville, roughly three miles short of that town on the Adairsville-Cassville Road. And on May 19, neither the rest of the XX Corps nor the XXIII Corps marched to Cassville until mid-afternoon, arriving many hours after Hood’s column had marched out and marched back. They were waiting for the rest of Sherman’s army to come up from Kingston, having discovered Johnston’s real movements, before committing to a fight.

On the morning of the 19th, only a brigade and a half of Butterfield’s division—perhaps 3,000 men—lay within the jaws of Johnston’s trap, while Hood and Polk together numbered about 36,000. Had Hood attacked as ordered, he would be punching mainly into air.

Cassville was never a “lost opportunity” for Johnston, because the Federals weren’t there.

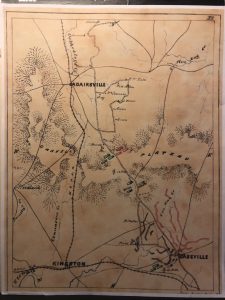

Sherman stated that he would not have attempted the Atlanta Campaign without the highly detailed map that was produced & distributed to top commanders exclusively. Sherman’s copy is in the LOC. Sherman’s conviction that the map was essential is evidenced by a curious incident.

The notoriously impatient Sherman was informed that the map would be delayed for five days. The time was needed to allow “Sgt Finegan & his motley crew…” to finish their work. What could be so vital that a sergeant & motley crew could hold up the invasion of the Deep South for almost a week?

Snake Gap that David Powell referred to above is the answer to that question. Sgt Finegan’s name is in the legend of Sherman’s Georgia maps. He was an artist / architect from Ohio. A cavalryman assigned to the Army of the Cumberland’s remarkable topographic unit, Finegan displayed a genius level ability to gather accurate information from local sources.

In the out of the box thinking typical of the A of the C, Finegan & his motley crew gathered local information from just about anybody who would talk to them. Itinerant peddlers, drovers, poultry herders, talkative geezers, loyal women coming through the lines, you name it, everything was gris for Finegan’s mill.

The top secret limited edition map was printed on heavy paper. It was cut into rectangular sections that would fit into the map pocket of officer’s coats & mounted on linen. The many features that distinguish Sherman’s map from Joe Johnston’s can be attributed to Finegan & his motley crew.

Finegan is easy to look up, apparently he was the only single ‘N’ man of that name in the Union Army. Post war he had a distinguished career as an architect. There is a collection of his papers in Ohio that is on my bucket list.

Fascinating discussion. I’m looking forward to your published study.

The conclusion that I have come to that is highlighted by Powell’s insightful post is that it was the highly detailed & accurate maps that Sherman & his commanders carried that allowed them to avoid traps such as Cassville. The operational advantages the ability to send orders & receive reports oriented by precise maps coordinates can’t be exaggerated.

Very interesting stuff….thank you!