Exploring the Ironclads Monitor and Virginia/Merrimack

On the anniversary of the dramatic clash of the ironclads in Hampton Roads, March 9, 1862, we link to a couple previous articles and share some new stories of the USS Monitor and CSS Virginia (ex USS Merrimack) along with wonderful diagrams by illustrator J.M. Caiella from the recent ECW Series book Unlike Anything That Ever Floated: The Monitor and Virginia and the Battle Hampton Roads, March 8-9, 1862.

See “First Battle of Ironclads: Myths, Facts, What Ifs” and “Around We Go: In the Monitor Turret” for fascinating information highlighted by these illustrations and additional notes.

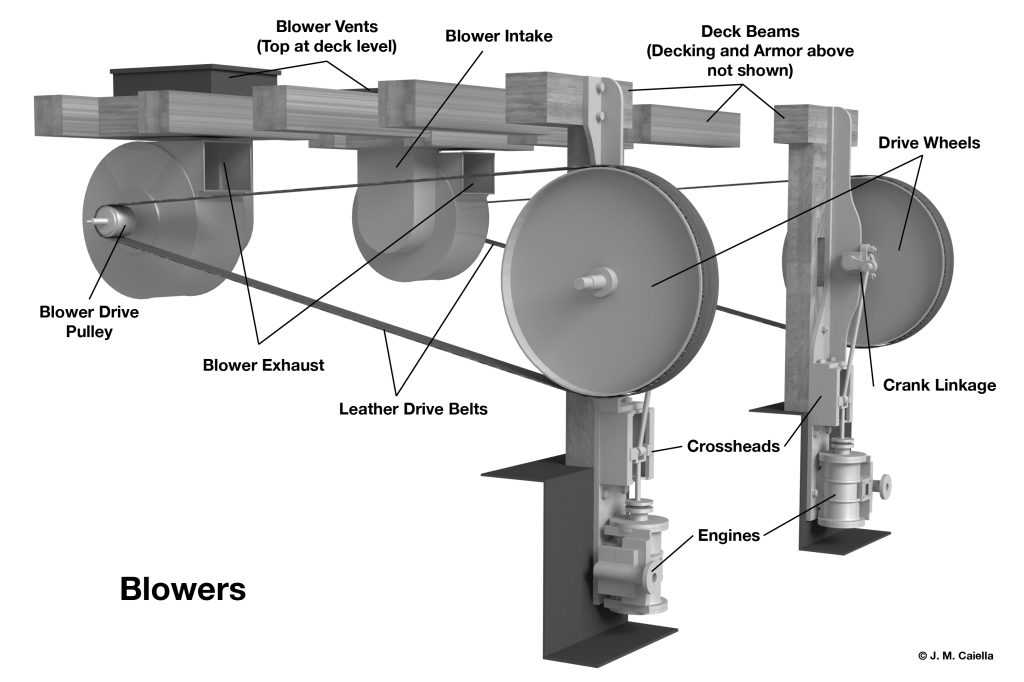

This diagram shows Monitor’s ventilation blowers located behind the engines and below the short ventilation stack on the aft deck. Powered by small auxiliary steam engines and leather drive belts, the blowers were the only source of fresh air for the boilers and the buttoned-up interior.

This diagram shows Monitor’s ventilation blowers located behind the engines and below the short ventilation stack on the aft deck. Powered by small auxiliary steam engines and leather drive belts, the blowers were the only source of fresh air for the boilers and the buttoned-up interior.

The ironclad almost sank on the trip from New York to Hampton Roads a few days before the battle when a severe gale with huge waves dumped tons of water down the short vent and smoke stacks.

Wet drive belts began slipping and blowers stopped. Boilers were deluged in sea water and deprived of air. Steam pressure plummeted; the interior filled with smoke; engines slowed and stopped; pumps were useless, and water began filling the iron enclosure.

Fortunately, the tow ship pulled them into calmer waters where machinery could be restarted. This was in engineering terms a potentially catastrophic “single point of failure.” Taller stacks would be installed later.

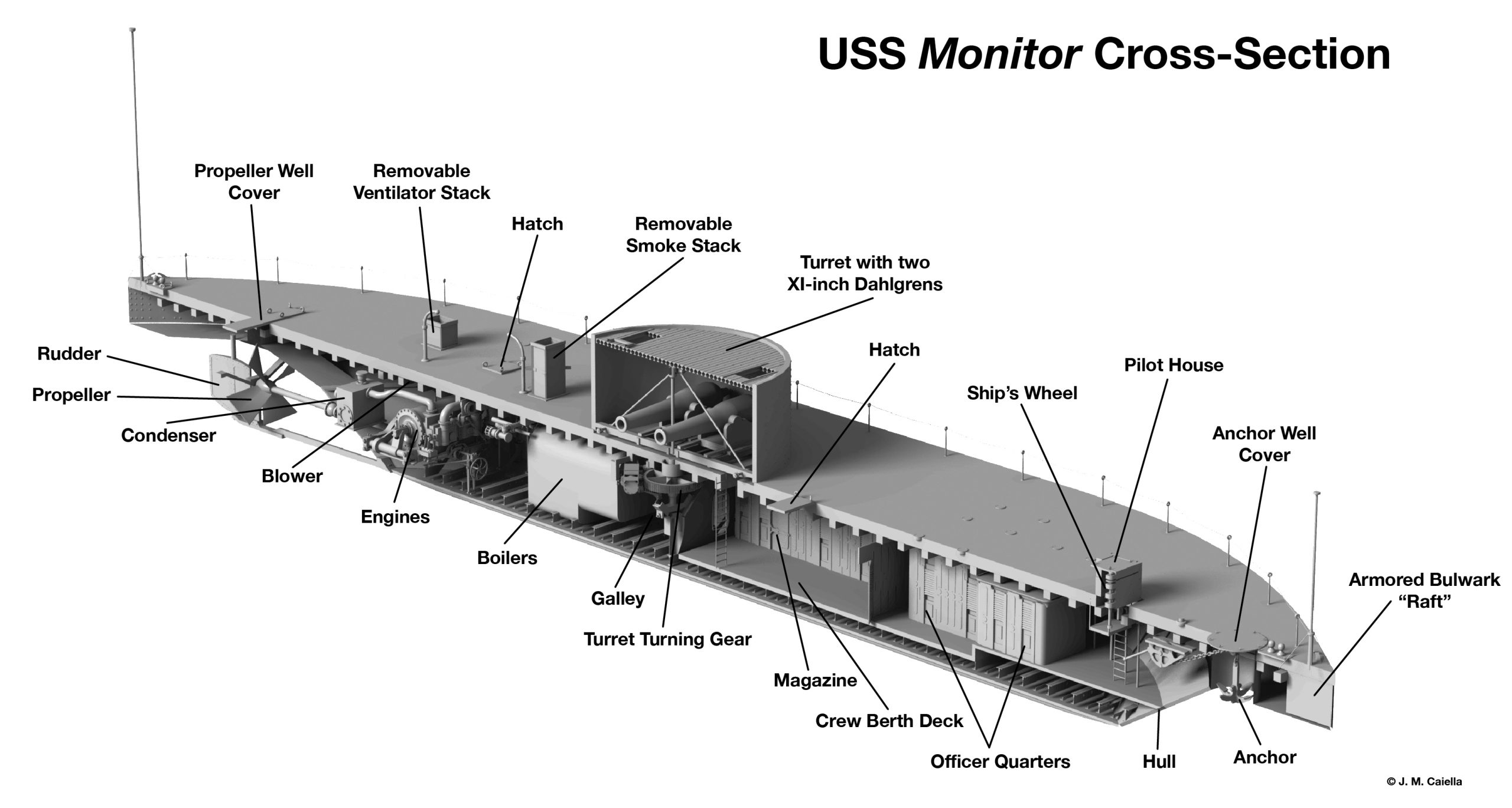

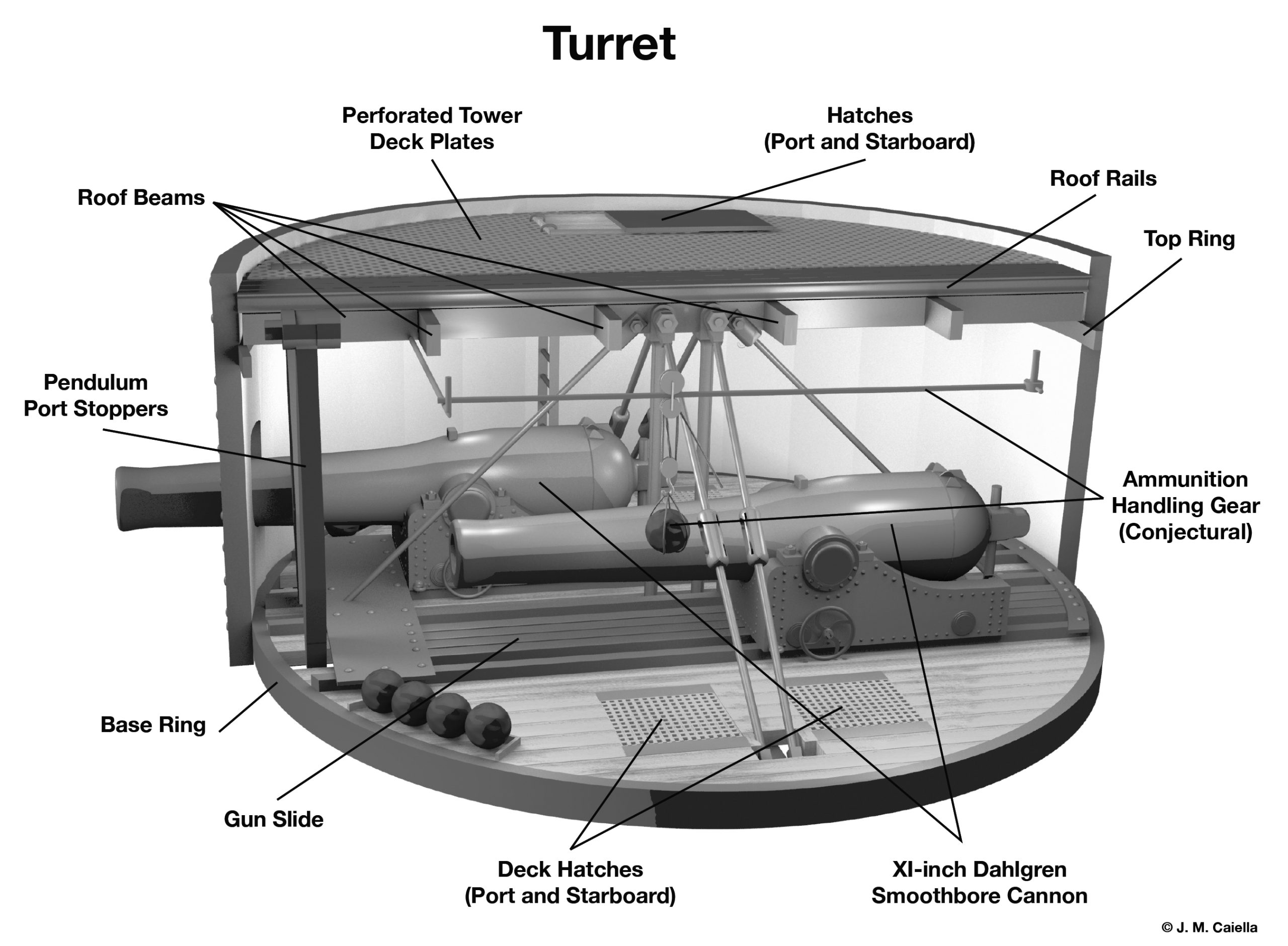

In inventor John Ericsson’s design, the 160 tons of turret was suspended by diagonal braces from and rotated on its central spindle, driven by auxiliary steam engines on large gear wheels underneath.

The spindle would be jacked up for combat, floating the turret a few inches clear of the deck. Otherwise, the turret would be lowered to rest the circumference on a brass ring in the deck, where it could not rotate and proved to be not very watertight.

A British naval engineer developed a superior design with the turret rotating on large iron or steel ball bearings around the base. This concept would supersede Ericsson’s creation in subsequent warships.

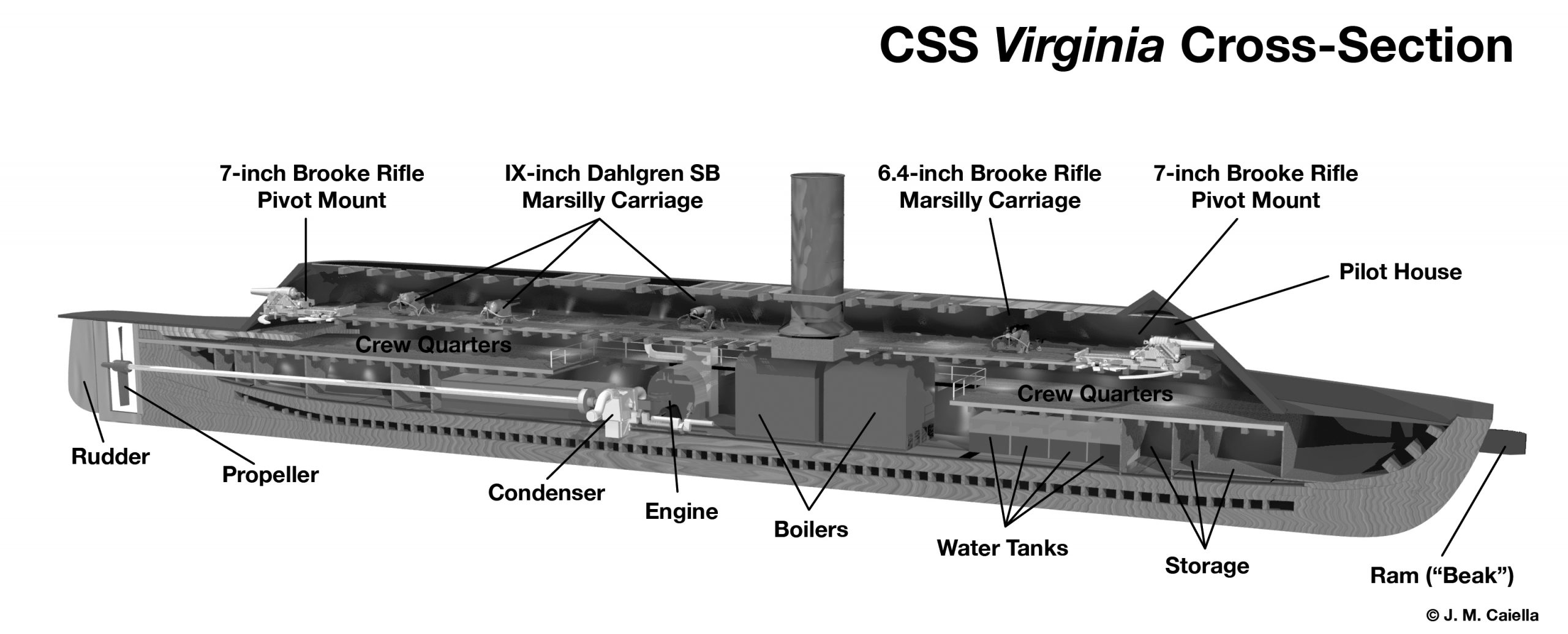

The CSS Virginia was constructed on the deep-draft hull and engines of the former steam frigate USS Merrimack, which severely limited her maneuverability in shallow waters like Hampton Roads. Monitor could run rings around her.

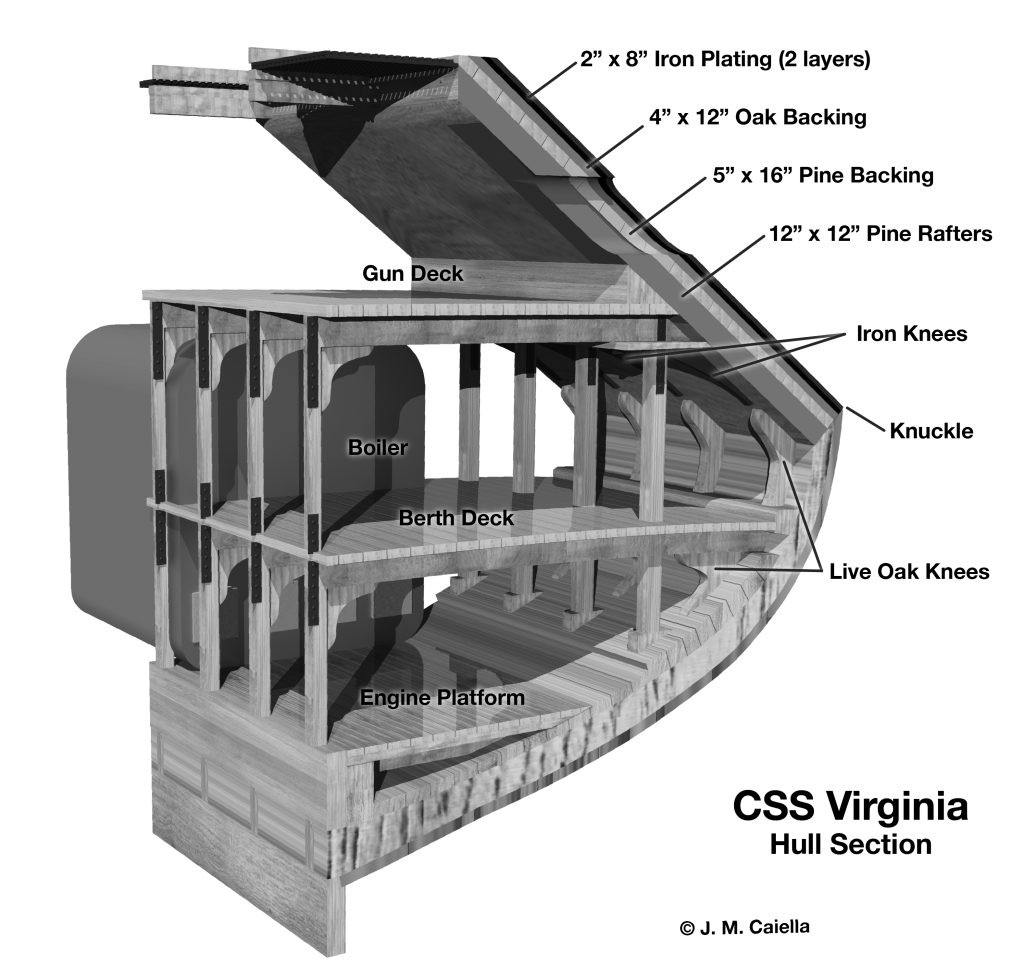

After recovering Merrimack from the bottom of the Elizabeth River, Confederates cut her down to the waterline, built a new gundeck, and covered it with an iron casemate. The “knuckle” where casemate joined hull was considered a particularly vulnerable area.

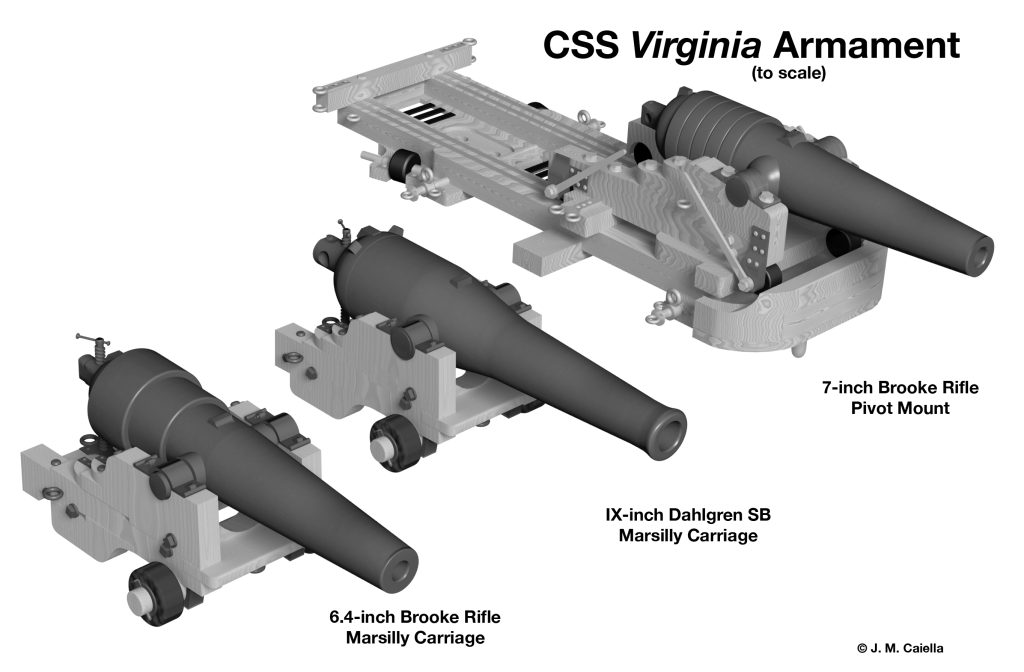

Virginia was heavily armed with six IX-inch Dahlgren smoothbores from Merrimack along with two new 6.4-inch and two 7-inch Brook rifles.

The ongoing revolution in naval armaments produced a confusing mix of ever larger guns with heavier powder charges firing both solid shot and explosive shells through smooth and rifled bores. Containing the increased chamber pressures was a serious problem leading to many a burst gun.

The U.S. Navy’s leading ordnance expert, Lieutenant (later Rear Admiral) John A. Dahlgren designed a gun with increased thickness at the breech called the “soda bottle” for its distinctive shape. The IX-inch Dahlgren became the standard naval weapon; Monitor was armed with XI-inchers, and some XV-inch models were carried on later-class monitors.

The U.S. Navy’s leading ordnance expert, Lieutenant (later Rear Admiral) John A. Dahlgren designed a gun with increased thickness at the breech called the “soda bottle” for its distinctive shape. The IX-inch Dahlgren became the standard naval weapon; Monitor was armed with XI-inchers, and some XV-inch models were carried on later-class monitors.

The Confederacy’s answer to Dahlgren was John M. Brooke, one of the most talented U.S. Naval officers to go South. In addition to leading the conversion of Merrimack to the ironclad Virginia, he designed the highly successful Brooke Rifle with wrought iron bands heat shrinked on a cast iron bore to contain chamber pressure.

One of the what-ifs not discussed in the linked article above concerns the ammunition for Virginia. Brooke also designed armor-piercing projectiles called “bolts.” They were solid iron or steel cylinders with a blunt nose to reduce ricochet and deliver maximum smashing power to an enemy ironclad.

Due to severely limited resources, Brook prioritized production of explosive shells for use against wooden warships, and therefore had no bolts on hand that morning of March 9. He always maintained the bolts would have penetrated Monitor‘s armor.

Lots more stories in Unlike Anything That Ever Floated.

Amazing technology on display! Thanks for sharing on this important anniversary!

Those are some pretty nice illustrations, though it would be interesting to see how the gun system was designed to manage recoil / counter-recoil. I guess at the 9 Mar battle firing was at more or less point blank or less range, so dealing with gun elevation wasn’t an issue. Concerning the use of shell, Hess’s recent book on Army artillery makes much of the problem of developing effective fuses. I wonder how much of an issue that was for naval ordnance in anti-ship role?

Thanks for the comments, Scott. Recoil in the enclosed turret for those big Dahlgrens was a real worry. Never been done before. Ericsson developed customized low-profile friction carriages. The wheel you see on the side of the carriage tightens or loosens clamps on the friction slides to control recoil. In their only test off Sandy Hook, the chief engineer turned the wheel the wrong way and released the clamps. The gun recoiled off the back of the turret leaving a dent that can still be seen. Then he turned the wheel of the other gun the other way and did the same thing before they figured it out. Concern about recoil was also why Worden was ordered to use half charges. He always thought full charges would have penetrated Virginia’s armor, and the Rebs actually thought so too. They also thought solid shot was more effective against armor than shells because they had more smashing power. Shells tended to detonate on the surface without penetrating as they did with wood. Virginia was loaded mostly with shells to go against wood, so didn’t have many solid shot. Confederates thought solid shot would have penetrated Monitor. Lots if fascinating what-ifs.

Thank you, Dwight! Always great to see your detailed posts – especially on a battle anniversary.

Dwight, Enjoyed your talk at Chicago last night.

These illustrations are remarkable! Thank you Mr. Caiella! Were any similar illustrations done for the Passaic Class vessels? Particularly the Central Spindle and pilothouse?