The Moments Before A Sudden Enemy River Assault

The rebels were approaching! The call woke everyone up on the ram Mingo that early morning in June 1862. “Men dazed with sudden awakening, yet with a soldiers’ instinct, darted hither and thither to prepare for the fight.”[1] Near midnight, Colonel Charles Ellet Jr., commanding Mingo and its fellow rams, noticed “ceaseless lapping of water” along the Mississippi River’s bank.[2] It could only be the Confederate River Defense Fleet, launching a surprise attack in the night. For Mingo and the other steamers of Ellet’s United States Ram Fleet, their first combat was at hand.

It was months in the making. Since February 1862, ironclads, mortar boats, and converted wooden steamers of the United States Western Gunboat Flotilla had been pushing down the Mississippi River valley. They helped Ulysses Grant capture Forts Henry and Donelson in February, helped capture Island Number Ten with General John Pope in March and April, and were now bombarding Fort Pillow, Tennessee, guarding approaches to the port and railroad lines at Memphis, Tennessee.

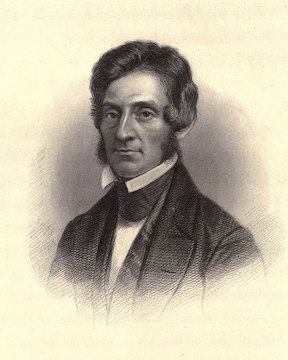

Ellet, a “distinguished engineer,” pressed the need for “steam rams” in February 1862 and after CSS Virginia rammed and sank USS Cumberland in the battle of Hampton Roads, he received permission from Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to buy and outfit a flotilla of steamers designed to ram enemy warships.[3] By May, Ellet had purchased nine steamers, “strengthened their hulls and bows with heavy timbers, raised bulkheads of timber around the boilers, and started them down the river,” all manned by volunteers from army regiments.[4] Ellet was made a colonel and many of his family members commanded their own ships alongside him.

The U.S. Ram Fleet reached Fort Pillow in late May and Ellet wanted to prove the worth of his rams by steaming past the Confederate positions and sinking the Confederate River Defense Fleet. The colonel especially considered the danger of anchoring “within an hour’s march of a strong encampment of the enemy.”[5] Flag Officer Charles Davis, commanding the Western Gunboat Flotilla of ironclads, timberclads, and mortar boats, thought it unwise, but since Davis acknowledged, the rams were “not under my control” and their actions “do not necessarily require my concurrence or approval,” planning continued.[6] They were days from launching Ellet’s plan when the call of the surprise attack materialized.

It was certainly plausible the Confederate River Defense Fleet would launch a nighttime surprise attack near Fort Pillow in early June 1862. Just three weeks before, on May 10, that collection of eight rebel rams “rushed like the wind” and “came on handsomely” in a morning attack that sunk the city-class ironclads Mound City and Cincinnati.[7] The Confederate rams were proven, having “furnished a convincing demonstration of what the ram could do in a fight,” whereas Ellet’s rams remained untested. In fact, just after that Confederate strike naval leadership wrote to the War Department expressing “great anxiety for the immediate descent” of Ellet’s rams.[8]

After hastily waking that June morning, the rams’ crews mustered for battle. Lieutenant George Currie, commanding the ram Mingo, remembered: “Carbines were collected, hand grenades conveniently placed to be thrown on the enemy when within hitting distance; the hoses for throwing scalding water on those who attempted to board, were attached to the boilers, the sharp shooters were placed in [the] most effective positions and commanders moved among all, encouraging each man to stand his post.”[9] Engineers raised steam in the boilers and turned over each ram’s engines as the ships got underway to give battle.

“This is the most depressing experience of a warrior’s life, waiting to be engaged and under a heavy fire from the enemy,” Seaman Bartholomew Diggins recalled in a similar experience on USS Hartford a few months earlier. “One has nothing to do to occupy the mind [and] the mind runs on the great uncertainty about to take place until it is a relief when the battle opens.”[10]

As the rams waited for the River Defense Fleet to appear, they suddenly suspected Fort Pillow’s garrison was along the riverbank, marching forward in a coordinated assault. “On and on stole the enemy, evidence of their steady approach being the snapping of a dead twig or bough, the crunching of a pebble beneath their tread. The shadows of the dense woods lining the shores seemed to be teeming with rebel hordes.”[11] The rail junction of Corinth Mississippi had been evacuated by General P.G.T. Beauregard on May 30. This must be a massive river counterattack to offset that loss.

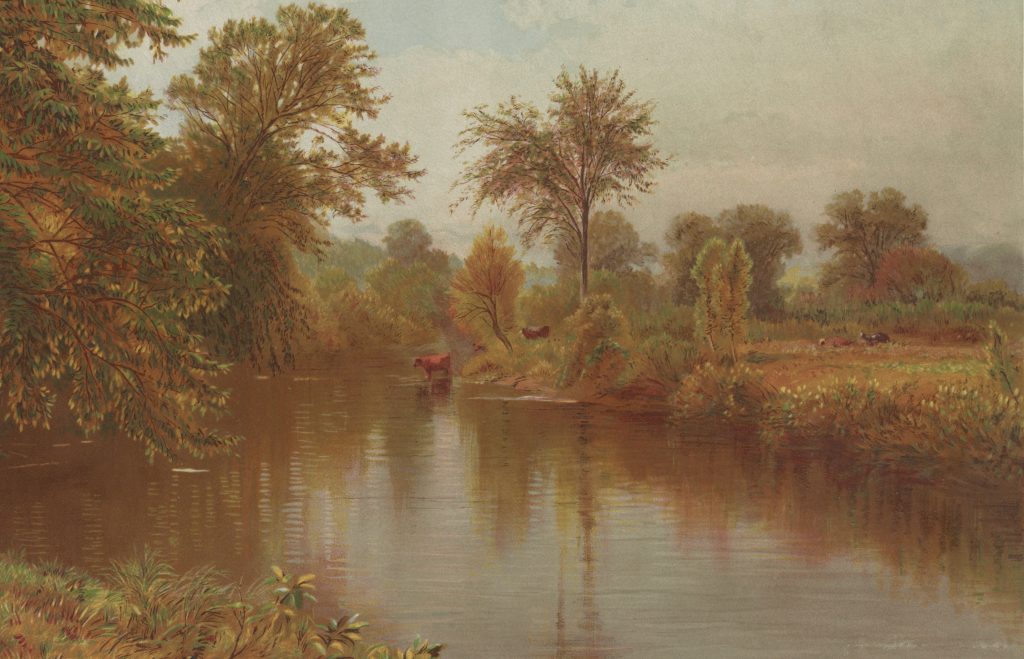

The night was dark, and nothing could be seen in the woods or downriver, but soldiers on Ellet’s rams grew anxious. “Nearer and nearer they draw. Will they never come out from those deep shadows.”[12] Then suddenly things changed. The moment was at hand at last and Colonel Ellet’s soldiers and rams would prove themselves in the maw of combat against Confederate ships and troops. Lieutenant Currie clearly remembered the scene, writing in a letter that “just as it became unbearable the enemy, dauntless, unfearing, appeared right in our post in full view – a great mild-faced moon-eyed cow.”[13]

The great Confederate night riposte never occurred, and Ellet’s men were roused to face off against an errant bovine. For the crews of the U.S. rams, it was a lesson in the tense moments experienced before ‘seeing the elephant’ for the first time. Though not the craziest or most significant anecdote of the U.S. Civil War, for the soldiers manning Ellet’s rams that night, those few minutes before the appearance of that cow might have felt like an entire lifetime unto itself. It is also a testament to the countless incidents during the war where service members believed they were about to enter combat for things to calm down immediately without issue. This particular example evolved into what sailors call ‘sea stories’ that live on via retelling by veterans. Lieutenant Currie was assured his men would never forget “the story of that cow.”[14]

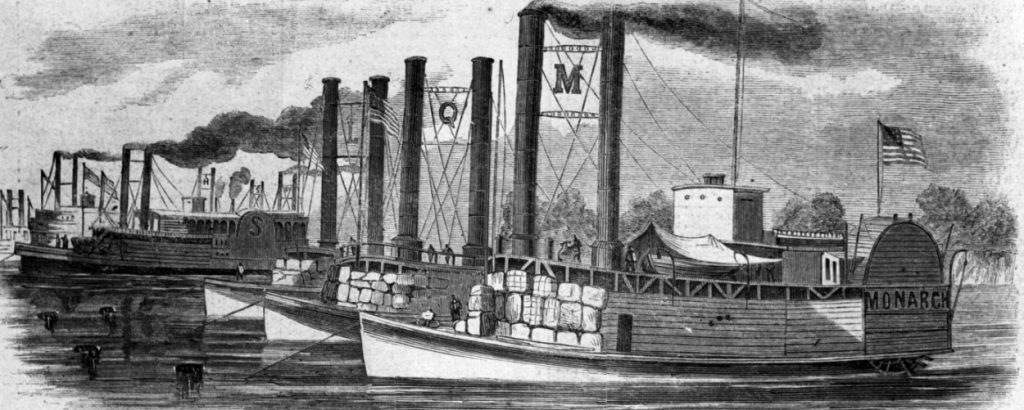

The Confederates at Fort Pillow did not know or care. With Corinth in United States hands, they were outflanked and preparing to evacuate Fort Pillow and Memphis. Ellet’s United States Ram Fleet would face its first action just a few days later. On June 6 the rams Queen of the West and Monarch helped destroy the Confederate River Defense Fleet as Memphis residents witnessed “the engagement from the river banks,” though Ellet himself was mortally wounded in that fight.[15] The surprise cow quicky faded into obscurity as the river war continued.

Endnotes:

[1] Currie to Sir, June 1, 1862, Norman E. Clarke Sr., ed., Warfare Along the Mississippi: The letters of Lieutenant Colonel George F. Currie, (Mount Pleasant, MO: Central Michigan University, 1961, 41-42.

[2] Ibid., 41.

[3] Stanton to Halleck, March 25, 1862, Warren Daniel Crandall and Isaac Denison Newell, History of the Ram Fleet and the Mississippi Marine Brigade in the War for the Union on the Mississippi and its Tributaries, (St. Louis, MO: Buschart Brothers, 1907), 16; John S.C. Abbott, “Heroic Deeds of Heroic Men: Charles Ellet and His Naval Steam Rams,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol. 32, No. 189, (February 1866), 298.

[4] Alfred W. Ellet, “Ellet and His Steam Rams at Memphis,” Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, (New York, The Century Co., 1887), vol. 1, 454.

[5] Ellet to Stanton, May 26, 1862, Crandall and Newell, History of the Ram Fleet, 44.

[6] Davis to Ellet, June 3, 1862, Area 5, Mississippi River, Area File of the Naval Records Collection, 1775-1910, M625, RG 45, US National Archives.

[7] Donald J. Stanton, Goodwin F. Berquist, and Paul C. Bowers, eds., The Civil War Reminiscences of General M. Jeff Thompson, (Dayton, OH: Morningside Press, 1988), 156; Davis to Welles, May 11, 1862, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Commanding Officers of Squadrons, 1841-1886, Mississippi Squadron, M89, RG 45, US National Archives. Both ironclads Mound City and Cincinnati were refloated, towed upriver, repaired, and rejoined the U.S. squadron later in 1862.

[8] Watson to Ellet, May 12, 1862, Crandall and Newell, History of the Ram Fleet, 41, 44.

[9] Currie to Sir, June 1, 1862, Clarke, Warfare Along the Mississippi, 42.

[10] George S. Burkhardt, ed., Sailing With Farragut: The Civil War Recollections of Bartholomew Diggins, (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press), 2016), 16.

[11] Currie to Sir, June 1, 1862, Clarke, Warfare Along the Mississippi, 42.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Thompson to Beauregard, June 7, 1862, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Vol. 23, 140.

This is the first time that I have heard of such a thing as a hose shooting out boiling water being used to attack an enemy. How awful, devilish and brutal a way to die! Not that the other ways weren’t, but burns over the skin are unspeakable. Was this method of weaponry ever outlawed? (Like a Geneva Convention kind of thing?) Does anyone know anything about this??

Hey Judith, it is certainly an intimidating way to defend your ship. I know that other ships were outfitted with similar devices, CSS Manassas for instance. I also know that the Confederacy trained sailors to board Monitor-class ironclads and jam their turrets with wooden wedges to then throw the equivalent of Molotov cocktails or medical jars of what was sed for anesthesia to force crews to abandon ship. There are no recorded instances of that happening during the war, however. Regarding being outlawed, I am not quite sure. Ships operating today in pirate-invested waters often charge fire hoses for use against potential boarders, but I am not sure of anyone connecting these to deliberately heated water.

Thank you, Neil. I appreciate your interest and answer.

Judy S.

A precurser to the notorious mule Brigade…