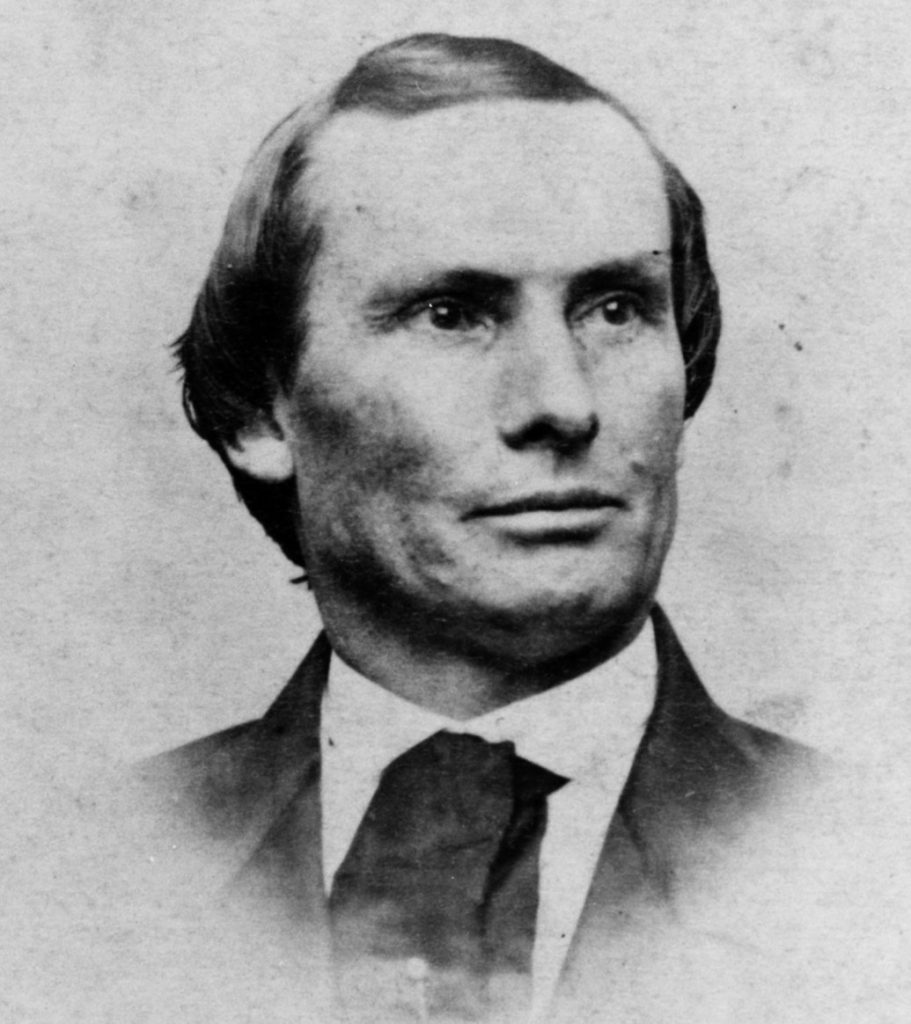

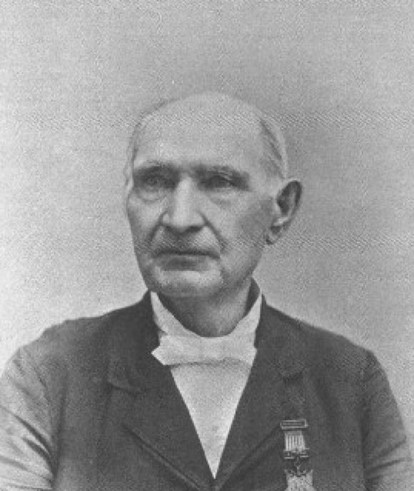

James “Fighting Jim” Jouett of the US Navy

ECW welcomes guest author Sam Dunn

“I ran against a pike held by a man who was braced in the cabin hatchway… I drew the broken pike from my side, struck him over the head with it, and then, threw it overboard.”[i] So wrote Admiral James Edward Jouett in 1879, reminiscing on a desperate Civil War fight that had left him grievously injured eighteen years previously. Jouett’s impressive story, well-known during his lifetime, has since then escaped the attention of a modern audience. Often referred to as “Fighting Jim Jouett”, his forty-nine year career (1841- 1890) took him across the globe and saw him engaging in combat on several continents.[ii] Fighting Jim’s naval career, especially his Civil War achievements, draw attention to the often under examined role of naval personnel at this point in United States history.

Jouett was born in Lexington, Kentucky on February, 27 1828. The son of Matthew Harris Jouett, a famed Kentucky portrait artist and veteran of the War of 1812, James Edward would’ve grown up listening to family stories that highlighted military achievement and glory.[iii] Virginians and Kentuckians may be familiar with his grandfather, Jack Jouett, a regionally famous Revolutionary War hero who rode (in the style of Paul Revere) to warn Thomas Jefferson of an impending British attack in 1781. Jouett’s ride, 40 miles in one night through dangerous terrain, is still remembered and celebrated today. The martial achievements of his grandson, James Edward Jouett, have not garnered the same attention.

Jouett entered the Naval Academy as a midshipman in 1841 and graduated in 1847.[iv] His early career in the Navy was distinguished by his service on the USS Decatur, stationed off the coast of Africa to prevent the illegal trading of enslaved people. Notably, although slavery was still legal in the United States, the importation of slaves was not. He served under Matthew C. Perry, who would later become famous for opening Japan to American trade. Jouett was later transferred to the USS John Adams, where he served during the Mexican-American War.[v]

Jouett’s career, as with so many other naval officers, was altered by the outbreak of the Civil War. Captured by Confederate forces at Pensacola early in the war, Jouett was quickly paroled and assigned to a blockading force outside of Galveston, Texas.[vi] At this point a lieutenant, he distinguished himself in action against the Confederate Royal Yacht on the night of November 7, 1861. According to his own account, while attached to the USS Santee he volunteered to take command of an expedition to destroy two Confederate ships, the General Rusk and the Royal Yacht, which were anchored in Galveston Bay. Jouett’s forty man contingent, twenty men per launch, was armed with a wide array of weaponry, including a twelve-pound howitzer, long-fused shells which would act as grenades, and various other incendiary devices. Jouett led from the first launch.

After failing to surprise the General Rusk, Jouett led his men towards the Royal Yacht. Despite an unfortunate instance of friendly fire when the second attack boat reportedly mistook his men for Confederates, Jouett succeeded in climbing aboard. He quickly made sure that his small launch was securely attached to the larger ship and called down to his men, “now is your time! Come on board!”[vii] Shortly after delivering this command, Jouett was stabbed by a pike-wielding Confederate sailor. The fight itself, recounted at the beginning of this article, was brief but desperate. He later wrote, “it must be remembered that all of this [his wounding and fight against the pikeman] occurred under cover of darkness and much quicker than the story can be told… I found great difficulty in giving an order. The pike seemed to have injured my right lung. Wrapping the folds of my Crimean shirt around my fingers, I stopped up the hole in my side. This made my breathing easier. Thus I sat for three long weary hours”[viii]

According to the Secretary of the Navy, “the Department cannot, in too high terms, express its admiration of the daring and successful exploit of Lieutenant Jouett… The capture of a schooner, well-manned and well-armed, and with every advantage of resistance, after a desperate encounter, speaks well for the intrepidity and bravery of its captors.”[ix]

Jouett’s brave efforts drew the attention of his superiors and he found himself commanding a series of blockade ships, the screw steamer gunboat Montgomery and the screw gunboat R. R. Cuyler. [x] In September 1863, working closely with Admiral David Farragut, he took command of the side?wheel steamer gunboat the Metacomet. While commanding Metacomet, Jouett found himself at the center of one of the most famous naval battles in United States history, the Battle of Mobile Bay.

After the capture of New Orleans in 1862, Mobile Bay became the most important gulf coast port city in the Confederacy. The defense on land was concentrated into three forts, the most formidable of which was the 46-gun Fort Morgan. An array of torpedoes (mines) also littered the water, intended to drive attacking ships towards the guns of the forts. Admiral Farragut, who had long intended to capture Mobile Bay, knew he would have to overcome these formidable defenses if he hope to capture the valuable port.[xi]

At the time of the battle, August 2, 1864, the Confederates had positioned a small but potent naval force inside the bay. Three gunboats, the CSS Selma, Morgan, and Gaines were supplemented by a recently completed ironclad ram, the CSS Tennessee. The Tennessee, far deadlier than her wooden counterparts, boasted four 6.4-inch rifled guns and two 7-inch rifled guns. The hull was protected by iron plate, up to six inches thick in places, making her almost invulnerable to attack. A wrought-iron “beak”, used for ramming enemy ships, was fitted to the bow.[xii]

Admiral Farragut, commanding the West Gulf Blockading Squadron, was well aware of the Confederate defenses arrayed against him. His battle plan was audacious, involving four iron-clad monitors, eight (propellor driven) screw sloops, and six gunboats. The monitors would lead the way, navigating the mine field and dealing with the armored CSS Tennessee. The other fourteen ships, wooden and comparatively vulnerable, would enter the bay lashed together in groups of two.[xiii]

On August 5, 1863 Jouett’s Metacomet was lashed to Farragut’s flagship, the USS Hartford, as the wooden ships formed up behind the ironclad monitor column. The commander of the USS Tecumseh, Captain Tunis Craven, led the monitor formation into the bay. Apparently eager to engage with the CSS Tennessee, he disregarded the torpedo field and led the Tecumseh towards the enemy vessel. This proved to be a deadly mistake. At 7:30, just a few minutes after the start of the engagement, a torpedo exploded through the iron hull of the Tecumseh. According to reports, a great column of water rose into the air and the vessel itself shuddered from the impact. Mortally wounded, the heavy ironclad sunk quickly. Most of the crew, including Captain Craven, were unable to escape.[xiv]

The sinking of the Tecumseh derailed Farragut’s carefully laid plans and left his column of wooden warships dangerously clustered near the edge of the mine field. Farragut, unwilling to lose the initiative, reportedly said, “Damn the torpedoes. Full speed ahead.” Other accounts have amended the quote, reporting that he actually said, ““Damn the torpedoes! Jouett, full speed! Four bells, Captain Drayton!”[xv] An accurate account of the full quote is unlikely to be verified but Farragut’s intent was clear. He intended to lead his force through the minefield, trusting that his flagship, and Jouett’s Metacomet, could clear the way for the rest of the attack force.

Farragut’s bold order, although risky, proved to be the correct one. Many of the Confederate torpedoes had become waterlogged and ineffective. Although the Hartford and the Metacomet collided with several torpedoes as they crossed the field, both ships passed through unscathed.[xvi]

As the formation of US Navy ships entered the bay, they were attacked by the three Confederate gunboats, the Morgan, Gaines, and Selma. The Selma proved to be particularly bothersome, raking the federal ships with devastating fire. Unable to respond from their current position, Farragut ordered Jouett and the Metacomet to cast off from the Hartford and engage the Selma.[xvii]

According to Farragut’s report, “Captain Jouett was after her in a moment, and in an hour’s time, he had her as a prize.”[xviii] A brief glimpse into the action between the Metacomet and the Selma is given by the Medal of Honor citation for Patrick Murphy. Murphy, serving on the Metacomet as a Boatswain’s Mate, was honored for continuing to perform his duties despite damage to the ship and the loss of several men on board.[xix] Regrettably, no further details are provided, but the hourlong gun battle must’ve been harrowing for all involved.

As Farragut wrote, “the coolness and promptness of Lieutenant Commander Jouett, throughout, merit high praise. His whole conduct was worthy of his reputation.”[xx]

With the Selma captured, and the two other Confederate gunboats driven off, the entire Union force turned their attention to the CSS Tennessee. Several of the Union ships rammed the Confederate vessel, raking it with broadside fire as they did so. Union monitors got in close, pounding the Tennessee with large-caliber rifled guns. Although heavily armored, the Confederate iron clad could withstand such a concentrated attack. At 10 o’clock, less than three hours after the sinking of the USS Tecumseh, the white flag of surrender was raised over the Tennessee.[xxi] The naval battle of Mobile Bay was over.

During one of the most hotly contested naval battles of the war, Jouett had again acted with cool resolve. After the Civil War, Jouett continued rise was steady and impressive. He was promoted to the rank of commander in 1866, to captain in 1874, to commodore in 1883, and given command of the North Atlantic Squadron in 1884. Only two years later, he reached the pinnacle of his career when promoted to rear admiral.[xxii]

In his most significant action since the Civil War, Jouett commanded a naval force off of the Colombian-controlled Isthmus of Panama in 1885. Panamanians rising up against the Columbian government, threatened American interests in the area. Jouett, as his obituary states, “succeeded in quelling one of the most serious revolutions in the history of the isthmus.”[xxiii]

Jouett retired from the US Navy in 1890. Congress, recognizing his decades of distinguished services, granted him full pay for the remainder of his life. He lived the rest of his years at his home, dubbed “The Anchorage,” in Sandy Springs, Maryland. Newspaper accounts described him as active and healthy, writing that “every autumn finds him in the saddle riding madly after the hounds as they send a red fox scurrying through the hills of Maryland.”[xxiv] He lived the rest of his life there and passed away on October 1, 1902.[xxv]

Sam Dunn is the Executive Director of the Jack Jouett House Historic Site in Versailles, Kentucky. Before working at the Jouett House, Sam was a staff genealogist with the Sons of the American Revolution and a Lecturer at the University of Louisville. Sam holds a master’s degree in history from the University of Louisville, where he studied industrial education in Kentucky and the historic Eckstein Norton University.

[i] Baber, George: “REAR ADMIRAL JAMES E. JOUETT: A Distinguished Kentuckian and a Heroic Naval Officer.” Register of Kentucky State Historical Society 12, no. 35 (1914): 11 -12. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23368581

[ii] “Rear Admiral Jouett Dead.” The New York Times. 1902-10-02. Retrieved 2023-06-06.: Baber, George: “REAR ADMIRAL JAMES E. JOUETT: A Distinguished Kentuckian and a Heroic Naval Officer.” Register of Kentucky State Historical Society 12, no. 35 (1914): 9. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23368581

[iii] “Rear Admiral Jouett Dead.” The New York Times. 1902-10-02. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

[iv] Ibid.

[v]Havern Sr., Christopher B. “Jouett I (Destroyer No. 41).” Naval History and Heritage Command. 2017-12-05. Retrieved 2023-06-06. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/j/jouett-i.html

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Baber. “REAR ADMIRAL JAMES E. JOUETT: A Distinguished Kentuckian and a Heroic Naval Officer.” 11.

[viii] Ibid, 11, 12.

[ix] Baber. “REAR ADMIRAL JAMES E. JOUETT: A Distinguished Kentuckian and a Heroic Naval Officer.” 10.

[x] Havern Sr. “Jouett I (Destroyer No. 41).” Naval History and Heritage Command.

[xi] Browning Jr., Robert. M. “’Go Ahead, Go Ahead’: With the Battle of Mobile Bay’s outcome hanging in the balance as his squadron’s ships quickly piled up before Confederate Fort Morgan’s blazing guns, Rear Admiral David Glasgow Farragut coolly took a gamble that earned the Union Navy a dramatic victory.” Naval History Magazine, Vol. 23, no. 6. July 2014. Accessed 07-08-2023. https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2009/december/go-ahead-go-ahead

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Browning Jr., Robert M. “’Damn The Torpedoes’: What did Farragut Really Say at Mobile Bay? In the wake of battle, accounts varied, and speculation continues to this day”. Naval History Magazine, Vol. 28, no. 4. July 2014. Accessed 06-07-2023. https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2014/july/damn-torpedoes#footnotes

[xiv] Browning Jr., Robert. M. “’Go Ahead, Go Ahead’”.

[xv] Browning Jr., Robert M. “’Damn The Torpedoes’”

[xvi] Browning Jr., Robert. M. “’Go Ahead, Go Ahead’”.

[xvii] Baber. “REAR ADMIRAL JAMES E. JOUETT: A Distinguished Kentuckian and a Heroic Naval Officer.” 14

[xviii] Ibid

[xix] Patrick Murphy, U.S. Civil War – U.S. Navy. Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Accessed 07-07-2023. https://www.cmohs.org/recipients/patrick-murphy

[xx] Baber. “REAR ADMIRAL JAMES E. JOUETT: A Distinguished Kentuckian and a Heroic Naval Officer.” 14.

[xxi] Browning Jr., Robert. M. “’Go Ahead, Go Ahead’”.

[xxii] Havern Sr. “Jouett I (Destroyer No. 41).” Naval History and Heritage Command.

[xxiii] “Rear Admiral Jouett Dead.” The New York Times. 1902-10-02. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

[xxiv] “Jouett A Fighter.” Goodland News. 1898-07-09. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

[xxv] “Rear Admiral Jouett Dead.” The New York Times.

Thank you for this!