The 1889 Seattle Fire and the Grand Army of the Republic

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome back Richard Heisler of Civil War Seattle

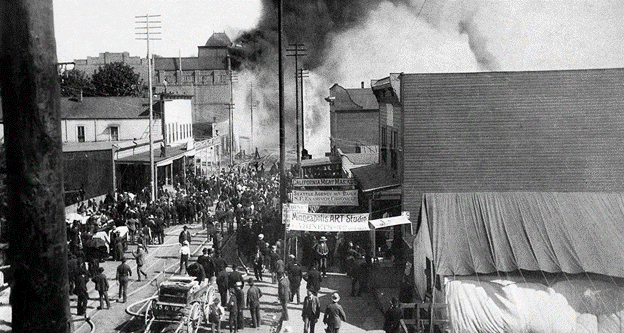

It all started with a pot of glue. On the afternoon of June 6, 1889, in a basement-level cabinet shop of the Pontius building at the southwest corner of Seattle’s Front and Marion streets, a small pot of boiling glue overheated and burst into flames. When workers in the shop attempted to extinguish the initial fire, cold water was mistakenly tossed onto the glue pot. As a result, the burning mess exploded, and the flames rapidly spread to the surrounding sawdust and shavings. Soon the blaze erupted beyond the shop and consumed the building, beginning an urban conflagration that burned nearly 120 acres of Seattle’s central business district.

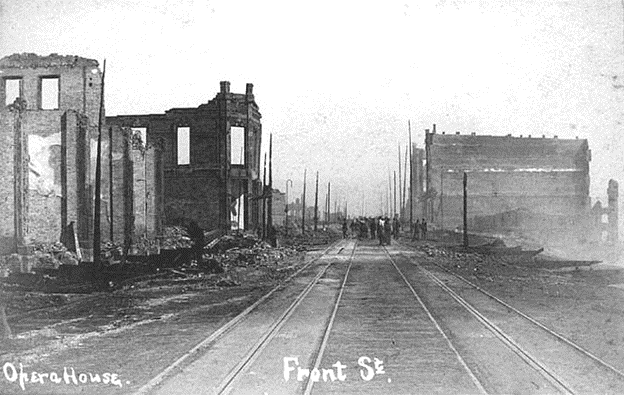

Remarkably, no loss of life occurred during the fire, but the property damage was immense. Twenty-five blocks of the city burned to the ground. For Seattle, it was a dramatic turning point in the young city’s history. Like the proverbial Phoenix rising from the ashes, the emerging city of Seattle redesigned and rebuilt the heart of the city from the ground up.

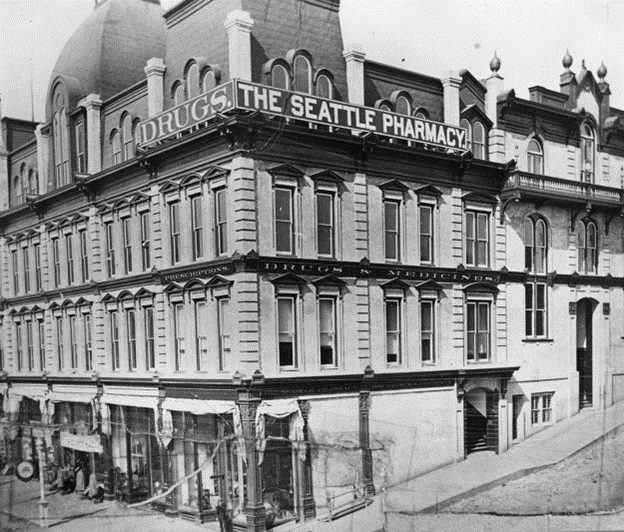

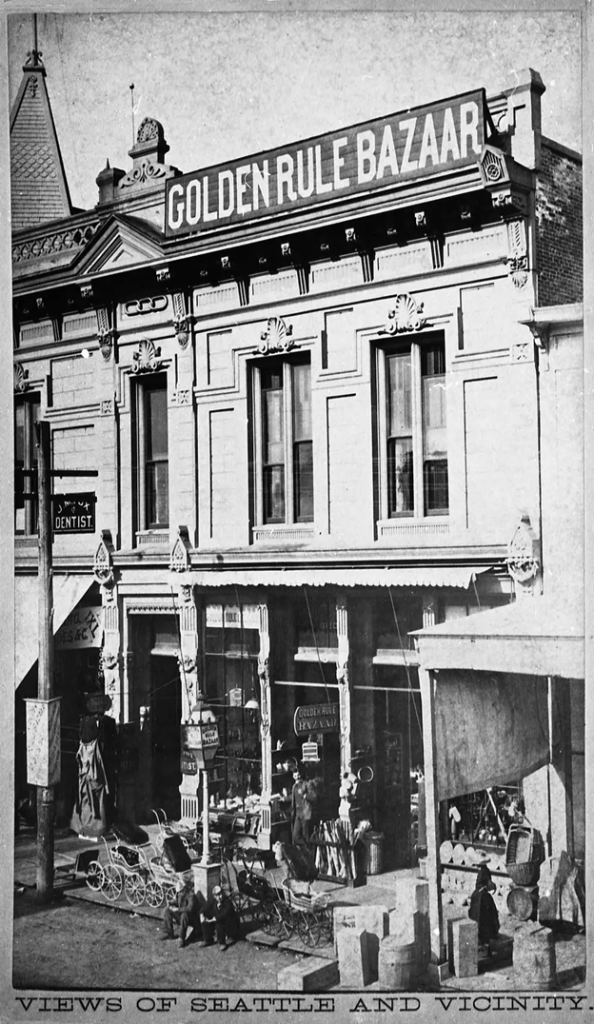

Just across Front Street from the Pontius building where the Great Fire erupted was the recently constructed Frye Opera House, built in 1885 as the most expensive building in Seattle’s history at the time. The building was home to the John F. Miller Post No. 31, Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.). Established in 1886, the Miller Post was the second G.A.R. post in the heart of the city, formed to accommodate the city’s rapidly growing population of Union veterans. Seattle and Washington Territory’s first G.A.R. post, the Isaac Stevens Post No. 1, established in 1878, had its post hall in the Reinig Block, neighboring the opera house across Marion Street just to the south.

Both buildings were clad or constructed with brick or stucco, providing some initial hope of serving as a barrier to limit the fire’s spread. Those hopes were quickly dashed, as flying cinders ignited flames on the roof of the opera house. Flames then spread into the timber framing, and soon the structure was consumed by the inferno and collapsed. Moments later, the Reinig block suffered an identical fate and was also destroyed in mere moments. It was then apparent to all that an immense amount of destruction to the city was imminent.

With the destruction of the opera house and the Reining block, Seattle’s two leading G.A.R. posts suffered tremendous loss. Although many businesses whose buildings were lost later in the fire had enough time to remove important materials, belongings or merchandise, this was not the case for Seattle’s Grand Army posts. The destruction of both posts’ property was complete. Nothing remained but ash. The posts’ furniture, records, documents, photographs and war relics vanished in an instant, irreplaceable treasures lost to history in an instant. While Seattle rebuilt and toward the future, a segment of the nation’s Civil War history was lost forever.

The nation’s leading Union veterans’ publication, the National Tribune, described Seattle’s devastation to the nation’s old soldiers just a week after the fire. “There is great privation among the poor classes,” the Tribune proclaimed, “The streets are crowded with people wandering about penniless and homeless.” A proclamation from Washington State’s governor was included, saying in part, “The city of Seattle is in ashes…Thousands of her citizens are without food and shelter. Neither can subdue the spirit of her people.” The governor continued, stating “She will rise again in her desolation. She is not a supplicant, but there are homeless people to be sheltered and hungry ones to be fed.” He appealed to the “great-hearted people of our territory” to respond to the appeal to help their fellow Washingtonians.

In the wake of the destruction, the two neighboring G.A.R. posts initially moved along slightly different paths. The Stevens Post, well established and stable in its membership and finances by the time of the fire, fared the better of the two. The leadership and members of the Stevens Post sprung into action, undoubtedly with the assistance of many Miller Post men, to raise tents and created a relief station just north of the burned district to provide aid and assistance to their fellow veterans that were in need of any form of support in the immediate aftermath of the fire.

Three days after the fire, the “Work of Relief” had begun in earnest, and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer newspaper printed notice that “all veterans needing assistance” were invited to call at the tents raised at the orchard on the property of Seattle pioneer Arthur Denny at Front and University streets, four blocks from the ashes of the posts’ former homes. The needs of impacted veterans would be “promptly attended to” by the G.A.R., the paper stated. The Grand Army men acted in the interest of all of the city’s veterans, not just those who were members of the organization. Residents of Tacoma, amid that city’s relief efforts to be sent to its sister city, provided the G.A.R. tents in Seattle with “two double team loads and one single load of provisions” to benefit the veterans in need.

The National Tribune provided veterans across the nation with ways to assist. A 44th New York Infantry veteran, Washington State senator N. J. Parkinson explained that the Seattle posts, among “the strongest in the territory” had suffered severe loss with the destruction of the post rooms and property. He then explained that the post members also lost a “great deal individually, in the burning of their houses and places of business.” Some, he said, “were reduced to absolute destitution.” Contributions to help fellow veterans were welcome, and Parkinson instructed veterans from around the nation to direct their support to the Stevens Post commander, or J.R. Lewis, chairman of the relief committee. The Grand Army’s women’s auxiliary, the Woman’s Relief Corps, also lent support from around Washington. The Tribune pointed out that such situations “bring forcibly to mind the necessity of such works of mercy as that which the W.R.C. is engaged.”

While Miller Post members aided the Stevens Post in its relief work, the post as an organization was confronted with a less certain future. Although the post counted among its membership some of Seattle’s leading citizens, such as George Kinnear, Thomas Minor and William Latimer, its future was much murkier than that of the Stevens Post. In 1891, two years after the fire, William Latimer recounted the uncertain days of the Miller Post after the Great Fire. He spoke at an event commemorating the 25th anniversary of the establishment of the G.A.R. and lamented that the fire had “swept everything” from the post and that the effects of the “misfortune bore heavily for a time” on its members. “Having no place to meet, with little or no money in the treasury,” the situation greatly discouraged the men of the Miller Post.

For a time, the Miller Post held no regular meetings. Neither the Miller post nor the Stevens post sent delegates to the G.A.R. national encampment that August. A few of the more faithful Miller Post members maintained an effort to get together in private offices or residences. The post was faced with the choice of whether to “disband or go to work with redoubled diligence” to reestablish itself. Latimer described with pride how the post members took on the challenge of a new start, and “as the city of Seattle rose from the ashes,” so it was “with the John F Miller Post.” He continued, explaining, “we arose from our misfortune, took new life, and resolved that we would have a larger and better post than before.” The John F. Miller Post did just that and by December was again holding post meetings at the Young Naturalists Hall on the University of Washington grounds. A friendly rivalry emerged between the two posts. Between 1890 and 1891 the Miller post nearly tripled its membership, and by 1892 had shed its status as the “baby post” of the Department of Washington.

The Miller post continually built up its membership and maintained its place alongside the Isaac Stevens Post among the leading posts of the Grand Army of the Republic in both Seattle and Washington State. For decades after the Great Fire of 1889, the Union veterans of the Stevens and Miller Posts were a constant feature in the life of Seattle. Surviving members of the two posts lived in Seattle well into the 1940’s. Their unswerving commitment to the organization’s precepts of “Fraternity, Charity and Loyalty” and their perseverance in overcoming total loss in June 1889 ensured that Seattle’s Civil War legacy would endure.

Sources:

Caldbick, John. “The Great Seattle Fire Part 1” History Link. Sept. 19, 2020 https://www.historylink.org/file/21090;

“That Immortal Glue Pot” Seattle Post Intelligencer June 22, 1889 p. 4; “Miller Post GAR Will Attend” Ibid. Dec. 14, 1889 p. 8; “Attention GAR” Ibid. 24 Sep 1889 p. 3; “Attention Stevens Post” Ibid Jan 8, 1888 p. 5; “Attention Stevens Post” Ibid Jan 8, 1888 p. 5; “Grand Army of the Republic” Ibid. Mar 1, 1891 p. 13 “Memories of War” Ibid. Apr 7, 1891 p.8 “Seattle in Ruins” The National Tribune June 13, 1889 p.8 “Vets in the City” Ibid. July 11, 1889 p. 5 “All Along the Line” Ibid. Aug 15, 1889 p. 6

In the late 1960s when I was an undergraduate and graduate student at the University of Washington, even those of us who were intrigued by local history never heard anything about the Great Seattle Fire. Thank you for the walk down memory lane. The buildings may be gone but many of the streets are still present.

Thanks for this article. I had never heard of the fire and had no idea that such a significant building (the Opera House) stood at the corner of Marion and (today) First Ave,