Echoes of Reconstruction: New Sources for Examining Reconstruction and the War on Democracy

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome back Patrick Young, author of The Reconstruction Era blog.

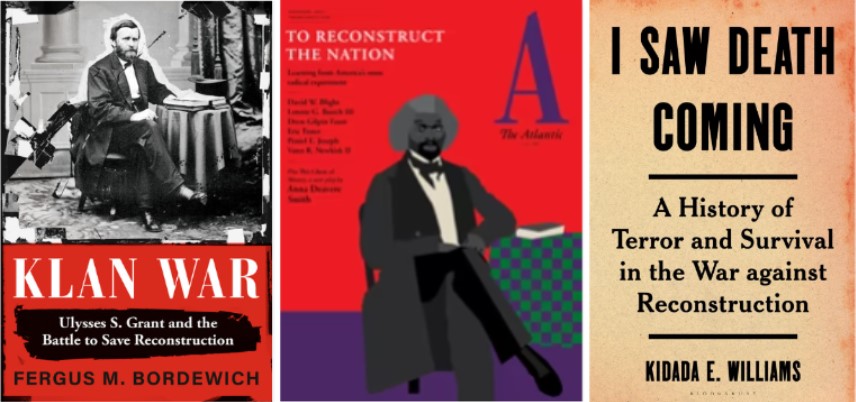

As I have in past years, this month I wanted to let you know about new sources to learn about Reconstruction. Two new books have arrived this year to tell the story of the war against Reconstruction, I Saw Death Coming: A History of Terror and Survival in the War against Reconstruction by Kidada E. Williams and Klan War: Ulysses S. Grant and the Battle to Save Reconstruction by Fergus M. Bordewich. Both books have attracted highest praise in book reviews and I Saw Death Coming was long-listed for the National Book Awards for 2023.

Imagine that someone was writing a history of the United States’s war in Iraq and it ended with the toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue on April 9, 2003. Sure, by then the conventional forces opposed to the United States military would have been defeated, but the history would have skipped the next two decades of conflict that really reshaped to the region. Well, that is how most histories of the Civil War end. Handshakes after the surrender at Appomattox without the messy guerrilla warfare that helped partially restore the old Confederate hierarchy to power.

“The War Against Reconstruction,” as Kidada Williams names this second phase of the armed Confederate struggle against the United States, was focused less on pitched battles with United States soldiers than on a week-by-week war on the freedpeople whose emancipation had been declared by the 13th Amendment in 1865. Black people had always been the targets of violence before the amendment, but after freedom, came retribution and restoration. As Kidada Williams writes, “But this was not merely a continuation; emancipation and Black people’s fight for legal equality changed everything, incentivizing the all-out war white southerners waged on freedom during the Reconstruction period.” White Southerners were not just fighting to keep control of the region’s primary labor force, they also wanted to deny to Blacks the ability to go to school, to worship freely, to vote, to hold office, to go to court, to enforce the laws. This was a period when slavery was ended, but an even greater threat was Black Reconstruction which saw African Americans as Constitutionally standing at the same heights as whites.

While many people who study this period believe that there are few African American records to consult to tell the freedpeople’s account, there are actually thousands of pages of testimony taken by a committee sent to hear what was going on in the South in 1871. This Congressional Joint Committee to Inquire Into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States looked into scores of cases of attacks on Black men, women, and children and had witnesses testify with cross examination supplied by Democratic Congressmen. This testimony was published by Congress as were the Republican and Democratic reports from the members of the committee. These primary sources form the basic research for I Saw Death Coming. Kidada Williams says in her book that “Targeted people’s testimonies provide a counternarrative to the stories we’re told about Reconstruction’s supposed ‘failure.’ Speaking with one voice, they said white southerners were not attacking Black people impulsively or defending themselves from Black violence, as former Confederates and their apologists claimed. They were purposefully waging war on Black people’s freedom.”

The book brings readers the immediacy of seeing the Klan raids through the eyes of their victims. Raids typically took place at night at the cabins housing Black families. After surrounding a home without warning, white men disguised in Klan guises burst in on the sleeping family. As children cowered in fear and babies cried, the mother and father tried to grasp what was happening. Should they fight, which might lead to the whole family being killed, or should they try to remain passive in which the man would suffer beatings or death, but in which the other members would survive?

While the terrorists were in disguise, the victims would often come to realize that they knew some of the attackers. Some discovered that a Klansman was a long-time acquaintance, or an overseer from slave days. Others were merchants they bought goods from, or coworkers on a large project. Not only were their bodies abused, the victims also found their sense of belonging to the same community as these white men was ill-founded.

While murder was carried out most often against Black men, rape was one of the ultimate punishments against Black women and girls. Rape had been employed for decades against Black women held as slaves before the Civil War. With freedom, Black women claimed bodily autonomy and the right to refuse rape. During the Civil War, the Union Lieber Code had been published by the War Department that established that Black women had the same rights as white women to object to forcible sexual intercourse. After the war, Southern men tried to override this Federal interference with the traditional right of white men to take a Black woman without her consent. But this was not just a matter of the Klansman’s desire for gratification. Rape was also used as a weapon of war against Black families and the Black community. Rape, as per Williams, “broadcast the sexual violability of Black women and girls in the white war on Black freedom, which could undermine family and communal unity.”

The women suffered, their male kin were humiliated by not being able to protect their women, and communal feelings were broken when babies were born out of these violent sexual violations.

In the immediate months after the Civil War ended, the defeated Confederates returned to their homes with a real concern about their fate. As the Spring of 1865 ended, most of them were offered an amnesty and the new legislatures in former Confederate states were elected by the same voters who had elected the legislators in 1860. The enemies of the United States were the voters in these Southern elections and these men decided to keep the allies of the United States from voting! In the months after Appomattox the Southern assemblies did not try to rebuild the physical infrastructure destroyed by war. Instead, they passed Black Codes designed to keep African Americans in a permanently subordinated position.

As Northern reaction to the widening swarth of repression began to take shape, the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the 14th Amendment, and other Reconstruction acts were passed by Congress to contain the outrages committed by Southern state governments against the freedpeople. With tight constraints put on the all-white state legislatures, armed bands started a violent campaign against Black people having an equal share in their states’ power.

By 1866, the Ku Klux Klan was already founded and in 1868 its terrorist tactics were widely reported on. Other groups took up its strategy and by 1871 hundreds of Blacks were being killed every year in the old Confederate states. Meanwhile, contrary to the impression many people have today, there were virtually no United States troops occupying the South after 1867. For example, South Carolina, in which the majority of people were Black, had grotesque incidents of racially-motivated violence from the Klan, yet the total number of Federal troops in the state was less than 500 men in February of 1871. Grant had seen the Democrats make political gains there and in neighboring North Carolina and Georgia as Blacks were frightened into staying home from the polls.

Klan War: Ulysses S. Grant and the Battle to Save Reconstruction by Fergus M. Bordewich tells a gripping tale of how President Grant responded to wage a counterinsurgency war on the terrorists who hoped to subvert democracy. Bordewich finds convincing sources from the time on the Klan’s attack on democracy, the administration’s plans to deal with the threat, and the Black community’s courageous help at the risk of their lives. This book is well worth reading.

Finally, I would like to suggest that you might want a shorter take on Reconstruction through the pages of The Atlantic Magazine for December 2023. This is a fresh-out magazine issue. The issue is titled “On Reconstruction” and all of the feature articles have to do with Reconstruction and the Civil War. Yoni Applebaum looks at how The Atlantic reported on Reconstruction in 1901 and how it followed the Dunning School of racist historiography. David Blight “annotates” Frederick Douglass’s essay “Reconstruction.” Drew Gilpin Faust looks at the men “who started the war.” Jordan Virtue tells the fascinating story of how Union General Adelbert Ames’s daughter (and Ben Butler’s granddaughter) kept correcting John F. Kennedy’s Lost Cause interpretation of Reconstruction in his book Profiles in Courage. Kennedy even tried to get George Plimpton, his critic’s grandson, to stop his grandmother from criticizing Profiles! Finally, Eric Foner gets down to why James Longstreet was the most hated Confederate general by other Confederate generals.

Thank you for bringing attention to these new works, especially I Saw Death Coming. Just in time to be added to Christmas book lists. The 1866 report of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction (which led to, inter alia, passage of the Fourteenth Amendment) also provided early evidence of the violent counter revolution taking place in the former Confederacy.

Thanks very much.

Definitely getting the latest Atlantic. Will be teaching reconstruction in the spring

Let us know what you think.

When I take a detour from the Spanish and Irish civil wars, these are on my list…

The Post-Civil War Civil War.

I am concerned about the sources cited by Bordewich. He asserts that Nathan Bedford Forrest became head of the Klan at a meeting which took place in the Maxwell House Hotel in Nashville in 1867 but the Maxwell House Hotel did not open for business until 1869. While the story of the Maxwell House meeting has been repeated many times by several writers there is no primary source documentation about this meeting. There is also a citation for an article which is said to have appeared in The Tennessean newspaper in 1868, but this paper did not begin publication until 1907. Finally, Bordewich asserts that in his testimony before the Joint Congressional Committee which investigated the Klan Forrest “admitted he was head of the organization.” Such an admission does not appear in the records of the Committee.

A topic of such importance needs careful documentation.