“To Hell or Richmond”—By Way of Alexandria

ECW welcomes back guest author Paula Tarnapol Whitacre

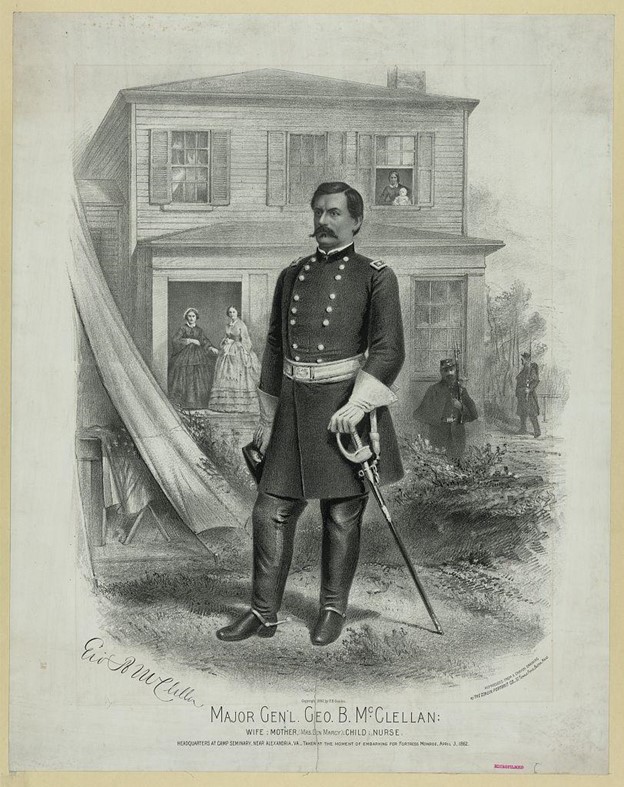

In their recent Emerging Civil War book on the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, To Hell or Richmond, Doug Crenshaw and Drew Gruber describe “one of the largest operations launched by the Union in the Civil War.” General George McClellan devised an operation to transport the Army of the Potomac by water to Fort Monroe on a peninsula southeast of Richmond, and from there to advance by land to the Confederate capital. Success, he told President Abraham Lincoln, who had been pushing him to attack the enemy for months, would end the war. As Crenshaw and Gruber detail in their book, that didn’t happen.

Let’s rewind a bit. How did all those men and all that materiel get to the Peninsula to begin with?

Logistics

The numbers were immense. Over the span of a few weeks from mid-March to early April 1862, more than 121,000 men, 14,500 animals, 1,150 wagons, 44 artillery batteries, and 74 ambulances shipped south. Most left from the wharves at Alexandria, Virginia. The Federals already held Alexandria and used it as a supply and logistics center, but the Peninsula campaign was on a whole different scale. According to historian Stephen Sears, “nothing comparable to the movement of the Army of the Potomac to the Virginia Peninsula had ever before been seen in America. Nothing comparable would ever be seen during the four years of civil war.”[1]

In January 1862, McClellan had asked John Tucker, newly appointed as an assistant secretary of war, if “transportation on smooth water could be obtained to move at one time, for a short distance 50,000 troops” (ultimately, more than double that number were transported). Whether Tucker truly knew the answer, he responded he was “entirely confident” of the feasibility even though it far surpassed the capacity of the U.S. Navy. A month later, bids went out up and down the East Coast to lease commercial vessels of all sizes and types. Tucker reported the results:

- 113 steamers at an average price per day of $215.10

- 188 schooners, at an average price per day of $24.45

- 88 barges, at an average cost per day of $14.27

He not so modestly characterized the operation: “I respectfully, but confidently, submit that, for economy and celerity of movement, this expedition is without a parallel on record.”[2]

Impressions

First-person accounts reflect the impact of witnessing this massive movement. As his regiment made its way into Alexandria from a nearby encampment, Pennsylvania chaplain J.J. Marks described the scene: “The entire plain and hill-side were covered with armed men; great columns of soldiers, whose guns flashed in the light, moved under the eye. Here, on the right, in the meadows of the plain, were thousands of horsemen, their polished armor reflecting the sunbeams like hundreds of mirrors…. In the Potomac lay a thousand craft, of every form and sail. The bands of the various regiments added to the effect by playing the same tune; and often there was a grand burst of harmony rolling over the field and quickening every pulse as we listened.”[3]

Local landowner Anne Frobel recounted, “We went into town and found the whole world moving toward Richmond. The Potomac river from Wa [Washington] to the fort—as far as we could see was one solid mass of white canvas. You could only get a glimpse of the water here and there so thickly were the vessel boats, steamers, little and big, of all sizes and shapes, crowded-crowded-packed together.”[4]

George Custer, later of Little Bighorn fame, sat along the waterfront as a 22-year-old lieutenant recently assigned to Gen. McClellan’s staff. The clatter of soldiers, cargo haulers, and wharf workers surrounded him. Horses and wagons went back and forth from warehouses to the ships. He wrote a letter to his parents that he would join “the greatest expedition ever fitted out is now going South.” He enclosed a copy of McClellan’s message to the soldiers of the Army of the Potomac in which his hero promised “the period of inaction has passed.”[5]

Not everyone was impressed with, as Tucker reported, the “celerity of movement.” Obtaining the vessels was daunting, but so, too, was organizing their use. Confusion about how many people could fit on each vessel made the loading last for hours longer than necessary. General Samuel Heintzelman, appointed to command one of the four corps, fumed when he learned that soldiers had spent the night without shelter in cold dense fog and rain. The provost marshal ordered all city saloons closed, but alcohol still flowed freely. On March 17, journalist George Albert Townsend reported that “coming in to Alexandria to-night, the scenes were frightful. Groups of fallen men would be seen literally entangled with each other, hopelessly, insensibly, irretrievably drunk.”[6]

Reversing the Tide

With the mass exodus over, Alexandria became relatively quiet. A local store clerk named Henry Whittington, very much pro-Confederate, wrote in his diary that “we confess to a great pleasure in getting rid of them and we trust that when they leave us now, that we may never look upon them or upon their like again.” Anne Frobel again planted her farm’s fields and repaired its fences.

To Hell or Richmond and other accounts detail the progress, or rather lack of progress, of Gen. McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign. By July, the whole operation was put in reverse.

A few months made a world of difference between the high spirits going down to the Peninsula and the bedraggled return to Alexandria. New York private Robert Knox Sneden reflected the change in mood. Waiting his turn to board a steamer at Harrison’s Landing on the James River, he watched as “long lines of troops moved…to the dreary looking wharf and began embarking on steamboats appropriated for transportation to Alexandria.” Bands played and flags waved, but, he recalled, “our spirits were not as buoyant as when another much larger fleet, filled with expectant troops left Alexandria in March last, ‘on to Richmond’ then being the universal song.”[7]

Paula Tarnapol Whitacre contributed a chapter to the book Clara Barton: Civil War Humanitarian (NMCWM Press, 2022). In 2017, she published a biography of abolitionist Julia Wilbur titled A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time: Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (Potomac Books, 2017). She is currently researching a book that focuses on Alexandria, Virginia, during the Civil War and Reconstruction.

[1] Stephen Sears. To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign. New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1992.

[2] Tucker’s report on the operation is reprinted in George Armand Furse, Military Expeditions Beyond the Seas, Volume 2. London: William Clowes & Son, 1897.

[3] J.J. Marks. The Peninsular Campaign or Incidents and Scenes on the Battle-fields and in Richmond. Philadelphia: J.P. Lippincott & Co., 1864.

[4] Anne Frobel, The Civil War Diary of Anne S. Frobel edited by Mary H. and Dallas Lancaster. McLean, VA: EPM Publications, 1992.

[5] Quoted in T.J. Stiles, Custer’s Trials: A Life on the Frontier. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2015. McClellan’s order was widely reprinted in newspapers, e.g. New York Herald, March 16, 1862.

[6] G.A.T. in the Philadelphia Press

[7] Robert Knox Sneden, August 21, 1862. Reprinted in Eye of the Storm.

Thank you for the great post, Paula!

This point really stuck with me: “Nothing comparable would ever be seen during the four years of civil war”

By the end of the war, the Union army had turned into a massive and well-oiled logistical machine…but it’s even more impressive that they staged the move to the Peninsula just a year into the war.

The Confederate Government would like to thank General McClellan for his profound paranoia and ineptitude, leading to his misdirection of some of the Union industrial plant into it’s impoverished hands. Thanks dude!

From my perspective as a transportation officer in the 70’s,with experience limited to truck convoys on Tidewater highways, I am unable to fathom the enormity of this undertaking. I am in awe of the complexity of this unprecedented, massive logistical challenge.