Civil War Relic Hunting: Destroying American History

A few years ago, I made a research trip to Germany to walk in the footsteps of Prussian revolutionary and Union General August Willich with a German colleague. We enjoyed a hearty meal at the home of an American Studies professor in Freiburg. After the meal, our host presented us with lead musket balls he had picked up on the 1849 battlefield at Waghäusel in Baden. I was thrilled to receive an artifact with an intimate connection to the rebellions in the German states which I had spent so many hours studying.

We decided to replicate Willich’s march with Friedrich Hecker through the Black Forest to Kandern in April 1848, where the nascent revolution would suffer a crushing defeat near where the stone Dog Stable Bridge spanned a small creek.[1] We found the creek, but the bridge had been replaced by a modern culvert. After rooting in the creek bed for a few minutes, we found worked stone remnants of the demolished bridge. Despite my protest, my colleague grabbed a grapefruit-sized piece of bridge rubble and dropped it in his ruck sack. “This will make a perfect bookend in my office,” he exclaimed.

Both of my German friends have PhDs in History and procured their finds on private land. Neither site has been professionally excavated by trained archaeologists, nor is it likely that they will be in the future, given the limited resources available for such projects and the secondary historical importance of these battlefields. So, what’s the harm in taking a few souvenirs?

Many American Civil War enthusiasts and some historians collect artifacts from the war, including soldier’s letters, arms and armaments, uniforms, and various articles lost by soldiers in camp, on the march, or in battle. Most collectors are motivated by a desire to make a visceral connection to history and purchase artifacts from “reputable” dealers, often at large shows promoting Civil War heritage. Despite the best intentions of most buyers and sellers, the challenge is finding enough verifiable provenance to prove that such artifacts were obtained legally; that is, in most cases, from private land with owner permission and not from public land, where such activity is usually illegal. But relic hunting raises many ethical issues besides legal concerns.

Despite the rare instances of a metal detectorist stumbling upon a hoard of gold coins or some other buried item of outsized value, most relic hunters are hobbyists with an appreciation of heritage and a love of the hunt. Most successful hunters only share knowledge of their favorite digging spots with a few trusted comrades. Heaven forbid that some nosy government official, or perhaps worse still, a professional archaeologist, might discover their honey holes and attempt to put an end to their recreation. Distrust between these two constituencies runs deep in many areas. Not sharing important data about forgotten historical sites to possess artifacts is selfish and may deprive the larger community of important historical knowledge.

Relic hunting may not be a profitable enterprise, but it is backed by big money interests. The pandemic unleashed a flurry of outdoor recreational pursuits, including metal detection. The U.S. metal detector business was already a $724 million market in 2022 and is expected to grow to $1.2 billion by 2028.[2] Cable TV and YouTube are rife with shows documenting relic hunting by amateurs whose only training was how to swing a detector. Leading associations, like the 200-member Northern Virginia Relic Hunters Association have their own relic shows and are sponsored by American Digger Magazine alongside no less than three metal detector manufacturers. Their mission statement is: “to promote the study and preservation of the American Civil War through the location, identification, and preservation of military and related historical artifacts.” The NVRHA does attest to collaboration with archaeologists.[3] But are such associations really promoting Civil War history or merely the private acquisition, possession, display, and sale of artifacts?

The most serious issue with relic hunting is the destruction of the archaeological context to violently extract souvenirs. Stripping a site of artifacts or destroying features like fire pits and earthworks that can tell us so much is irreversible. The potential knowledge gained from proper excavation and professional interpretation is lost forever. The number of Native American sites that have been wantonly plundered for arrowheads, decorative pottery, and other artifacts, for example, is legion. With advanced technology and professional standards and methods, we have unprecedented opportunities to learn more about our past, but we often allow amateurs and hobbyists to destroy our history in the service of private benefit.

The professional archaeologists who raised and preserved the submarine H.L. Hunley in Charleston Harbor in 2000 represent a good example of a proper excavation to not only preserve the rare artifact, but through careful and professional archaeology, gain an understanding of the sinking itself and the fate of the crew.[4] Once all the spent balls and other finds are removed from a section of a Civil War battlefield, we have lost countless data points that could lend insights into the intensity and troop movements in that sector. The sterile artifact resides in a display case, labeled “Culp’s Hill,” telling us next to nothing. One archaeologist compares digging relics to taking a pair of scissors to a great book, removing the best quotes, then burning the rest of the book. Without the entire book providing context to the quotes, the words lose their meaning.

Some relic hunters argue that they are saving history by removing decaying artifacts from the ground, ignoring their context entirely. On some occasions, they are called in to assist in “rescue archaeology” on a site facing imminent development. But most all relic hunters are not trained conservators and their removal of fragile artifacts and subsequent exposure to air, light, and improper cleaning can destroy an item rapidly. Unless the site is threatened, it is better to leave artifacts in the ground with the context intact for future generations of professionals with better funding and technology to derive the real treasure from that site: the history associated with the artifact. But the urge to discover and possess is strong. How do we reconcile relic hunters and archaeologists, and leverage the notion that both groups are passionate about preserving history?

Matthew Reeves, director of archaeology and landscape restoration at the Montpelier Foundation in Virginia, believes that professional archaeologists need to do more outreach to bridge the divide with relic hunters, help them to engage in less destructive digging, and convince them to adopt best practices of proper archaeological investigation. In 2012, Matt began inviting metal detectorists to assist in property surveys aimed at discovering the material remains of Montpelier’s enslaved population on the grounds of James and Dolly Madison’s former plantation with considerable success.

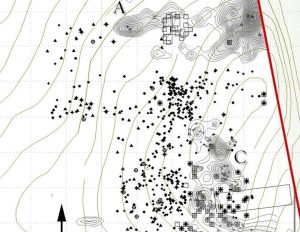

Scott Clark of Kentucky, an avid metal detectorist for more than 35 years, made a leap about twenty years ago from hobbyist to amateur archaeologist. He participated in the Montpelier program, learned various technological skills like GPS mapping, had his research published, and has spoken at archaeology and history conferences while maintaining leadership roles in the relic hunting community. Scott believes that archaeologists need to treat metal detectorists as potential allies instead of adversaries. He advocates bringing some of them to an “aha moment” when they recognize, for example, that a scatter chart of artifacts found and recorded in situ can tell a much larger and more valuable story than merely analyzing finds in isolation. The progression from finding a Confederate cannon ball to understanding the tactical choices of an artillerist in the heat of battle becomes much more rewarding and offers incremental understanding of that event.[5]

In 2020, Georgia Southern Anthropology professor Ryan McNutt led a project funded by the National Park Service designed to uncover the story of Sherman’s march in Southeastern Georgia. Students attended field schools and employed a range of techniques from high tech laser imaging to tried and true trowel scraping to identify geographical features associated with the war but since lost to history.[6] Perhaps a new generation of Civil War enthusiasts will learn to respect and conserve historical sites and support professional investigations rather than engaging in destructive digging. Then relic hunters might become an indispensable part of our history community, pursuing projects with learning in mind, instead of acquisition.

[1] David T. Dixon, Radical Warrior: August Willich’s Journey from German Revolutionary to Union General (Knoxville: Univ. of Tennessee Press, 2020), 46—8.

[2] 360 Research Reports, “Metal Detector Market,” accessed at https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/metal-detector-market-insights-research-report-ka2pf/.

[3] Northern Virginia Relic Hunters Association (website), accessed at https://nvrha.com/.

[4] Hunley (website), accessed at https://www.hunley.org/the-search-and-recovery/.

[5] Preservation Maryland: Old Line State Summit, “Can Relic Hunters and Archaeologists Work Together?” (2022) accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ybkbLCdeAWA.

[6] Georgia Southern University Newsroom, “Preserving History: Georgia Southern anthropology faculty, students to investigate Civil War battlefields,” May 29, 2020, accessed at https://news.georgiasouthern.edu/2020/05/29/preserving-history-georgia-southern-anthropology-faculty-students-to-investigate-civil-war-battlefields/.

Thanks for these thoughts, David. As a historic preservation professional, I agree with a great deal of it. Hobbyist metal detectors value history, but the way they often recover it means we cannot learn these lessons. Like you noted, there’s a dedicated corps of professional archaeologists using metal detectors, carefully noting the scientific information. Depth, soil makeup, exact pinpoint location, careful search methodology, etc. Metal detection can reveal artifacts that can change battlefield interpretation, locate camps and touching personal items, and tell human stories. But we need the data to be able to use them meaningfully!

I’d rather see 4 recovered artifacts with full GPS data than a whole case of things merely noting “Cold Harbor”.

In my observation relic hunting is more about thrill seeking and bragging rights than anything else.

Collectors or institutions who don’t prioritize the sharing of the knowledge and the material that they physically have are worse than worthless in the 21st century, they’re a liability. How much has been lost and will be lost when everyone is attached at the hip to technology capable of copying and sharing information on everything?

Nobody thinks you’re cool when you pass away and your estate sale turns up priceless photographs that nobody knew existed. I used to work for a guy clearing out homes for families, 95% of it goes in the trash. It’s amazing how many older folks never even made a plan.

With respect, I have to disagree. I believe one group that is often overlooked is the developers. Many artifacts have been lost to time due to urban sprawl and the building of apartments, homes, etc.

I myself am a hobby metal detectorist. I have found many civil war artifacts over the years. More importantly I have recovered civil war artifacts from locations that are now completely developed. If I didn’t dig those artifacts they would be gone forever.

I document each find with GPS coordinates to ensure the provenance of each find is preserved. I will one day donate all of my finds to a local museum so that others can enjoy.

I think there needs to be more common ground between archeologists and metal detectorists. Both groups are never going away and I think it would be beneficial for both groups to find alignment where it makes sense. We all enjoy history and want to preserve it for others