The Establishment of Arizona Territory: A Confederate Territory in the Southwest

ECW welcomes back guest author Katy Berman

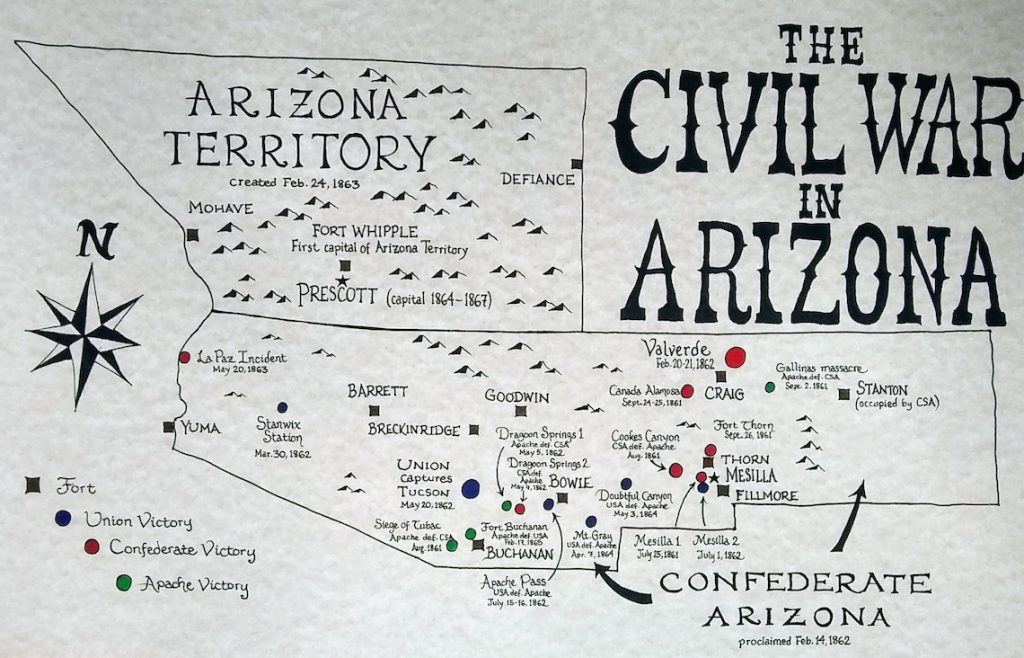

Amidst whoops and cheers, Lt. Col. John Baylor and his Texas regiment marched into the southwestern village of Mesilla on July 25, 1861. A week later, there was general rejoicing as Baylor established a provisional Confederate government in the Arizona Territory with Mesilla as its capital. An abundance of Southern sympathy existed in Mesilla. Most Anglos had come from southern states, and had voted to secede from the Union the previous March. However, the town’s elation was due, in part, to Baylor’s recognition of Arizona as its own territory, separate from the vast New Mexico Territory that stretched from Texas to California below the 37th parallel. [1]

The desire for its own territorial status had begun soon after New Mexico Territory was created from lands acquired from Mexico through conquest or the Gadsden Purchase. Congress approved the Gadsden Purchase in 1854, and United States troops replaced the Mexican garrison at Tucson on March 10, 1856.[2] By August, Gadsden Purchase residents were clamoring for a territory of their own. Three southern cities, Mesilla (the most populated), Tucson, and Tubac were separated from the territorial capitol of Santa Fe by a distance of approximately three hundred miles. Furthermore, a desert with the aptly forbidding name Jornado del Muerto (Journey of Death) lay between them. The absence of regular courts, a surveyor to provide necessary land titles, and a dearth of law enforcement were the chief complaints of Purchase inhabitants.[3]

A number of “memorials” or petitions for separate territorial status were presented to Congress by disgruntled inhabitants; the name “Arizona” was used for the first time in the 1856 document. President James Buchanan sympathized with the petitioners; in his 1857 State of the Union address, he urged Congress to create Arizona Territory.[4] In 1858, he was more forceful: “The population of that Territory, numbering, as is alleged more than 10,000 souls, are practically without a government, without laws and without any regular administration of justice. Murder and other crimes are committed with impunity.”[5] Congress was, perhaps, battle-scarred after the Kansas-Nebraska fiasco and refused to act. The problem of slavery forestalled any discussion of a new territory.[6]

The president tried a third time in 1859, reminding Congress that the people of Arizona, routinely subjected to “murder, rapine, and other crimes” were deserving of a territorial government.[7]

On April 5, 1860, thirty-one Tucsonans, wearied by the apathetic response from their government, decided to secede from New Mexico Territory and form the Provisional Government of Arizona.[8] Lewis Owings, as governor, tried to meet the needs of his constituents, chiefly protection from Apache raids. Elections continued to be held for delegates to plead Arizona’s cause in Washington, and on November 6, Edward McGowan became Arizona’s delegate to Congress. He had some success: HR 890, to provide a temporary government for the Territory of Arizona, was put before the House on December 18, 1860. Two days later, South Carolina seceded from the Union, and the bill languished on Capitol Hill.[9]

McGowan had been given instructions that, in the case of secession, he should ask the southern government for territorial status. Mesilla and Tucson had already held “secession” conventions, making it known that they wanted to align with the Confederacy. In Santa Fe, however, Governor Abraham Rencher, a native North Carolinian, assured President Abraham Lincoln of New Mexico’s loyalty. In a letter addressed to Secretary of State William H. Seward, dated April 20, 1861, Rencher stressed that “the people of Santa Fe are a law-abiding people, and loyal to the union; the governor, I well know, never expressed or entertained any other sentiment.”[10]

After Texas’ secession on March 2, 1861, a newly formed state legislature created the Committee of Public Safety to defend the Texas frontier; nineteen federal forts that had previously provided protection had been evacuated after secession. McCulloch brothers Benjamin and Henry and John “Rip” Ford were made colonels and asked to form regiments; Baylor served as lieutenant colonel to Ford.[11]

Baylor, an Indian fighter and former member of the Texas Legislature, was given the task of defending west Texas from potential incursions from U.S. troops still in New Mexico.[12] He had previously occupied El Paso and Fort Bliss, and made plans to march on Fort Fillmore across the Texas-New Mexico border. Historians differ over whether or not he had the authority to go on the offensive; however, he went ahead.[13]

Baylor may have heard a rumor that U.S. troops were approaching the border, or perhaps he was ambitious. He crossed the border and planned a surprise attack on Fort Fillmore commanded by Maj. Isaac Lynde, forty miles into New Mexico. When one of his troopers deserted and revealed the plot to Lynde, Baylor backtracked to Mesilla with his 258 men. He was challenged the next day by Major Lynde and approximately 700 soldiers of the 7th Infantry. Baylor’s small army, assisted by townsmen, drove off the Federal forces, perhaps because it appeared to Major Lynde that he was greatly outnumbered. Hedecided to evacuate Fort Fillmore and take his forces through the San Augustin Pass to Fort Stanton. Baylor caught up with them at the pass, and Lynde quickly surrendered, much to the regret of his junior officers.[14] The triumphant 2nd Texas Mounted Cavalry returned to Mesilla, where Baylor made his proud announcement on August 1. Additionally, he declared himself governor of the Confederate Territory of Arizona.

On August 8, Baylor wrote to Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn, CSA, commander of the Department of Texas, describing what he had accomplished and arguing for the necessity of reinforcements. His forces could not possibly repulse U.S. troops that were sure to arrive.[15]

The man for the job was Maj. Henry Hopkins Sibley who had resigned his commission in the U.S. 2nd Dragoons in April 1861. He had subsequently gone east to convince President Jefferson Davis to authorize an invasion of New Mexico Territory.[16] Sibley had served under Major Lynde during the Navajo Campaign in New Mexico only a year before.[17] He knew the region well and saw the potential for a passage through the territory to the port cities and goldfields of California.[18]. Davis commissioned Sibley as a brigadier general, instructed him to raise infantry, cavalry, and artillery regiments in Texas, and gave him the task of clearing all federal forces from New Mexico.[19] With that accomplished, taking possession of the five Mexican border states became an intriguing possibility.[20]

Awaiting Sibley at Mesilla, Baylor entertained an even more illustrious figure: Albert Sidney Johnston, on his way east from California.[21]. Baylor asked Johnston to take temporary command of his small army to which Johnston acceded, remarking to an aide that, “it was like being asked to dance by a lady-he could not refuse.”

General Sibley arrived at Fort Bliss in December 1861 and took command of all Confederate forces in New Mexico and Arizona.[22] He confirmed Baylor as civil and military governor of the territory. On December 20, he issued a proclamation to the people of New Mexico, taking possession for the Confederacy, and assuring them that he came with friendly intent.[23]

Back in Richmond, Baylor’s fame had caught the attention of War Secretary Judah Benjamin; in a letter to his chief, Benjamin wrote, “All the proceedings of Col Baylor appear to have been marked by prudence, energy, and sagacity, and to be deserving of high praise.”[24] Sibley’s words and Baylor’s actions proved persuasive. On January 18, 1862, the Confederate Congress passed the Organic Act, formally creating the Confederate Territory of Arizona. It was signed and put into full force by Jefferson Davis on Feb. 14.[25]

Arizona Territory, aligned with the Confederacy, did not have a long history, but it was governed effectively. Governor Baylor, in his initial proclamation, had divided the territory into two judicial districts, and by August 8, 1861 a probate court sat in the capital of Mesilla. Baylor retained some government officials and appointed others, among them a tax collector, sheriff, overseer of markets and special road commissioner, and pound keeper. Laws were passed, such as the forbiddance of butchering animals or rendering lard on public thoroughfares. Taxes were collected on balls, fandangos, and “All Carts & Wagons of Produce From Texas or Mexico.”[26]

An intimation of Confederate reversals is revealed in the Mesilla court records. On May 5, 1862 it was noted that the court would be suspended until June 2 because of “disturbances in the state.” On June 2, the court was adjourned until the next term. Turning the page, the records then read, “UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, TERRITORY OF NEW MEXICO, COUNTY OF DONA ANA, APRIL 8,1863.” [27]

Sibley’s Brigade, despite its considerable successes, had come to grief after the battle of Glorietta Pass when its supply train was attacked by Union forces. It was the end of Sibley’s crusade to the California coast.[28] Baylor’s forces were not large enough to hold Arizona by themselves.

The Confederate invasion of the Southwest did compel the United States to take Arizonans seriously. Colonel James H. Wright, commanding the Southern District of California, was ordered to lead an expedition to open the southern mail line and recapture forts in Arizona and New Mexico.[29]

The “Column of California,” under Brig. Gen. James H. Carleton, left Fort Yuma, California on April 28, 1861. By June 8, Carleton had established his headquarters in Tucson, where he issued a proclamation: “To all it may concern: The Congress of the United States has set apart a portion of New Mexico, and organized it into a Territory complete by itself. This is known as the Territory of Arizona.”[30] Less than a year later, the House endorsed the Organic Act establishing the Territory of Arizona on May 8, 1862. Lincoln signed it into law the following February.[31]

Confederates never relinquished the hope of retaking their sole territory. A government in exile, headed by Davis appointee Robert Josselyns sat in San Antonio, Texas until surrender. Plots were hatched, raids were conducted, but control of the territory was irretrievable.[32] For all intents and purposes, it was now the United States Territory of Arizona, but it was Arizona Territory, forevermore separate from New Mexico.

Katy Berman is a retired elementary-school teacher residing in New Jersey. She earned her Bachelor’s Degree in English at the University of California, Berkeley and her Master’s in American History through American Military University. For several years, she has reviewed books for “The Civil War Courier.”

[1] Charles S. Walker, “Cause of the Confederate Invasion of New Mexico,” New Mexican Historical Review, 8, no.2:90. Accessed Feb. 7, 2024, https.//archive.org.

[2] Johnny D. Boggs, “The Road to Statehood, Southwest Style” Historynet, 8/18/1017. Accessed February 7, 2024, https.//ww.historynet.com.

[3] L. Boyd Finch, Confederate Pathway to the Pacific (Tucson: Arizona Historical Society, 1996), 25.

[4] James Buchanan, “First Annual Message to Congress on the State of the Union,” Dec. 8, 1857, The American Presidency Project, Accessed Feb. 7. 2024,https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu.

[5] James Buchanan,”Second Annual Message to Congress on the State of the Union, Dec. 6, 1858, The American Presidency Project, Accessed Feb. 7. 2024,https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu.

[6] A political history of Arizona, Confederate Pathway to the Pacific, pg37

[7] James Buchanan, “Thirds Annual Message to Congress on the State of the Union,” Dec. 19, 1859. The American Presidency Project, Accessed Feb. 7. 2024,https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu.

[8] Finch, Confederate Pathway to the Pacific, 36.

[9] The Far Southwest, 146-1912: Territorial History of Lincoln’s NM Patronage: Saving the Far SW for the Union by Deren Earl Kellogg.

[10] Calvin Horn, New Mexico’s Troubled Years: The Story of the Early Territorial Governors (Albuquerque: Horn and Wallace, 1963),87. Rencher appears to be referring to himself. Forward by John F. Kennedy!

[11]Steve Cottrell, The Civil War in Texas and New Mexico, (Gretna: Pelican Publishing House, 1998),16. “John “Rip” Ford earned his nickname by writing R.I.P. at the bottom of casualty lists during the 1846-48 Mexican War.”

[12] Ibid., pg. 22

[13] Meghan Kate Nelson, “How the Civil War began in the American Southwest.” by Meghan Kate Nelson April 16,2020. Accessed Feb. 7, 2024, The National Endowment for the Humanities (neh.gov). Cottrell, The Civil War in Texas and New Mexico, pg. 22.

[14] Ray Colton, The Civil War in the Western Territories: Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1959), 15-16. Accessed Feb. 7. 2024, https.//www.internetarchive.org.

[15] F. S. Donnell, “The Confederate Territory of Arizona, From Official Sources,”, New Mexico Historical Review 17, no. 2, pg. 153-154.

[16] Martin Hardwick Hall, “Formation of Sibley’s Brigade and March to New Mexico,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 61, no, 8,pg. 385-86. Accessed Feb. 7, 2024, https://www.internetarchive.org.

[17] Jerry D. Thompson, Henry H. Sibley, Confederate General of the West,(Natchitoches: Northwestern State University Press, 1987), 175.

[18] Hall “Formation of Sibley’s brigade,” pg. 387.

[19] Ibid 218. “Cause of the Confederate Invasion of New Mexico” by Charles S. Walker, pg. 76.

[20] Walker, “Cause of the Confederate Invasion of New Mexico,” pg. 83.( Walker argues that possession of the Southwest in order to persuade European governments to recognize the Confederacy was the chief reason behind the Confederate invasion of New Mexico).

[21] Finch, Confederate Pathway to the Pacific, pg. 82.

[22] Hall, “Formation of Sibley’s Brigade,” pgs. 401-402.

[23] F. S. Donnell, “The Confederate Territory of Arizona, From Official Sources,”, New Mexico Historical Review 17, no. 2, pg. 155.

[24] Ibid, pg. 157

[25] Thompson, Henry Hugh Sibley, pg. 238.

[26] Charles Walker Jr., “Confederate Government in Dona Ana County: As Shown in the Records of the Probate Court, 1861-62,” New Mexico Historical Review 6, no. 3, pgs. 258, 263, 283,

[27] Ibid., pg.302.

[28] Colton, Civil War in the Western Territories, 96-97.

[29] Transcribed by Kathy Sedler, “G. Wright, Brigadier- General, U.S. Army, Commanding to Brig.-Gen. L. Thomas, Adjutant-General, U.S. Army, Washington D.C., December 23, 1861.” , Records of California Men in the War of the Rebellion,Militarymuseum.org.

[30] Sedler, Records, G. Wright, Brigadier-General, U.S, Army Commanding, Headquarters, Department of the Pacific, San Francisco, June 28, 1862.

[31] Wagoner, Arizona Territory, pg..vii.

[32] L. Boyd Finch, “Confederate Schemes to Recapture the Far Southwest,” The Journal of Arizona History, 33, no,1 (Spring, 1992), 59.

Katy Berman

Excellent article!

If I may make a couple of minor additions:

Mesilla was important as a significant crossroads: the ancient Royal Road connecting Mexico City to Santa Fe – called Camino Real de Tierra Adentro – ran north through Mesilla, where it intersected the newly established (1858) Butterfield Stage Route, which ran west to Los Angeles.

The proposed Southern Route for the transcontinental railroad (advocated by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis in 1855/56) would have approximated the course of the Butterfield Stage Route… although instead of reaching the Pacific Ocean near Los Angeles (the existence of the Free State of California making that impossible after 1861) it appears to have been envisioned to “take territory” in Sonoma or Baja California and make the Pacific Ocean connection in that way.

All the best

Mike Maxwell

thanks Katy … like most Civil War buffs, I knew the military history … your political history completes the picture … nice job!

Thank-you Mike and Mark for your nice comments!