A Mother Trades Her Under-age Son for Cold, Hard Cash

When her under-age son decided to join the army soon after Gettysburg, a Maine mother faced a life-changing decision. She chose wrong.

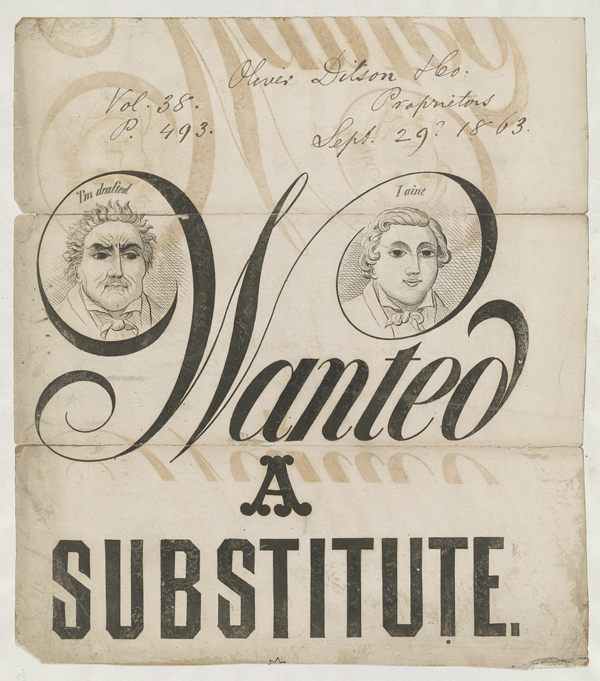

A 23-year-old “factory hand” in June 1860, William M. Lavery had risen to “superintendent” when he was drafted at Augusta, Maine on July 14, 1863. He offered an employee, “laborer” James Edward Davis, $325 to be his substitute.

Admittedly only “seventeen years and seven months of age,” Davis agreed to the deal. Passing the physical examination conducted by Dr. C. A. Wilbur in Augusta on July 27, Davis confirmed his age and substitute status to the provost marshal, Capt. Andrew D. Bean, and enlisted that same day. The three-member Board of Enrollment signed off on the enlistment, despite Davis being a minor.

The $325 “fell into the hands of his mother,” Mrs. Delilah Baldwin, a newspaper correspondent reported. Twenty-four years younger than her son’s father, James Davis, she had remarried after his recent death.

Standing 5-4½, James E. Davis had hazel eyes, brown hair, and a sandy complexion when he mustered on July 31. Pocketing the substitute payment, Delilah Baldwin promptly filed a writ of habeas corpus asking that her son be discharged because he was not yet 18.

Judge Asher Ware presided at the hearing held at the U.S. District Court in Portland on Monday, August 3. Baldwin insisted the army release her son. Sifting through the evidentiary paperwork, Ware directed Baldwin to prove Davis’ age from Augusta’s municipal records. If Davis was a minor, Ware would order him discharged, but Baldwin must return the $325 to Lavery.

Baldwin “did not see it in this light. She wanted the money and her son too,” the correspondent noted. Ware told her that she could not have both. She made her decision “after some considerable humming and hawing.”

Baldwin decided “that, as she had got the $325,” she “would get $200 more” in federal and state bounties, “and moreover would receive the monthly pay of her son.” So “she would let him go, as it was more than he could earn at Augusta by his work,” the correspondent wrote. Delilah Baldwin took the cash, “withdrew her petition, and gave her consent” for Davis to enlist.

According to one state and one federal record, he went to Co. C, 16th Maine Infantry Regiment. However, only one James Davis appears on the regimental rolls: 24-year-old draftee James Davis of Portland, who stood 5-11¾ and also mustered into Co. C on July 31, 1863 — but in Portland.

Neither Davis lasted long in military service. His death certificate indicates that 18-year-old James E. Davis was “shot” dead at “Spottsylvania” on May 1, 1864. Private James Davis was “killed in action” at “Spottsylvania, Va.” on May 8.

Delilah Baldwin filed a mother’s pension application for her son, James Davis (no middle initial listed), on June 29, 1864. She went after a government pension only weeks after her boy went into a Virginia grave. She had already proven that she thought cold, hard cash was worth more than her son.

Sources: Habeas Corpus Case, Portland Daily Press, Wednesday, August 5, 1863; 1860 U.S. Census for Augusta, Maine; James E. Davis substitute volunteer enlistment form, Maine State Archives; James Davis Soldier’s File, MSA; James E. Davis death certificate, Maine Vital Records; Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Maine, 1864 and 1865, Stevens and Sayward, Augusta, ME, 1865, Appendix D, pp. 406, 531; Delilah Baldwin pension application, No. 55724, U.S. Civil War Pension Index, Roll 113, National Archives

Just in time for Mother’s Day!

Fascinating story!

Why, why, why….Delilah???

The fact that I immediately “got” your Tom Jones song reference is actually oddly disturbing……..

Yikes.

When I was a kid, I heard a story that one of my father’s ancestors in New York State “bought” a substitute. Does anyone know how one could go about researching this? Thanks.

Wow, fascinating story with an unfortunate end. Great title too!

If it was such a noble cause, why did the Federal government have to pay bounties to get people to fight?

That’s a great question … here’s what George Washington said about the relationship between fighting for ideology and financial reward … the quote below is from GW’s letter to John Bannister, a Virginia delegate to Continental Congress … the letter was written in April 1778 while the army was at Valley Forge … GW, by the way, served without pay for the duration.

“ … Men may speculate … and talk of patriotism … they may draw examples of great achievements performed by its influence … but whoever builds upon it, as a sufficient basis, for conducting a long and bloody war will find themselves deceived in the end.

We must take the passions of Men and those principles as a guide, which are the rule of action … I do not mean to exclude the idea of patriotism … it exists and has done much in the present contest … but a great and lasting war can never be supported on this principle alone … it must be aided by a prospect of interest or reward … for a time (patriotism) may, of itself, push men to action—to bear much—to encounter difficulties … but it will not endure unassisted by interest.”

Mark Harnitchek: Thank you.

Yes indeed – Washington was talking about men achieving the right to vote, to determine their own fate, and to have what was most important to Americans in this period when the country was more than 90% agricultural – land of their own, which the average person in England was not allowed to own. All of this did not symbolize material wealth, but freedom and independence. Thus, these things, as well as monthly pay in order to handle personal expenses – which, by the way, Continental soldiers never received until years after the war ended, prompting some to come very close to full mutiny – were not payment as spoils of war, or to create mercenary soldiers, but to imbue each soldier with the concept that the individual American was important and part of the nation that was being created. In other words, it was an honest incentive.

But no bounties on top of monthly salary were paid in the Revolution, nor was there a draft. Eighty years on, the Federal Government was paying bounties to get men to enlist – mercenary money; had instituted a draft – which caused homicidal riots; and, perhaps worst of all, allowed rich men to avoid the draft – buying their way out of service by hiring substitutes. Not the stuff of Noble Causes! Last, don’t forget what Albert Sydney Johnston, in his address to his Army of Mississippi, called the Federal troops that his men were going to confront at Shiloh the next morning: Agrarian Mercenaries.

thanks Brian … how did you come across this story?

An excellent recent book on this larger topic is “Of Age: Boy Soldiers and Military Power in the Civil War Era by Frances M. Clarke and Rebecca Jo Plant. I highly recommend it.

Wow, maybe I wasn’t such a bad mother after all!