Artillery Hell

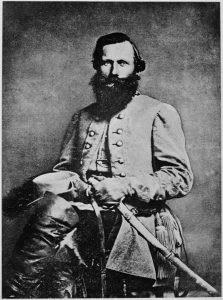

Imagine what must have gone through artillery Capt. Henry H. Carlton’s mind when he peered from the edge of the West Woods near Dunker Church toward the Federal lines on the morning of September 17, 1862. Leaving his battery behind, he rode in the company of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart of the cavalry to this spot. Looking out, the dead and wounded soldiers from both sides lay strewn across the fields. Visible to their right were the blue-clad infantry of Brig. Gen. George Greene’s division, and approximately 500 yards in front were “some two or three batteries of artillery on the ridge just opposite us.”[i]

Carlton did not know that Brig. Gen. Joseph Kershaw’s men had earlier driven Greene’s men from the West Woods and chased the Yankees into the open field beyond. Kershaw’s attack was supported by a battery, Capt. John P.W. Read’s Pulaski (Georgia) Artillery that had unlimbered not far from where Carlton now stood. A torrent of shell, shrapnel, and solid shot from the Union batteries opposite (Woodruff’s, Cothran’s, Knapp’s and a section of Tompkin’s) had blasted Kershaw’s men, forcing them to scramble back to the safety of the West Woods. One South Carolinian believed it was “one of the heaviest and most prolonged firing of shot and shell I can recall.”[ii] Read’s battery, in 20 minutes, had one gun disabled and 20 horses and 14 men killed or wounded. The battery “was so badly crippled that Read was forced to abandon his damaged piece and haul the three other guns off by hand.”[iii]

Carlton also did not know that it was Stuart’s idea to position him on this ground. Earlier, Stuart, thinking that he needed a battery to replace Read’s so the infantry could try another attack, rode to the rear. Why the army’s cavalry commander was directing things is a mystery. He found generals Jackson and McLaws together behind the lines idly talking. Stuart explained his need for a battery. McLaws, the division commander to which Kershaw, Read and Carlton were attached, said no. Jackson, without seeing the ground and outranking McLaws, told him to supply Stuart with a battery. Carlton’s battery, standing nearby in reserve, was chosen.[iv]

So there Carlton stood, not liking what he saw, as three guns of his battery approached through the woods. Carlton was an intelligent and experienced officer. The 27-year-old Georgian had graduated from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia and practiced medicine before the war. He had fought with his battery at Cheat Mountain, during the Peninsula Campaign, and at South Mountain, where he had lost one gun. He knew now his men were approaching a hornet’s nest.[v]

Yankee riflemen from Greene’s division had spotted them and began sniping at the Confederate officers. Both Carlton’s and Stuart’s horses were hit and Stuart’s courier killed by their fire. This did not deter Stuart. He instructed Carlton to place his battery at the edge of the woods “and not to let the loss of men and horses cause me [Carlton] to retreat from position but hold it” until Stuart could get infantry up. With that Stuart rode off.[vi]

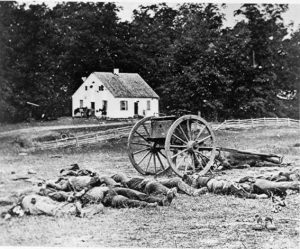

Bounding through the woods ahead of the guns was the battery’s mascot, a small dog named “Charlie.” As the guns arrived, Carlton shouted orders to unlimber. Before the artillerymen could swing the guns around, the Federal batteries (18 guns) zeroed in on them. Every horse pulling the limbers, plus some that were pulling the caissons were killed. A total of 18 horses died in a matter in a matter of minutes.

Library of Congress

Carlton’s crews struggled on, heroically hauling their three guns into position by hand. They rapidly opened fire, and in about 10 minutes they had fired off 109 rounds. The smoke was so thick that to assess the effect of this fire, Carlton stood exposed on the steps of Dunker Church. The Troup Artillery was simply outgunned – 18 guns to three guns. Despite their rapid rate of fire, one by one Carlton’s pieces were knocked out of action. He lost 30 percent of his men, with one killed and eight wounded.[vii]

When McLaws became aware of the destruction being wrecked on Carlton’s Battery, he ordered the captain to abandon his guns and pull what was left of his command back under cover. The battery accomplished nothing, except providing target practice for the Federal artillery. Carlton bitterly recalled years later that he had obeyed Stuart’s orders, “but at the sacrifice of my entire battery.”[viii] It was a useless sacrifice of the Troup artillery at Antietam.

————

Endnotes

[i] Carman, Ezra A., The Maryland Campaign of September 1862, Vol. II: Antietam, ed. Thomas G. Clemens, California, Savas Beatie 2012. Fn. P. 161H.H. Carlton to Ezra Carmen, May 20, 1893. Hartwig, D. Scott, I Dread the Thought of the Place: The Battle of Antietam and the End of the Maryland Campaign, Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press, 2023. P. 280

[ii] Carman, Antietam, fn. P. 204 & fn. 213. Lieutenant Y. J. Pope, 3rd S.C. to Ezra Carmen, March 20, 1895. Hartwig, I Dread the Thought, P. 279.

[iii] Hartwig, I Dread the Thought, p. 280. Read’s Battery consisted of 1 10-pound Parrott, 1 3-inch rifle, 1 6-pound smooth-bore gun, and 1 12-pound howitzer. He had 78 men total. P. 811 & Appendix C.

[iv] Ibid. Carman, Antietam, fn. p.235, McLaws letter to Heth, December 13, 1894.

[v] www.findagrave.com/memorial/7115166/henry-hull-carlton. https://civilwarintheeast.com/confederate-regiments/georgia/troup-georgia-battery/. Johnson, Curt & Richard C. Andrews, Jr., Artillery Hell: The Employment of Artillery at Antietam, College Station, Texas A&M University Press, 1995. P. 86. Carlton’s Battery consisted of 27 men and five guns – 2 10-pound Parrotts, 1 12-pound howitzer, and 2 6-pound smooth-bore guns. However, one gun had been disabled at Crampton’s Gap. Why Carlton only brought three of the four remaining guns is unknown. Johnson & Andrews postulate that Carlton’s 2 6-pound smooth-bores might have been left behind at Leesburg. If so, where Carlton got an extra cannon is unknown.

[vi] Carman, Antietam, fn. P. 186, H.H. Carlton to Ezra Carmen, May 20, 1893, December 2, 1899.

[vii] Johnson, Curt & Richard C. Andrews, Jr., Artillery Hell: The Employment of Artillery at Antietam, College Station, Texas A&M University Press, 1995. P. 86. Wise, Jennings Cropper, The Long Arm of Lee, Volume I: Bull Run to Fredericksburg, London & Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 1988. Bison Books edition, 1991. P. 321.

[viii] Carlton to Carmen, May 20, 1893 and December 2, 1899. Hartwig, I Dread the Thought, P. 281

Interesting. Two questions: (1) what was Stuart thinking; and (2) what happened to Charlie?

A fine piece on a dramatic day. Such is the story of Sharpsburg that one can take any part, any incident of the battle and find it was larger than life, dramatic, spectacular and horrifying. It merits a film.

Carman & Hartwig provide credible foundation for this tragic, nonsensical waste.

In answer to Kevin’s two questions, only Stuart himself could andwer what was going through his mind when he ordered the battery into action. Seems McClaws was the only sensible one. As far as Charlie’s story, I don’t know his fate. Glad you enjoyed the article.