The Civil War, Rocky Gorge, and the U.S. Forest Service

If a government agency can’t get the facts straight about the Civil War, who are you gonna trust?

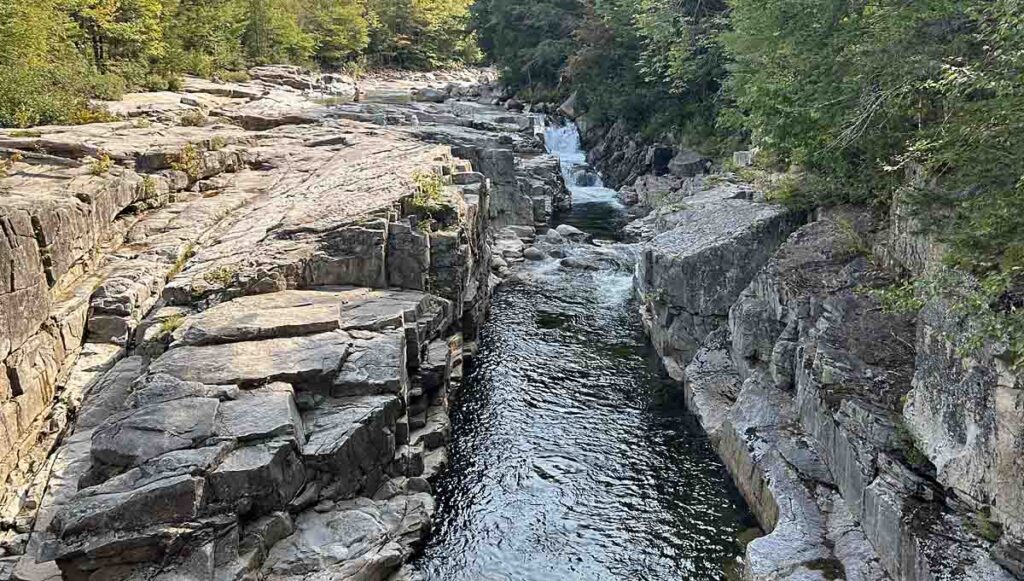

Tumbling eastward through the White Mountains for eons, the Swift River gradually wore a gorge through the bedrock granite where the river narrows west of modern Conway. Water tumbles over a 10-foot waterfall and flows into the magnificent gorge, officially named Rocky Gorge.

Accessible from the nearby Kancamagus Highway, the Rocky Gorge Scenic Area (so titled by the U.S. Forest Service) is a popular tourist destination. A walking path extends from the parking lot to the footbridge spanning the gorge. Upriver and downriver views from the bridge are excellent, and in low river flow, visitors explore the granite shelves along the Swift River’s southern bank.

“What has all this got to do with the Civil War?” you might ask.

Plenty, according to the Forest Service. Information panels scattered along the walking path explain how Rocky Gorge came to be. Its surface soiled by accumulated dust and plant matter, one such panel blares the headline, “Rocky Gorge: a favorite stop since the Civil War.”

All I saw was “Rocky Gorge” and “Civil War.” Neat! The gorge has a connection to the war!

It’s “when the railroads came to Conway,” the panel explains. “In 1864, the White Mountains became more accessible to tourists when the Boston & Maine Railroad brought its lines into Conway.” What was a “grueling three-day stagecoach journey from Boston became an easy four-hour train trip, with summer visitors flocking to the area …”

Figuring to write a blog post about the Boston & Maine, the Civil War, and Rocky Gorge, I arrived home several days later and started researching the connection between all three.

An issue arose: There is no such connection. No railroad reached Conway during the Civil War. The U.S. Forest Service has it all wrong.

Developers built two railroads to Conway after the Civil War. The Eastern Railroad Company built the Great Falls & Conway Railroad, which began at South Berwick and crossed the Piscataquis River into New Hampshire three miles away. In “a safe and very good condition” with “its equipment … in very good order,” this railroad had not yet reached Conway by 1870.

Neither had the Portland & Ogdensburg Railroad, for which “ground was broken” on September 7, 1869. Intended to snake through the White Mountains to connect with a railroad running east from Ogdensburg, New York, the P & O ran 33 miles from Portland to West Baldwin, Maine by 1870.

The 17-mile roadbed from West Baldwin to Fryeburg had been graded, and the 10-mile roadbed from there to Conway was “under contract.” The P & O should start running trains into Conway in 1872.

That’s eight years later than 1864, of course.

The Portsmouth, Great Falls & Conway Railroad reached Conway by 1875. The Portland & Ogdensburg Railroad had long since passed through Conway and Crawford Notch to reach “the Fabyan House,” a grand hotel built in 1873 in Carroll, New Hampshire. Fire destroyed the hotel in 1951, but its name lives on in Fabyan Station, the westernmost point to which the Conway Scenic Railroad operates today.

Intersecting at Conway, the two railroads carried tourists to and from the White Mountains and the region’s farm produce, lumber, and other products to Boston and Portland. Summer tourists and autumn leaf-peepers ride the Conway Scenic Railroad’s various excursion trains today, but no one arrives by train in Conway any more.

Where did the U.S. Forest Service get the date of 1864 for trains arriving in Conway? I don’t know. There was no Civil War blog post to write … but the research certainly was interesting!

Sources: Report of the Railroad Commissioners of the State of Maine for the Year 1870 (Augusta, 1871), pp. 5-6; Public Documents of Maine: Being the Annual Reports of the Various Public Officers and Institutions for the Year 1876, Vol. II (Augusta, 1876), pp. 20-21, 25

A nice catch.

And, “who are you gonna trust?” indeed. In its online entry on CSA General John Hunt Morgan, the National Park Service bluntly claims that Morgan was “murdered” after surrendering, specifically: “On September 4, 1864, after surrendering to a Union cavalry detachment near Greeneville, Tennessee, Morgan was murdered, perhaps in part to prevent him from escaping a second time.” https://www.nps.gov/people/john-hunt-morgan.htm#:~:text=On%20September%204%2C%201864%2C%20after,from%20escaping%20a%20second%20time.John Morgan.

As that is quite a bold statement, I recently asked the NPS what is the historical evidence upon which such a claim is made. The NPS is looking into the issue.

An update. The NPS, after reviewing the issue, recently revised its John Hunt Morgan entry. It now ends with: “On September 4, 1864, Morgan was killed near Greeneville, Tennessee, during a surprise attack by a US cavalry detachment.” See https://www.nps.gov/people/john-hunt-morgan.htm.

Just a suggestion: Interpretation signage must pass a review process, so inquire by requesting a copy of the application for the wayside and seek the sources used.