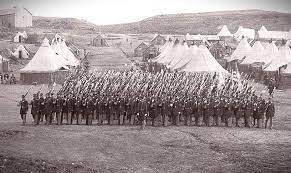

On the Road to Atlanta – Column of Division at Kennesaw

On June 27th, 1864, at Kennesaw Mountain, General William T. Sherman departed from his usual flanking tactics to try a frontal assault. Believing Confederate General Joe Johnston’s line was thin, the Federals believed that columns, rather than battle lines, would be the better tactical choice. In his memoir, General Oliver O. Howard insisted that they were the proper choice for the assault.

students of Napoleonic tactics have long debated the merits of column vs. line, or mass vs. firepower—supposedly best exemplified by the fight between French battalion columns and English lines. Unfortunately, much of this debate has been based on false assumptions, largely predicated by Sir Charles Oman’s misunderstanding of the tactics of the time. Oman theorized that the French foolishly clung to their battalion columns which were regularly shot to pieces by English battalions in line, delivering withering volleys into the hapless Frenchmen. While the French did customarily advance in battalion columns, they almost always attempted to deploy into line prior to the final attack; the English, far from simply receiving those attacks with firepower, usually instead delivered one short-range volley and charged with the bayonet—a completely different tactical equation that that which Oman theorized.

Why is this important? Because here we have another false assumption; that the Federals chose massed columns as a blunt instrument vs. Confederate firepower. General Howard, General Newton and their brigade commanders did not intend merely to send regimental columns over the works. Instead, they chose columns as the fastest way to approach the Rebel defenses without suffering unduly, also intending to deploy into line just before closing. They hoped that the Confederates would be surprised and thin on the ground, which is why speed was of the essence. Like the French, however, they miscalculated the difficulty in deploying, paying heavily for that miscalculation.

These columns, and how they were intended to be used, have been subject to considerable historical misinterpretation—not the least because General Howard’s description sounded as if the column was simply to run over the enemy works without stopping or deploying. In fact, everyone expected that the columns would deploy into regular battle lines once through the obstructing terrain and any man-made obstacles (abatis, downed brush, tangled wire, etc.) put in their path. Colonel Opdycke stated that his skirmishers should, “if not [able to take the works], pass over with [the assaulting columns] and protect their deployment.” Generals Wagner and Kimball were also provided precise in descriptions. Contradicting Howard (who stated the columns were “formed doubled on the center,”) Wagner formed his regiments “left in front,” while Kimball formed “right in front.” Lieutenant Andrew M. Potter, Adjutant of the 74th Illinois, was even more specific: “Close column by division, closed in mass on first division.”[1]

Grasping the significance of those details requires understanding Civil War regimental formations and drill. In line, the ten companies were not deployed in alphabetical order. Instead, they formed by seniority of captains, so that in case of losses, the most senior men would not all be on one flank. Thus, a regiment normally formed line in the following order, from left to right, as follows:

B G K E H — colors — C I D F A

Each two companies comprised a division: F—A (first division), I—D (second division), H—Colors—C (third division), K—E (fourth division), and G—B (fifth division). Which division formed the head of the column determined whether the division was formed “right in front” or “left in front.”

Right in front: Left in front:

F—A B—G

I—D K—E

H—Colors—C H—Colors—C

K—E I—D

B—G F—A

When it came time to go into line, a regiment formed “right in front” would deploy to the left, each two companies maneuvering successively to fall in on the left of F—A. Alternatively, if “left in front,” they would move to the right, forming successively on the right of B—G. Thus, Wagner’s regiments were to all swing to the right, filling the interval between his brigade and Harker’s, while Kimball’s regiments were to swing to the left, positioned to extend and protect Wagner’s left flank. Kimball subsequently reported that he tried to do exactly this, noting that the 74th Illinois deployed “within seventy yards of the enemy’s abatis.”[2]

At least two of the officers involved later expressed great dissatisfaction with the chosen formation, though admittedly with the benefit of hindsight. Col. Luther P. Bradley of the 51st Illinois contended that everything about “the assault on Kenesaw was a bad affair, badly planned and badly timed, and the formation of our column was about the worst possible for an assault on a fortified line.” Similarly, Nathan Kimball recalled that both “Harker and I . . . condemned the formation at the time. Newton said that such were our orders, and of course we obeyed and did the best we could. Such formations,” he continued, “have only the appearance of strength, but are really suicidal in their weakness.”[3]

[1]OR 38, pt. 1, 304, 335; A. M. Potter, “Kenesaw Mountain,” National Tribune, November 6, 1890.

[2]OR 38, pt. 1, 304, 335; see also Silas Casey, Infantry Tactics, for the Instruction, Exercise, and Manoeuvres of The Soldier, A Company, Line of Skirmishers, Battalion, Brigade, or Corps D’Armee. 3 vols. (Reprint. Dayton, OH: 1985), I: 3, II: 128-48. Many thanks are due to Chickamauga-Chattanooga National Park Historian James Ogden, Fort Oglethorpe, GA, for repeated discussions of these columns, how they were formed, and the details of “right in front” vs. “left in front.”

[3]Wagner, Organization and Tactics, 91.

Thanks for this interesting article! These were trained and/or experienced officers who planned and executed the attack you’ve described, and I’m frankly surprised they thought they it would be successful. The fast moving column sounds right, but then the more complicated and time-consuming deployment in the very face of an enemy firing line sounds pretty risky to me, given my impression of how much difficulty Civil War regiments often had with complex orders and movements. The May 10 1864 attack by column by Emory Upton and the May 12 1864 early morning attack by a Union Corps – both at Spotsylvania Courthouse – effectively broke the Confederate line and were at least initially successful. These attacks make more sense than what was attempted at Kennesaw 6 weeks later. Makes me wonder if the Army of the Potomac and the Army of the Tennessee communicated about these tactics in that 6 week period. Probably not, but it’s interesting to see the similarities in tactical planning for these attacks against entrenched Confederates.

As at Spotsylvania, the massed attack at Kennesaw Mountain failed. Why? Bad leadership!

It is interesting to note how attacks were formed and addressed 50 years hence, in World War I. Columns were only ever used in the opening weeks of the war; after that it was always lines, for two reasons – it would have been impossible to form columns in the trenches, or maintain them in the chewed up, shell-holed, muddy terrain. Both were constantly foiled by the same thing, though: modern firepower. In the early days of the war, the British Army in particular shot German columns or lines to pieces not with machine guns, which the high command was still not entirely reliant upon, but by the well-trained, fast, mass firing of the men’s Lee Enfield Mk. III rifles, whose magazines carried ten rounds. Trained to work the bolt of the rifle with thumb and forefinger and fire with middle finger, never bringing the weapon down from the shoulder except to push into the magazine two stripper clips of five .303 rounds, the Tommies poured out devastating fire and often had shell casings two or three inches deep at their feet.

Later in the war, it was discovered that direct fire at attacking lines was not nearly as effective as enfilade fire – using machine guns to direct heavy oblique fire into the sides of the attacking lines. The slaughter that resulted is difficult to apprehend even a century later.

I remember the mind numbing “close order drill”. Dave’s example brought back memories