James Dinkins, Belle Meade, and the Battle of Nashville

This post was written by Robert D. Cross, the chief historian at Belle Meade Plantation, with edits and additions made by Sean Michael Chick

On the morning of December 15, 1864, two great armies collided at Nashville. In the years that followed, the veterans from both sides recounted tales of heroism in the winter’s fighting, while the landmarks of the battlefield slowly faded away and urban development covered the battlefield.

By 1900, very few landmarks remained to suggest that any battle had taken place in Davidson County. Among those that survived was Belle Meade. Since its establishment in 1807, Belle Meade was one of the finest stock farms in America. In December 1864, Brigadier General James R. Chalmers, along with his staff and escort, made their headquarters at Belle Meade at the invitation of William Giles Harding, a hard-core secessionist who was once jailed by Andrew Johnson. Chalmers commanded a veteran cavalry division that was tasked with holding John Bell Hood’s left flank and disrupting traffic on the Cumberland River. The Rebels constructed rifle pits near Belle Meade.

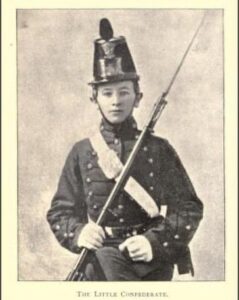

The young Captain James Dinkins was a member of Chalmers’s staff. After the war he wrote 1861-1865 by an Old Johnnie. It is a vivid memoir and valuable account of the war. He also left posterity a rendition of the Rebel Yell, made in 1930 and held by the Library of Congress. He was also a New Orleans banker, and as benefiting his high status was buried in Metairie Cemetery, the resting place of such famed Confederates such as Hood, P.G.T. Beauregard, Richard Taylor, and most of the Washington Artillery. Furthermore, he also left accounts of a dramatic fight at Belle Meade that has entered the lore of the battle of Nashville.

On the morning of December 15, Chalmers left Belle Meade to take part in the battle, leaving wagons and baggage behind on their departure. As the fighting turned against the Confederates, Dinkins was ordered back to Belle Meade to retrieve the wagons. They found the Federals had already captured and burned the wagons. Dinkins and his men charged from behind one of Harding’s barns, and during the engagement the fighting was close enough to the mansion that rounds were “clipping the shrubbery and striking the house.”

Dinkins stated that a fellow officer named Bleecker saw Harding’s eighteen-year-old daughter Selene standing on the front porch, waiving her handkerchief. He wrote, “The bullets were falling thick and fast about her, but she had no fear in her heart. She looked like a goddess. She was the gamest little human being in all the crowd. Bleecker then passed by her, took the handkerchief, urging her to take shelter from the fray.” That one story has been told time and again ever since Belle Meade became a public museum in the mid 1950s. The storyteller even has physical proof in the marks on the face of the columns that adorn the front porch.

In the first telling, published in 1897, Dinkins said the interaction with Selene Harding happened to Bleecker. In a 1926 issue of Confederate Veteran, the interaction with Selene Harding occurred with Dinkins, not Bleecker. Service records can be easily obtained for Dinkins. As for Bleecker, there are 4 records that appear to an E. Bleecker, one being a muster roll showing him absent for sickness, the other is a pay stub, both dated 1862. He has no records in 1863, or 1864. Bleecker’s presence cannot be dismissed or confirmed.

There is the dearth of eyewitness accounts. No member of the Belle Meade family ever wrote about the incident, or made mention of any events during the battle. Selene died five years after Dinkins’s first account. The only possible corroboration came from Joe Carter, a former slave who was employed at Belle Meade following his emancipation. He recalled the gunfire on the property during the battle. He stated that he and other small children were hidden from the danger in the spring house near the front lawn of the mansion.

One piece of evidence against Dinkins is the lack of physical damage. On August 17, 1940, Lester Jones photographed Belle Meade mansion from numerous angles for the Historic American Buildings Survey. None of these images show any of the marks on the columns that are visible today. Because the columns are made of sandstone and porous, the marks are most likely caused by more than 150 years of exposure to the elements, such as freezing and thawing rain. In addition to the 1853 mansion, the other antebellum structures still remaining are the Harding Cabin, Gardener’s House, Smoke House, and Mausoleum. There is no damage to any of these buildings that time alone has not brought about.

There was fighting at Belle Meade on December 15. The reports of Brigadier Generals James Wilson and Edward Hatch mention fighting at Belle Meade and taking the wagon train. However, the grand and dramatic skirmish recalled by Dinkins, with Selene cheering on the Confederates, is less likely. Dinkins fought a hard, long war and had many valuable stories to share that made him a celebrated figure in the postbellum south. Yet, at least one of those stories about Belle Meade is likely exaggerated.

Dinkins was possibly motivated by Belle Meade’s ties to the Confederacy during and after the war. Belle Meade was Chalmers’s headquarters before the battle, and Dinkins was there, and both men visited the home after the war, notably for Benjamin Franklin Cheatham’s wedding. Brigadier General William H. Jackson, who also commanded a cavalry division in Hood’s Tennessee campaign, married Selene and gained recognition for breeding horses and his support of the Grange movement. Stephen D. Lee and Fitzhugh Lee were prominent visitors. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s escort had a reunion in the carriage house in 1896. Dinkins might have wished to enter Belle Meade and Selene Harding into the Lost Cause narrative that Dinkins sustained until his death in 1939, just weeks before Germany invaded Poland.

This is great! Debunk ALL the Lost Cause magnolias..

This article, which I helped write, does not debunk a Lost Cause myth but asks to question a possible embellishment that is part of the lore of a little researched battle.

Fascinating story and excellent investigative research. Seemingly, another example of Lost Cause embellishing history, if not re-writing it. Not that Union accounts didn’t also engage in burnishing if not fabricating – thus the need to fact check and corroborate, as this article does. Well done.

Humans always embellish. If you think the Civil War is tough to understand try the Mongol Empire.

Good Sun.Morn, So I just got up Opened Email Inbox & Started Reading This Article !PLEASE Write More I was Truly Enchanted,Mind Wandering,Trying to Picture in Mind of Events Being Skillfully Writen Before Me .Please,Please Wite More Here. Thank You

Nice article and excellent research. While I suppose the story still could be true, the incident may be what was said at the end of “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance”: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

Fewer words said in a film are more central to understanding history and how it is written.

Always question the myths. Always seek out the evidence excellent work!

I live across the road from Belle Meade. Great article.

You should read James Dinkens book “1861 To 1865”. In that book Dinkens used his own notes from his time in the war first as a private in The Army of Northern Virginia where he refers to himself as “the little confederate” and later as a lieutenant under General Chalmers in the Mississippi calvery where he use the alias Blecker when referring to himself. Blecker and Dinkens are the same person. Read the book!