The Marine Devil: A Proven Foreign Submarine Offered to the U.S. Navy

“SIR: I much regret to inform the Department that the U.S.S. Housatonic, on the blockade off Charleston, S.C., was torpedoed by a rebel ‘David’ and sunk on the night of the 17th February about 9 o’clock.”[1] Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren and a handful of others hold the dubious distinction of reporting an event that changed warfare forever. The Confederate-built submersible H.L. Hunley successfully destroyed a Union vessel, demonstrating the practicality of subsurface operations. Unseen craft shielded by the water above them could explode a ship without detection, exploiting a new dimension of naval combat. This was far from the first submarine used in military affairs, and like its predecessors possessed limited maneuverability and survivability, only operable in ideal circumstances.

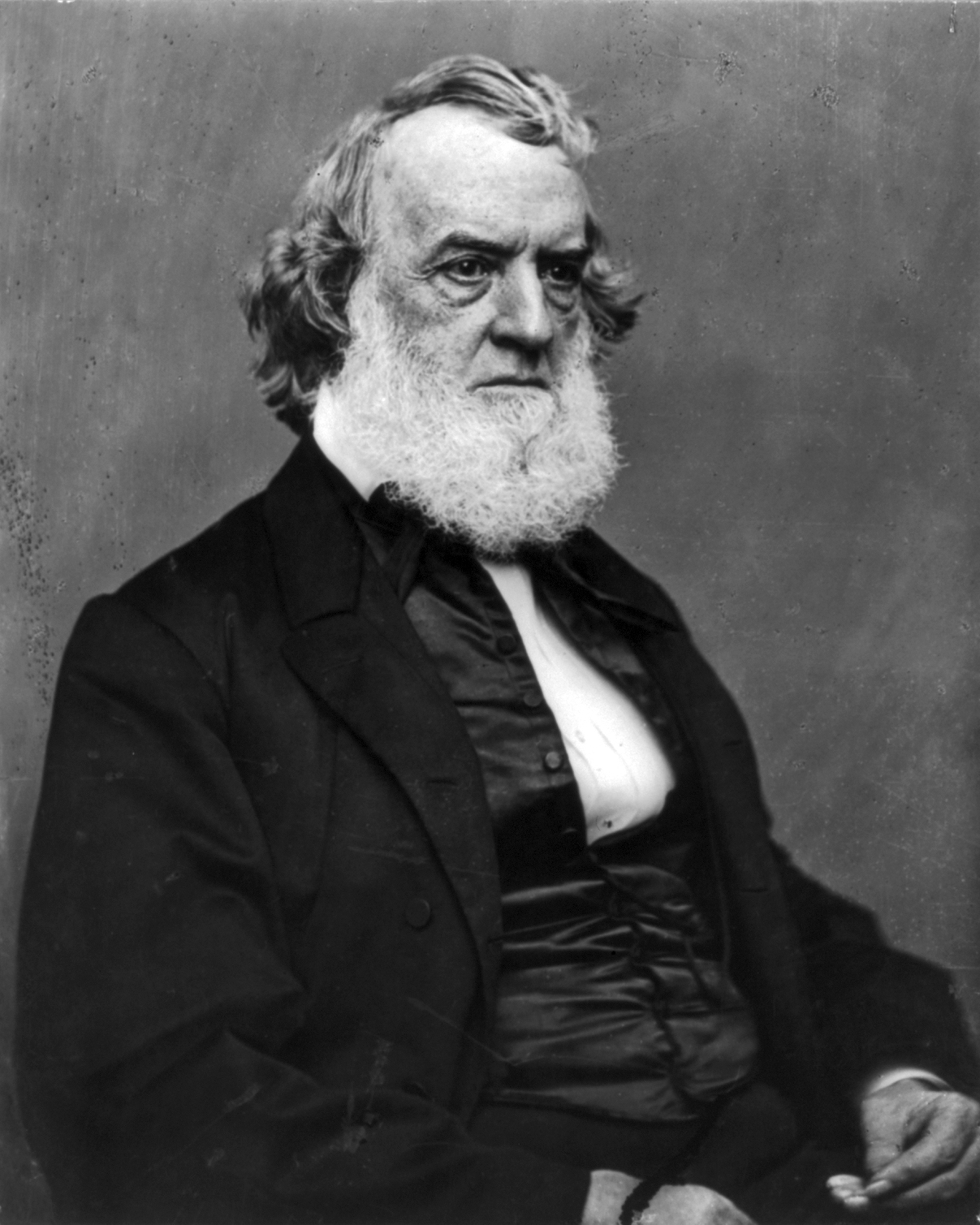

Nearly all the attention on Civil War submarines goes to the Hunley or the U.S. Navy’s Alligator. These two constitute only a fraction of over twenty submarines developed and deployed over the course of the conflict. They greatly varied in effectiveness, and even the most advanced were more dangerous for their crew than for any enemy ship.[2] Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles had an opportunity to acquire a submersible that underwent extensive trials by foreign nations, but ultimately the offer fell through.

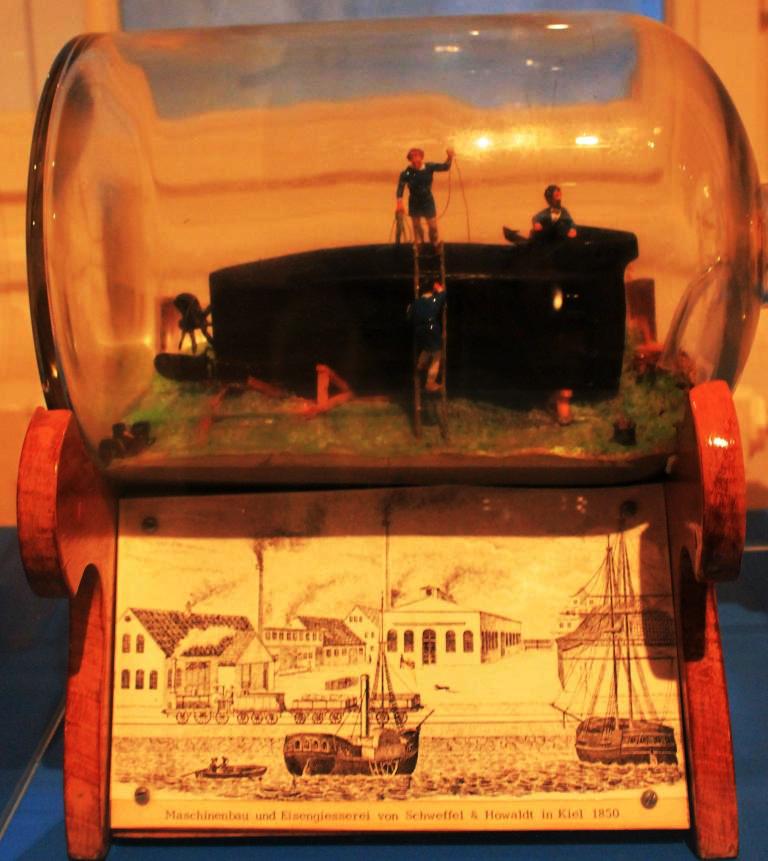

Wilhelm Bauer was an officer of artillery under the Duke of Holstein in the German/Danish war for Schleswig-Holstein from 1848-1851. In January 1850, Bauer drafted a proposal for an underwater vessel to break the Danish blockade by attaching explosives to a ship’s hull. Bauer first gained approval for a miniature clockwork model and then a full-scale submersible. With insufficient funds, Bauer had to cut back on components, reducing operational depth to only thirty feet, as opposed to the planned 100. The submarine, christened Der Brandtaucher (Diving Incendiary), was towed into the water on December 18, 1850.[3]

At a formidable 26 feet long, 6.5 feet wide, and with a displacement of 30 tons, the Brandtaucher was extremely ambitious. It contained a crew of three, who ran on a hamster wheel-like mechanism to turn its propeller. In the space between the crew compartment and keel, water could be admitted or expelled by hand pumps to lower and raise the craft. Despite its intricate engineering, it was soon dead in the water, sinking to the bottom before being raised and readied for her first manned trial.[4]

Bauer sought to prove that the sub could venture beyond the stated maximum depth. It did just that on February 1, 1851, sinking to a depth of fifty feet. Its inventor was accompanied by a blacksmith and a carpenter, neither of whom had any practice with the submarine. A parade of onlookers could immediately tell the vessel was freely sinking, and attempts to tow it to the surface were ineffective. The ingenious Bauer knew that the hatch could be opened when the pressure on the interior equalized with the outside (thanks to water seeping in). [5] Despite his crew panicking, they surfaced after over seven hours in the middle of their own funerals.

The end of the war in 1851 terminated the military imperative for Bauer’s craft. He took his designs first to Ludwig I and Maximillian II of Bavaria and Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary. In 1853 he met with the British Royal Family. The concept intrigued Prince Albert, who provided Bauer with monetary backing and powerful support.[6] The Royal Navy begrudgingly took on the project, seeing the slow and low-mobility craft as unfitting with their highly mobile doctrine. Soon after construction started, Bauer felt his ideas were being stolen and thought the contract awarded him was unfair. The inventor turned to the United States government, which rejected his proposal.[7] With the Crimean War brewing, the inventor took his talents to Russia. [8]

Russia, already well-versed in using naval mines, saw promise in the design and had a pressing need for novel projects to defend against the coalition’s navies.[9] In 1855, sponsored by the Grand Duke Constantine, Bauer built the 52-foot sub The Marine Devil.[10] One hundred and thirty-four tests were completed in St. Petersburg and Kronstadt from 1856-1858.[11] He also conducted an experiment on underwater sound during the coronation of Alexander II. A band on the Marine Devil played the National Anthem, which was audible to other ships nearby through their hulls.[12] The end of the war and conservative Russian naval officers brought an end to Bauer’s position, and he left Russia in 1858.[13]

The submersible pioneer declared ironclads would have little success as artillery advanced, promoting the need for his inventions.[14] Others campaigned for Bauer as well, such as E. Beidermann, an American in London who wrote in to Gideon Welles about The Marine Devil in 1862. Welles endorsed the idea, noting the propeller functioned like that being used on the Brutus De Villeroi design the Navy was already sponsoring. He wrote, “This propeller for submarine work is similar to one now under contract by the Navy Department (the USS Alligator). This novel mode of warfare we consider legitimate since the enemy has inaugurated it against us.”[15] Nevertheless, budget restrictions left little room for novel experiments, and the plan never developed. Bauer could not secure a buyer for his craft, and he died in 1875.[16]

Would adoption of The Marine Devil have any bearing on the war? It faced the same lack of speed, navigability in open water, and oxygen levels that its contemporaries did. The only significant advantage it possessed over other craft was its proven record of not being fatal to its crew. No doubt an important feature, but its combat capabilities remained unproven.

[1] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Vol. XV: 329.

[2] Mark Ragan, Submarine Warfare in the Civil War (Cambridge, Ma: De Capo Press, 2003): ix.

[3] Richard Compton-Hall, Submarine Boats: The Beginnings of Underwater Warfare (New York: Arco Publishing Company, 1983): 103-109. http://militaryhonors.sid-hill.us/history/gwmjh_archive/Documents/Compton-Hall_060.html.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Michael Wynford Dash, “British Submarine Policy 1853-1918,” PhD. Diss., (King’s College, University of London, 1990): 37. (https://www.strangehistory.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Pages-from-doctorate.pdf

[7] Richard Compton-Hall, Submarine Boats: The Beginnings of Underwater Warfare 103-109.

[8] Michael Wynford Dash, “British Submarine Policy 1853-1918,” 38.

[9] Andrew Lambert, The Crimean War: British Grand Strategy Against Russia, 1853-56 (London: Routledge, 2016): 20. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781315615110/crimean-war-andrew-lambert.

[10] Richard Compton-Hall, Submarine Boats: The Beginnings of Underwater Warfare, 103-109.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] James P. Delgado, Silent Killers: Submarines and Underwater Warfare (Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2011): 38.

[14] Richard Compton-Hall, Submarine Boats: The Beginnings of Underwater Warfare, 103-109.

[15] Mark Ragan, Submarine Warfare in the Civil War, 39-40

[16] James P. Delgado, Silent Killers: Submarines and Underwater Warfare, 38.

Contrary to popular belief, there were a lot of submarines operating during the Civil War, including the James River and off major blockaded ports, including Charleston and Mobile. Some of them were quite advanced. Most of these records were destroyed at the end of the war, and those that remain, scattered. Mark Ragan broke this story open with his pair of books, both of which are highly recommended.

Fascinating article. Amazing that the crew themselves were at such high risk of death.

Gotta marvel at the sheer guts of those crewed such vessels back then. Wow.

i am not sure Bauer’s machine was any safer than Hunley … your account of having to equalize the pressure between the sea and crew compartment meant that the boat was either flooding or stuck on the bottom … in the latter case, Bauer would have deliberately flooded the crew compartment to equalize the differential pressure, get the hatch open, escape the boat, and swim to the surface … this is how escape trunks on modern submarines work … Bauer was definitely a cool customer … GREAT POST, THKS.

His first machine most certainly was not! And that submarine was stuck on the bottom. However, the subsequent Marine Devil underwent 134 tests without any significant mishaps. Thanks for reading!