“Our Majority in the Senate Depends Upon the Release of Major White”

In the classic 1963 movie, The Great Escape, a group of lounging Allied POWs perk up at the sight of a newly arriving British officer. They are quickly warned not to take special notice of the important newcomer because “the goons [Germans] may not know who he is.”[i] A century before the movie, another POW hoped that the “goons” (Confederates) did not know who he was. If they found out, the result might be not only misery for the POW, but a political monkey wrench thrown into a key Northern state’s support for the war effort.

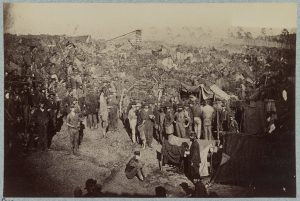

Major Henry Lloyd White, of the 67th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, was captured in the June 1863 debacle (for the Union) that was the Second Battle of Winchester.[ii] White was not simply one more U.S. officer on his way to Richmond’s Libby Prison; he was a sitting Pennsylvania state senator. Worse, at the time the Republican Party held a mere one-vote margin in that state’s senate, scheduled to commence a new session in January 1864. With White’s capture, Pennsylvania Republicans lost their majority and with it, control of the upper legislative chamber. Moreover, the state constitution provided that whomever the senate chose as its speaker became governor if the incumbent died or was incapacitated. With Governor Andrew Curtin, a key Lincoln Administration supporter, then in ill health control of the senate became of paramount importance to the Union war effort.[iii] This made Major/Senator White the most important POW held by the Confederates. Did the “goons” (Confederates) know it?

Simon Cameron certainly did. On October 15, the ex-Secretary of War and Pennsylvania political powerbroker wired Abraham Lincoln: “Our majority in the senate depends upon the release of Major White. He was captured with Milroy’s command and an especial exchange ought to be made for him.”[iv] The race was on to get White back to Harrisburg in time for the January 1864 senate session.

Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton wasted no time. The same day as Cameron’s telegram, Stanton wired Solomon Meredith, the U.S. Agent for Exchange of Prisoners, ordering him to make an immediate exchange for White. Clearly not wanting to tip off the Confederates to White’s true value, Stanton cloaked his urgency with a ruse. Stanton wrote that White had been part of Milroy’s command, and White’s testimony was needed for a court proceeding (probably referring to the Court of Inquiry examining Milroy’s conduct in the loss at Winchester).[v]

Unfortunately for Stanton, the Republicans, and especially White, the Confederates already knew who White was, and his unique political value. Meredith’s counterpart, Confederate Exchange Agent Robert Ould, had been tipped off. Ould later acknowledged that “extraordinary efforts [were] made to secure for him a special exchange.” But Ould refused to give up White, precisely because “He had been elected as a Republican to the Pennsylvania Senate, which, without him, was equally divided between the war and anti-war parties. His presence was needed to effect an organization and working majority in that body. I had learned these facts from more than one quarter, and was not disposed to assist in giving aid and comfort to the war party.”[vi]

Thus it was a deadlocked Pennsylvania senate that convened on January 5, 1864. Chaos and acrimony resulted. Bucking tradition, the Republican speaker for the prior senate session refused to resign, insisting that he remained speaker until his successor was elected. The Democrats protested. They deemed the new session illegitimate until a new speaker was chosen, which the deadlock precluded. To enforce their position, senate Democrats announced that they would refuse to allow the passage of any legislation, lest they be seen as accepting the holdover speaker’s legitimacy.[vii]

Republicans and their newspaper allies raged that the Democrats were dishonorably taking advantage of a loyal soldier’s misfortune. They derided their political opponents as “Copperheads” who were conspiring with Jefferson Davis to weaken the war effort. Democratic papers retorted “better no legislation at all than such as Abolitionists will inflict upon our State,” coyly suggesting that if the Republicans truly wanted a speaker to start legislative business, all they had to do was elect a Democrat. This, one journal observed, would also promptly secure White’s release (implicitly conceding that the Confederates were refusing his exchange in support of the senate Democrats). The Democrats did offer a deal under which they would support a Republican speaker in return for certain legislative posts; this compromise was rejected.[viii]

The Republicans sought to break the impasse by embarrassing their adversaries. They offered “resolutions of thanks to Generals George Meade and Ulysses Grant, [and] bills to increase the pay of soldiers.” The Democrats voted no each time. The Republicans upped the ante. They offered bills “approving of the Bible, the institution of marriage, and the divinity of God.” The Democrats stubbornly blocked each measure, intent on upholding their position that the senate had not yet been legally organized.[ix]

The impasse caused by White’s imprisonment had consequences beyond such gamesmanship. Interest on Commonwealth bonds was coming due on February 1.[x] If the legislature passed appropriate legislation, the interest could be paid in inflation-eroded greenbacks. Pennsylvania would save $500,000, money that could be used for the war effort. The Democrats blocked the measure.[xi]

Meanwhile, what of Major White and the attempt to win his release? As noted, back on October 15, 1863 U.S. Exchange Agent Meredith had been directed to secure White’s immediate exchange. The Official Records do not reveal what Meredith said to Ould, his Confederate counterpart, but presumably Meredith offered a Confederate major in exchange for Major White. Whatever the offer Ould, knowing White’s political value, refused.[xii]

Ould’s assessment of White’s value was confirmed by the North’s next move. Remarkably, in exchange for a mere major, on January 13, 1864 the U.S. offered to free a Confederate Major General, Issac Trimble. Again, Ould refused.[xiii] White was not going anywhere, especially not back into the Pennsylvania senate chamber.

White himself had other ideas. He determined to escape. Indeed, the first of his five escape attempts brought him face to face with his nemesis, Ould. In November 1863, learning of an agreement to resume the exchange of medical officers, White impersonated a Union doctor and boarded the exchange ship travelling to City Point. Ould was alerted to White’s subterfuge. Ould wrote that ‘I immediately directed the prisoners to be drawn up in line on the shore… I then raised my voice and shouted: “Colonel [sic] Harry White, come forth.” He stepped in front at once … It was a heavy blow to him, struck at the moment when he was sanguine of his liberty. Two minutes more would have placed him on the “New York,” where he would have been safe, even if his disguise had been there detected.’[xiv]

White was returned to Libby Prison and “confined in a dungeon until Christmas.”[xv] On Christmas day, he was transferred to the POW camp in Salisbury, North Carolina. General John Winder, in command of CSA prisons, stressed the need to keep close watch on White: “I send you Major White of the 67th Pennsylvania. An important prisoner. You will deprive him of all money and valuables and place him in close, separate and solitary confinement.” White was kept in harsh confinement until mid-March 1864. The Confederate goal was to prevent White from smuggling out a letter of resignation from the state senate.[xvi]

The rebels were too late. After Ould had personally foiled his escape attempt, White gave the doctor whom he had impersonated a resignation letter hidden in a Bible. The doctor was duly released, and in December 1863 provided White’s father with the precious document.[xvii] The father, still hoping that his son would be restored both to his bosom and the senate, kept the resignation secret until the last week of January 1864.[xviii]

A special election then resulted in a Republican replacement for White, who took his seat on February 29. Finally, the deadlock was broken.[xix]

White had saved his political comrades. He next turned to saving himself. On May 29 White jumped off a moving train that was taking him to Andersonville. He was recaptured after two days.[xx] In June he tried again but failed. In July he once again escaped a train carrying him to Andersonville, cutting his way out of the car at night. This time White, aided by enslaved persons, evaded capture for 29 days. The Confederates used bloodhounds to track him. White’s encounter with the beasts left him with life-long scars on his arm.[xxi]

White’s fifth escape attempt was less dramatic but effective. In September White, now imprisoned in Charleston, South Carolina, simply joined a group leaving for a POW exchange with Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s forces. By this bold but simple ploy White finally secured his freedom.[xxii]

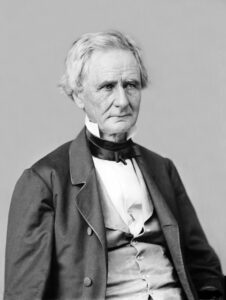

After briefly serving on the staff of Maj. Gen. George Thomas, White was sent home, arriving on October 5. Cameron, who had first raised White’s special case, employed him as an aide while White recuperated from his travails.[xxiii] Governor Andrew Curtin commissioned White colonel of his regiment. Lincoln awarded him a brevet to Brigadier General. White’s old constituents sent him back to the state senate in the Fall of 1865.[xxiv] White was back in the seat that had caused him so much trouble.

[i] The Great Escape, https://archive.org/details/the-great-escape-1963-full-hd-1080p, at 25:05-26:20. The newcomer is “Big X,” the head of POW escape operations.

[ii] Almost 4,000 Union prisoners were taken from General Robert H. Milroy’s command in the June 13-15 battle. Edwin B. Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, pp. 86-89 (Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, NY 1984).

[iii] Arnold Shankman, “John P. Penney, Harry White, and the 1864 Pennsylvania Senate Deadlock,” The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, Volume 55, Number 1, pp. 77-86, at p. 77 (January 1972), https://journals.psu.edu/wph/article/view/3150/2981.

[iv] The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of The Official Records of The Union and Confederate Armies, Series II, Vol. 6, 380 (U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1880 – 1901) (hereafter OR). Unless noted, all ORreferences hereafter are to Series II, Volume 6; Stewart Sifakis, Who Was Who In The Civil War, p. 102 (Facts on File Publications, New York, NY, 1988).

[v] OR, 141, 381; Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War: General Milroy is Spared a Court Martial, October 27, 1863, https://abrahamlincolnandthecivilwar.wordpress.com/2013/10/27/general-milroy-is-spared-a-court-martial/.

[vi] Judge Robert Ould, “The Exchange of Prisoners,” The Annals of the Civil War: Written by Leading Participants North and South, Alexander Kelly McClure, Ed., p. 56 (The Times Publishing Company, Philadelphia, PA, 1879), https://www.pedseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2001.05.0012%3Achapter%3D3%3Apage%3D32.

[vii] Shankman, pp. 78-79.

[viii] Shankman, pp. 79, 81-82.

[ix] Shankman, p. 80.

[x] In June 1861 Philadelphia financier Jay Cooke had successfully marketed $3,000,000 in Pennsylvania bonds to raise money for the war effort. Roger Lowenstein, Ways and Means: Lincoln and His Cabinet and the Financing of the Civil War, p. 49 (Penguin Books, New York, NY, 2022). It was probably interest on these bonds that was coming due.

[xi] Shankman, p. 81.

[xii] It may be coincidental but in two separate letters, each dated October 27, Ould tells Meredith that he (Ould) will not exchange a prisoner in captivity for one on parole, as Meredith had requested (in an October 18 letter not found in the OR). Ould had just declared a paroled Confederate colonel exchanged. Considering the date of events, it may be that Meredith had asked that White be exchanged for the colonel. OR, 430.

[xiii] OR, 839, 871. In correspondence to Ould, Trimble was mistakenly referred to as a Brigadier General; in fact, he had been promoted to Major General in April 1863. Mark M. Boatner, Civil War Dictionary, p. 849 (David McKay Company, Inc., New York, NY, 1988).

[xiv] Ould, p. 56. The exchange took place on November 24, 1863. OR, 559, 565-566, 566.

[xv] William W. Hassler, “Harry White, General, Senator, Judge and Master of Croylands,” p. 2, The Historical and Genealogical Society of Indiana County, PA (Fall, 1967), https://digitalarchives.powerlibrary.org/papd/islandora/object/papd%3Aaiupa-cw_138.

[xvi] Joshua Thompson Stewart, “General Harry White,” Indiana County, Pennsylvania: Her People, Past and Present, Embracing a History of the County, Vol. 1, pp. 582-583 (J. H. Beers & Co., Chicago, IL, 1913), https://digital.libraries.psu.edu/digital/collection/digitalbks2/id/34562/rec/1.

[xvii] Stewart, p. 583; Shankman, p.83.

[xviii] Shankman, p. 83.

[xix] Shankman, pp. 84-85.

[xx] Stewart, p. 583. White kept a diary recounting his escape and brief freedom. War Prison Diary of Harry White (Transcription), Indiana University of Pennsylvania, https://digitalarchives.powerlibrary.org/papd/islandora/object/papd%3Aaiupa-cw_3?search=harry%2520white; see also “Letter from B. B. Sprague to Thomas White, July 24, 1864,” White Collection, The Historical and Genealogical Society of Indiana County, PA, https://digitalarchives.powerlibrary.org/papd/islandora/object/papd%3Aaiupa-cw_96?search=harry%2520white.

[xxi] Hassler, p. 2; Stewart, p. 583.

[xxii] Frank Pollicino, “The Exploration of A Legend,” The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, Vol. 53, Number 3, pp. 243, 246 (July, 1970), https://journals.psu.edu/wph/article/view/3068/2899; Hassler, p. 2; Stewart, p. 583.

[xxiii] “Letter from Simon Cameron to Thomas White, October 27, 1864,” White Collection, The Historical and Genealogical Society of Indiana County, PA, https://digitalarchives.powerlibrary.org/papd/islandora/object/papd%3Aaiupa-cw_98?search=harry%2520white.

[xxiv] Stewart, p. 584. Perhaps not surprisingly, White was instrumental in sparking the convention that amended the Pennsylvania state Constitution, effective January 1, 1874, to create the office of Lieutenant Governor, whose incumbent was charged with breaking ties in the state senate. Stewart, pp. 584-585; 1874 Constitution of Pennsylvania, Article IV, Section 4, https://archive.org/details/constitutionofp00penn/page/n19/mode/2up.

Kevin, I found this to be quite interesting. We have all heard of politicians donning the uniform. Here is one politician whose wartime activity had a real and immediate impact on political activity on the home front. Very cool stuff.

Thank you Neil. Yes it’s an interesting story. But it really confused me when I first happened to run across Cameron’s telegram and then saw Stanton’s explanation for why he supposedly needed White back so quickly. It made no sense and prompted me to look into what really was going on.

Great story! My great-great-grandfather, George Washington Mohney (correct spelling: Mani) was a Sergeant of Company F in the 67th Pennsylvania. He was captured at Second Winchester but was fortunate enough to be exchanged that August of 1863. Fought through the war and came home without a scratch. I have his US belt buckle, Grand Army of the Republic badges – in mint condition – and a photograph of him just after the war that looks like me dressed up in his clothes – with, of course, his Colt’s Army revolver stuck in his jacket pocket. He took it everywhere with him the last 54 years of his life…

That is a great connection. And great to have those relics.

Your ancestor was lucky to be one of those exchanged.

Thank you, Kevin – indeed. He had unnatural good luck, serving through the war from December 1861-July 1865 without a scratch, though he did suffer frostbite to his feet on the Mud March. His best friend was not so lucky – shot through the head right beside him at Cedar Creek – and his two younger brothers and their uncle perished together at Andersonville. My grandfather grew up with him living in the house, so I had the great fortune of spending 25 years living in the presence of a man who lived with Civil War soldiers, something I cherish. My Papa said that his grandfather never spoke about the war unless he asked him directly – or when his brothers and friends came over on Saturday nights and the whiskey came out and they’d sit around discussing their experiences for hours. The kids would sit in the kitchen listening to every word – and when I was a boy he told me all their stories.

Thanks for sharing this compelling narrative and making the connection to the movie “The Great Escape”! It was a joy to read and ponder your work.

Thank you kindly. Glad you enjoyed it including the movie reference.

Another analogy to The Great Escape is the fact that White ultimately escaped just by joining a group walking out of the camp. You may recall that in the movie a number of the Allied POWs tried the same tactic, joining a group of Russian laborers. It did not work out for them.

That brings to mind another great escape story, that of our rangers helping our prisoners in the Japanese prison camp at Cabanatuan, Philippines, escape in January 1945. The best of all these stories from across the wars should be collected in a book.

Fascinating, very different kind of story. Kevin, very well written.

Thank you kindly. It was a fascinating story to explore.

WOW! What a terrific tale … and your opening was clever way to hook the reader — who doesn’t love the Great Escape … Major White was definitely the “Big X” of the Civil War … senators were definitely made of sterner stuff back then … you sir are quite the story teller.

Mark, thank you. And yes, with his multiple escape attempts, Major White certainly would have been considered by the movie’s Kommandant von Luger one of the “rotten apples” to be put in the same “basket” with the other escape artists.

Did White have his baseball and glove in the cooler?

Ha!

But alas, no. Abner Doubleday had borrowed both.

Ha! And you know, I bet he went on to claim he invented them both…

if the Rebs had a Colditz they would no doubt have sent our hero there!