Slaver to Blockader: USS Nightingale in 1861

In 1861, the United States was desperate for warships. The navy was small, with half its ships deployed overseas and most remaining in the United States in a state of maintenance or layup. The Navy Department spent the war’s first months purchasing, outfitting, and deploying any ship it could get its hands on with a deck strong enough to support the weight of a cannon. They were all then sent to support the few purpose-built warships trying to implement Abraham Lincoln’s blockade. Some of these improvised warships were modern steamers, others archaic sailing vessels. Perhaps the most distinct of these makeshift blockaders was a former slaver called Nightingale.

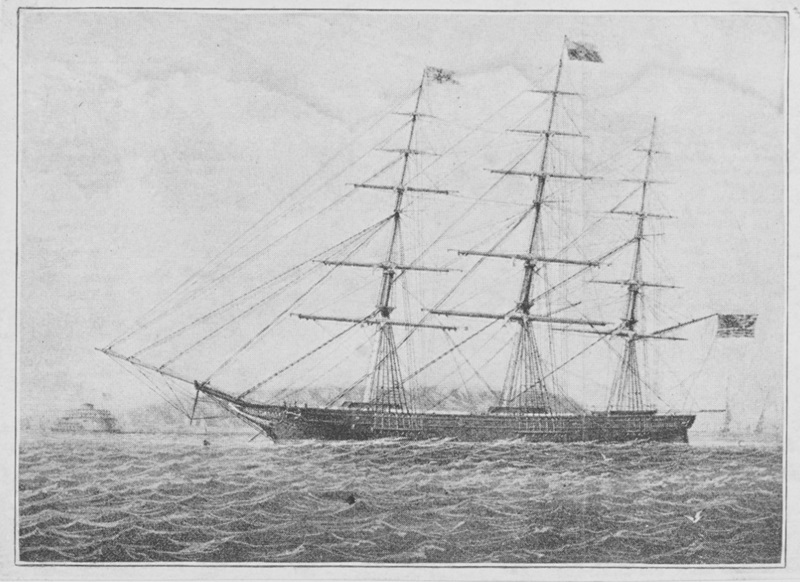

Built in Maine and outfitted in New Hampshire in 1851, Nightingale originally sailed the globe as a tea clipper. With a length of 178 feet and an overall displacement of 1,066 tons, it made runs between Shanghai and London, even losing a race on that route to the British clipper Challenger before later winning a rematch along the same route. One man sailing on the vessel called it an “extreme clipper” because of its strong construction and proven sailing speed.[1] Starting in 1853, Nightingale also spent time transporting people from England to Australia, carrying cargo from China on return trips.

The ship was in England in 1860, and its backers determined to transform it into a slaver. Outfitted for a passage supposedly to São Tomé, guns and gunpowder were loaded onboard. With preparations complete, it went down the Atlantic to Africa, even supposedly touching at São Tomé to keep up impressions. However, its goal was instead to carry enslaved people back to the Americas, likely Cuba.[2] Of course, by this point, the Transatlantic Slave Trade was outlawed by the United States and almost all nations on Earth. That did not deter Nightingale’s master, Francis Bowen, who one sailor called “the prince of slavers.”[3]

The clipper-ship being in African waters was an immediate red flag for naval forces patrolling the area. HMS Archer and USS Mystic both boarded and searched Nightingale before letting it go, each having uncovered no proof it was a slaver.[4]

What did stop the clipper was USS Saratoga, a 22-gun sailing-sloop-of-war, which was part of the U.S. squadron patrolling African waters following the Webster-Ashburton Treaty. Suspecting it of illegally carrying enslaved persons as cargo, Saratoga encountered Nightingale first on April 19, 1861, but likewise let it go after a boatload of sailors boarded and inspected the clipper. Two days later, April 21, Saratoga’s boats sent sailors who again boarded, captured, and condemned Nightingale. The capture occurred in the early hours, amidst clouds and rainstorms after the clipper’s crew had loaded enslaved persons into its hold for transport west.[5] Ironically, the officer who captured Nightingale was Lt. John Guthrie, who would be in the Confederate Navy by the end of 1861.

On Nightingale, Guthrie found “about 970 slaves” packed below deck.[6] At least 432 were children.[7] Francis Bowen and his crew were immediately confined on their own ship, and a prize crew of Saratoga’s sailors placed on the captured clipper. Bowen and one Portuguese crewman, however, escaped off Nightingale in the night on April 23.[8]

Guthrie brought Nightingale to Monrovia, where the captured enslaved African people were landed ashore. However, starvation and illness took their toll, and an estimated 150 enslaved Africans died on their way to Liberia’s capital, and freedom.[9] From there, Saratoga’s prize crew brought Nightingale across the Atlantic to New York City. The same illness plaguing everyone dropped off in Liberia also affected the prize crew, with only seven of Saratoga’s 34 sailors onboard healthy when it reached New York. Three had died on the trip.[10]

Officially condemned as a prize, the government immediately purchased Nightingale for $13,000 and impressed it into service.[11] By August, it was hastily outfitted as a storeship to support the blockade. Acting Master David B. Horne was assigned as Nightingale’s commanding officer. Under Horne’s command were fifty inexperienced sailors, almost all of whom had only just enlisted.[12]

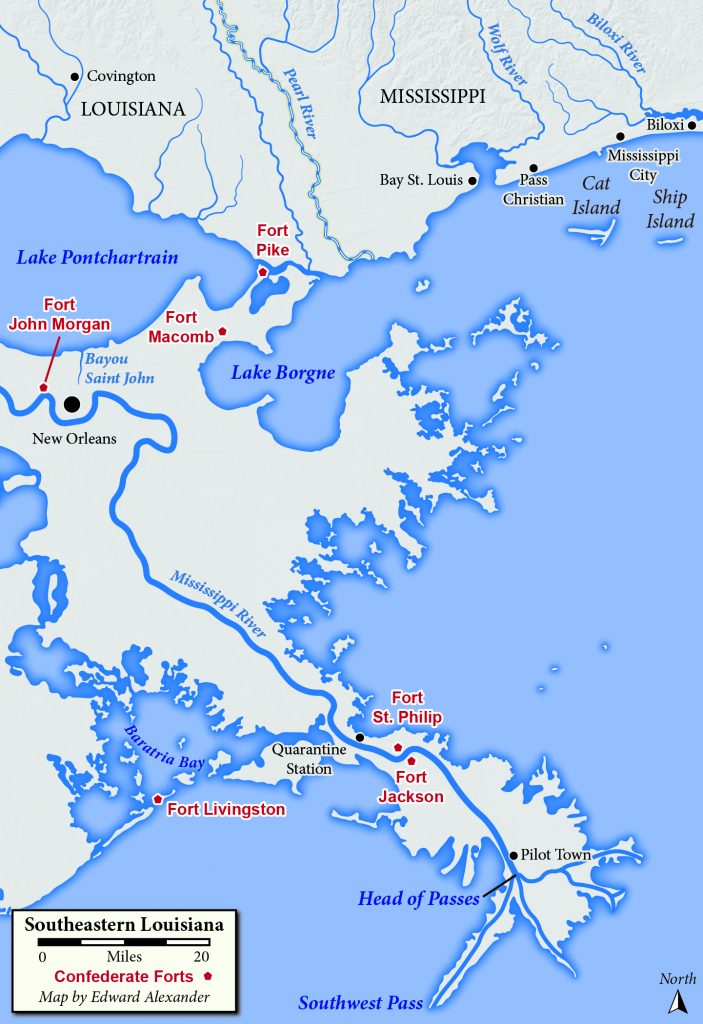

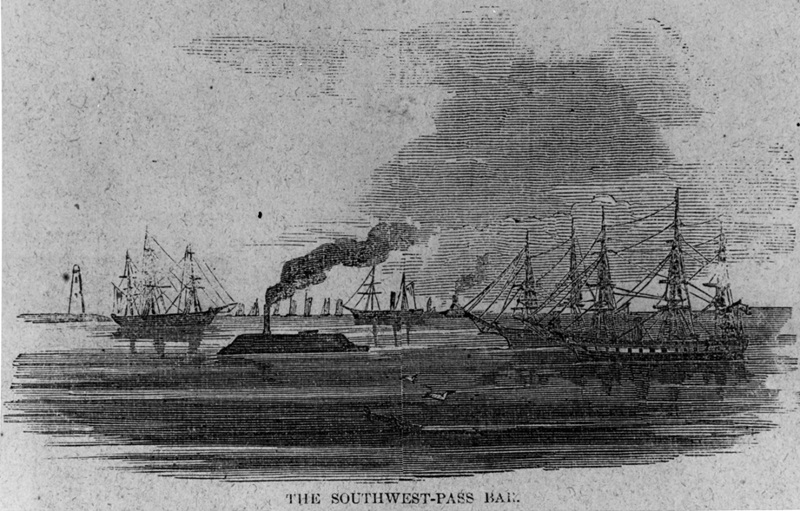

Nightingale left New York in August 1861, with orders to sail to the Gulf of Mexico. It was there by early October 1861, part of the Gulf Blockading Squadron’s cordon around the Mississippi River. Barely armed, the slaver-turned-storeship provided a staging base, fuel, supplies, and repair parts for other blockaders. It also ran aground soon after arriving, lodging itself in shoal water just outside of the Mississippi’s Southwest Pass.

While aground, Nightingale took on personnel and cargo captured nearby, including 9,000 muskets captured on the blockade-runners Ezilda and Joseph H. Toone. Besides being a supply ship, Nightingale was now a floating arsenal.

Map by Edward Alexander.

Though Horne and his small crew did not yet know it, that October 1861 would be their most trying time in the entire war. The ship remained stuck aground amidst the October 12 battle of the Head of Passes. That morning, Capt. John Pope’s flotilla of four warships was surprised by an improvised Confederate naval squadron, including the confiscated privateer-ironclad Manassas. Pope’s ships retreated from the Head of Passes, where the several passes of the Mississippi River converge into a single channel. They moved down Southwest Pass, where USS Richmond and USS Vincennes ran aground near the channel, and near Nightingale.

Horne’s ship was only one of three supply steamers outside Southwest Pass. Amidst the battle, the senior officer of those three, Lt. Edward Selden on the ship John N. Genin, received an order from Pope “to ships outside the bar to get underway.”[13] Still aground, Nightingale was trapped, and if the Confederates crossed into the Gulf of Mexico, the clipper and its captured cargo of muskets and blockade-runner prisoners would fall into Rebel hands. To prevent this, Lt. Selden ordered Nightingale abandoned and burned!

Preparations were “immediately carried out” on Nightingale, with most of the crew departing.[14] Acting Master Horne however, refused to put his ship to the torch, and the Confederate ships withdrew before they reached his vessel. Work tossing six tons of coal overboard to lighten the ship failed, and in the days after the battle in a panic about repeated Confederate attacks, Lt. Selden continuously ordered the ship torched, each time with Capt. Pope countermanding the order.[15] The ship was only refloated about a week later.

Nightingale returned to New York by the end of 1861 for a refit. From 1862 through mid-1864, it supported the Eastern Gulf Blockading Squadron in both Key West and Pensacola, Florida. The ship was decommissioned in June 1864 and sold in February 1865. Nightingale later served as flagship of the mid-1860’s Western Union Telegraph Expedition into Canada and Alaska. It remained in the merchant service until foundering in 1893.

Despite a varied record as a racing clipper ship, merchant, slaver, warship, and exploration vessel, Nightingale’s most trying moments came in 1861 when it underwent the transformation from slaver to blockader, in a way symbolizing the root causes and conduct of the Civil War itself.

Endnotes:

[1] Frank J. Mather, “A Clipper Ship and Her Commander,” The Atlantic Monthly, Vol. 94, 1904, 649.

[2] Some Ships of the Clipper Ship Era: Their Builders, Owners, and Captains (Boston: Walton Advertising and Printing Company, 1913), 37.

[3] Commodore Perkins, “Address at the Unveiling of the Statue in State House Yard, Concord, NH, April 25, 1902,” William Jewett Tucker, ed. Public Mindedness: An Aspect of Citizenship Considered in Various Addresses Given While President of Dartmouth College (Concord, MA: The Rumford Press, 1910), 188.

[4] “The Civil War in the United States,” The Morning Chronicle, London, July 1, 1861.

[5] April 19-21, 1861, USS Saratoga Logbook, Logbooks of US Naval Ships, 1801-1940, Record Group 24: Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1798 – 2007. US National Archives.

[6] April 21, 1861, USS Saratoga Logbook.

[7] “Capture of a Slaver,” New York Times, June 16, 1861.

[8] April 23, 1861, USS Saratoga Logbook.

[9] “News of the Day,” New York Times, June 16, 1861.

[10] Nightingale I (Ship), Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/n/nightingale-i.html, accessed September 2, 2024.

[11] Some Ships of the Clipper Ship Era: Their Builders, Owners, and Captains (Boston: Walton Advertising and Printing Company, 1913), 37.

[12] Complete Descriptive List of Muster Roll of the Crew of the U.S. Ship ‘Nightingale’ before sailing from New York for Hampton Roads on the 18th day of August 1861, Muster Rolls of USS Nightingale 1861-1864, Muster Rolls of Naval Ships, 1/1/1860 – 6/9/1900, Records Group 24, US National Archives.

[13] French to McKean, October 22, 1861, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Vol. 16, 714.

[14] October 12, 1861, USS Nightingale Logbook.

[15] Taylor to Bailey, October 29, 1861, ORN, Series 1, Vol. 16, 719.

Neat discussion.

Excellent post!

Great discussion. It is always good to read more on the naval aspect of the war.

Wild.