David Farragut and Maritime Statecraft in Cuba, February 1862

It was a pleasant day in early 1862. Flag Officer David Farragut stood on the quarterdeck of his flagship, USS Hartford, pacing anxiously. Hartford had only recently entered the Gulf of Mexico, with Farragut mandated to enter the Mississippi River and capture New Orleans. Running along the coastline, Farragut and the rest of Hartford’s crew were manned and ready for anything. Running into Confederate ships was likely in these waters. Looking through his spyglass, Farragut could see the port city his flagship was closing. Inside were a host of ships, almost all war-steamers. As Hartford entered the harbor and came to anchor at 7:15 pm, it did so amidst a massive invasion fleet.[1]

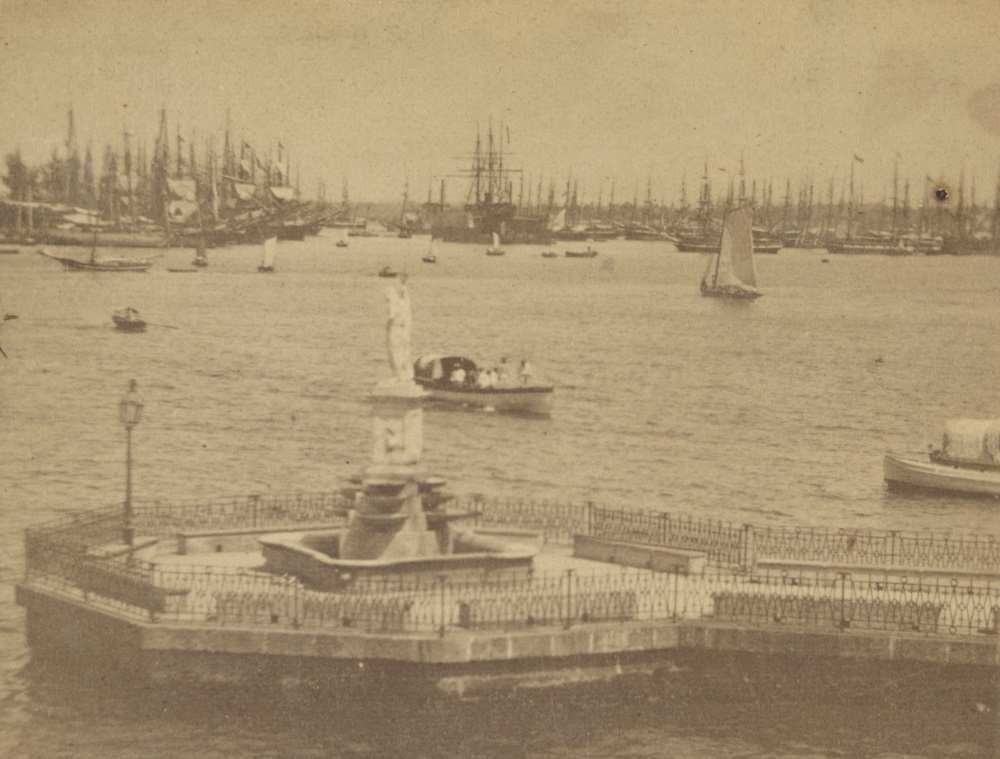

Farragut and his sailors were not approaching New Orleans however. The campaign for that city was still two months away. The ships anchored near Hartford were not U.S.-flagged vessels. Instead, February 15, 1862, found Farragut’s flagship entering the port of Havana, the center of Spanish colonial power in the Americas. Packed into the harbor were hosts of warships. Many were Spanish, of course, but many were not. There were numerous British- and French-flagged warships moving in and out of the harbor as well.

Havana was the crown jewel of the Spanish empire, with its famed Castillo de los Tres Reyes Magos del Morro guarding the harbor’s entrance. For many of Hartford’s sailors, only recently enlisted, it was their first time abroad. Landsman Bartholomew Diggins, who joined the navy on New Years Eve 1861, summarized his apprehensions. “Here I experienced for the first time the strange sensation of being in a city full of people where no one could understand me, where my tongue was of no use, and was compelled to make my wants known by signs or any other way I could.”[2]

Hartford reached Havana after having left Key West, Florida that very day. When the flagship anchored, it did so in a bay Landsman William C. Holton described as “beautiful in the extreme.”[3] There were two reasons Farragut took this detour to Cuba instead of continuing directly to formally assume charge of the Western Gulf Blockading Squadron and prepare his advance into the Mississippi. The first had to do with matters pertaining to the blockade. The second was to send an unstated diplomatic message.

Havana was the closest foreign port to the Confederate cities of New Orleans, Mobile, and Pensacola. Thus, a vital connection between these ports and Cuban waters was quickly forged in attempts to bring supplies into the fledgling Confederacy and to export cotton out. Taking New Orleans for example, port records indicate that fifteen blockade-runners reached the Crescent City from Havana between May 1861 and March 1862, and another forty-three vessels cleared New Orleans for Havana in that same time, many being “small vessels loaded with cotton.”[4]

A staff officer observed rebel flags “floating high in the air from the masts of three Confederate merchantmen” in the harbor, clearly demonstrating the link between Havana and Confederate Gulf ports.[5] Hartford’s anchoring was meant to be a clear challenge to these ships specifically and this link generally, implying Havana was closed for business with rebels. Indeed, the flagship remained anchored for forty-eight hours in the hope it might “have a good effect upon the authorities” who often sympathized with the new Confederate government.[6]

The ulterior purpose of Farragut’s visit was to send a message to the European fleets anchored within the harbor and the governments they represented. Mexico was being torn asunder after years of civil war, and the nation had defaulted on paying its debts. The European fleets were assembled as part of the military and naval forces “for the purpose of compelling the payment” by force.[7] Spanish troops had already landed in Mexico in December 1861, with British and French landings a month later. It was the first step in a decade-long French intervention that would topple Mexico’s government, replace it with Austrian Ferdinand Max, and further destabilize the nation.[8]

Farragut’s message was unwritten and unstated. Hartford’s presence was the entire communication, and the statement was clear enough to those versed in geopolitics: The United States was not abandoning its stance in the Western Hemisphere, the Monroe Doctrine was not defunct even amidst civil war, and Abraham Lincoln was not going to sanction an occupation of Mexico by Europeans.

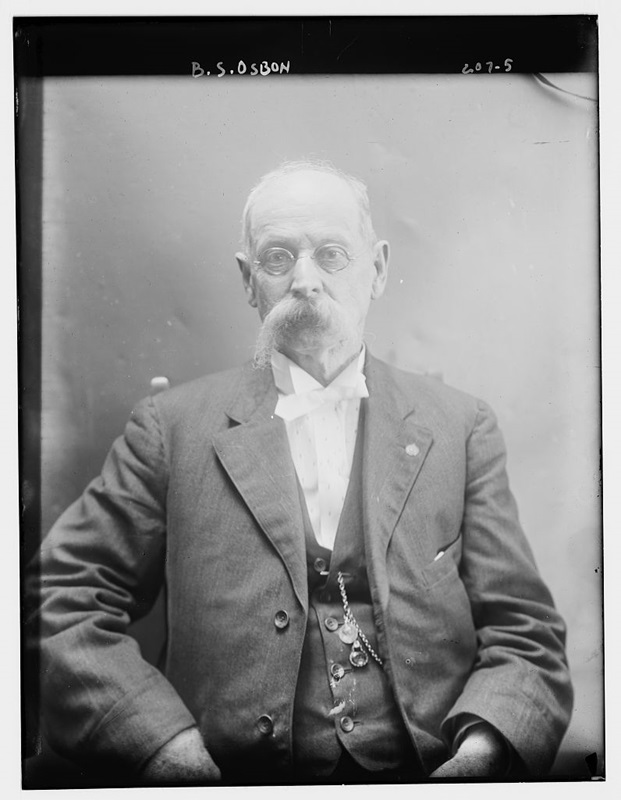

Bradley S. Osbon, a civilian volunteer on Farragut’s staff, admitted Hartford’s visit was to “show our contempt” for the European fleets and their sanction of “enemy vessels” running the blockade. Regardless, diplomatic formalities were maintained, and Hartford “burnt a good deal of powder in salutes for the Governor General, and for various commanders of the allied fleets.”[9] The flagship’s log records salutes to the Spanish flag, the Spanish admiral in the harbor, the French fleet’s admiral, and the U.S. consul.[10] The single British warship in harbor, HMS Barracouta, was not saluted, possibly as continued contempt on both sides from the recent Trent Affair.

After two days, Hartford departed Havana and set a course for Ship Island, Mississippi and ultimately New Orleans. In leaving, Farragut allegedly turned to his fleet captain in disgust. “’Well, thank God!” Farragut said. “I’m more than pleased to be out of that infernal hole. I’ve been mad clear through all day, and if it were not for the work ahead, nothing would suit me better than to go in among those fellows and give them a dose of nine-inch shells. We may have to do it yet before this war is over.”[11] The United States spent the rest of the war using diplomatic channels, naval activity, and military garrisons to keep European powers neutral and maintaining the Monroe Doctrine. Thus, Farragut’s prophesy of possibly having to use his guns against Europeans proved unrealized and Hartford’s guns instead remained focused on Confederate warships and fortifications in the Mississippi River and Gulf coast.

Endnotes:

[1] February 15, 1862, USS Hartford Logbook, Logbooks of US Naval Ships, 1801-1940, Record Group 24: Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1798 – 2007. US National Archives.

[2] George S. Burkhards, ed. Sailing with Farragut: The Civil War Recollections of Bartholomew Diggins (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2016), 6.

[3] B.S. Osbon, ed. Cruise of the U.S. Flag-Ship Hartford 1862-1863: Being a Narrative of All Her Operations Since Going Into Commission, In 1862, Until Her Return to New York in 1863. From the Private Journal of William C. Holton (New York: L.W. Paine, 1863), 15.

[4] Farragut to Welles, February 17, 1862, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Vol. 18, 30. It should be noted that the New Orleans port records only contain listings for vessels from May through August 1861, and November through March 1862. List of Vessels Arrived at New Orleans from May 15th to August 20th 1861, List of Vessels Entered and Cleared of the Port of New Orleans for the Months of January & March 1862, List of Vessels Entered and Cleared of the Port of New Orleans for the Months of November and December, 1861, and February 1862, Confederate States of America Records, Maritime 1861-1863, Box 19, Reel 12, Library of Congress.

[5] Osbon, Cruise of the U.S. Flag-Ship Hartford 1862-1863, 16.

[6] Farragut to Welles, February 17, 1862, ORN, Series 1, Vol. 18, 30.

[7] Albert Bigelow Paine, ed. A Sailor of Fortune: Personal Memoirs of Captain B.S. Osbon (New York: The McLure Company, 1907), 172.

[8] Regis A. Courtemanche, No Need of Glory: The British Navy in American Waters 1860-1864 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1977), 70-76.

[9] Paine, A Sailor of Fortune, 173.

[10] February 16, 1862, USS Hartford Logbook.

[11] Paine, A Sailor of Fortune, 173-174.

Glad to see that we were and still are referring to the “Gulf of Mexico”