Stacking Arms “What Ifs?” – Episode I: “What If” A Hungry Army Had Been Fed at Amelia Court House?

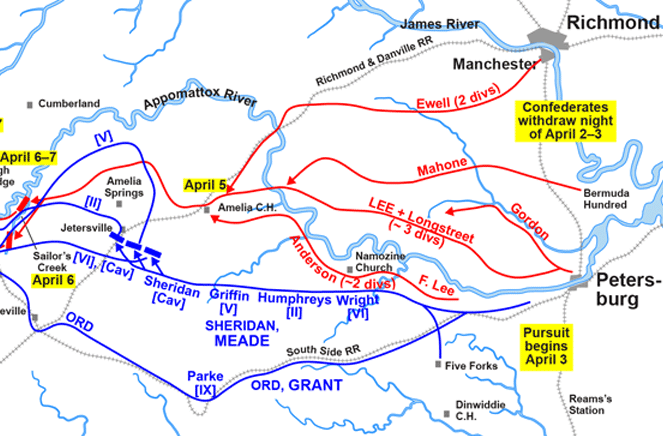

The night of April 2-3, 1865, Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia successfully evacuated the Richmond-Petersburg lines they had defended for ten months, escaping west to seek an eventual junction with Gen. Joseph Johnston’s forces in North Carolina. On the morning of April 4, Lee and the advance of his army arrived at Amelia Court House, some 33 miles northwest of Petersburg. Lee had ordered that food be ready there for his hungry troops. Lee would refresh his men, then rapidly move on, maintaining the lead that his army had gained on U.S. forces led by Ulysses S. Grant.

But despite Lee’s advance planning and orders, there was no food waiting for his men. Already weakened by months on short rations,[1] Lee knew that to steel his men for the coming trials, they needed sustenance. Lee prepared a personal appeal to area civilians to accompany foraging parties, who spent the day desperately searching for supplies. The wagons came back virtually empty. More than pained stomachs resulted. By remaining in place a day while searching for food, Lee had lost precious time in his race away from Grant’s pursuing forces.[2] As Lee explained in an April 12 report intended for Jefferson Davis, “[U]pon arriving at Amelia Court House with the advance of the army…and not finding the supplies ordered to be placed there, nearly twenty-four hours were lost in endeavoring to collect in the country subsistence for men and hours. This delay was fatal, and could not be retrieved.”[3]

Lee proceeded to explain in detail to Davis how the “fatal” delay at Amelia Court House caused by the absent supplies led to a cascading series of events ultimately dooming his army. [4] First, when on April 5 his famished troops finally resumed the delayed march, they found that Union cavalry had had time to slip in front of his planned route at Jetersville, with enemy infantry coming up in support. Lee recounted how this development blocked him from the rail line he had expected to use for future supply along the planned march route.

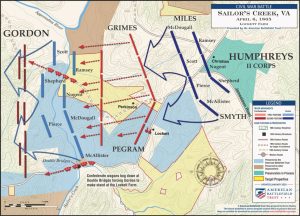

The army instead had to alter its direction and move towards Farmville, Virginia. This in turn forced his infantry to use a route that already had been assigned to the artillery and wagon trains. This “impeded our advance and embarrassed our movements.” On April 6, Union cavalry and infantry in force caught up to the army, resulting in the “Black Thursday” of the Confederacy, the battle of Sailor’s Creek. Lee lost almost 9,000 men, a quarter of his army, along with six generals captured (including Lee’s eldest son, Custis).[5]The survivors continued the march that night, but “depressed by fatigue and hunger, many threw away their arms.” Lee’s remnant, after a final breakout attempt to the west against the federal forces, surrendered at Appomattox Court House on April 9.

In true “for want of a nail” fashion, the failure to have the expected food ready for Lee’s men at Amelia Court House, in Lee’s own view, effectively drew a straight line to the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, which leads to a fascinating “what if” exercise.

We have Lee’s narrative of what happened because of the missing food, but had the supplies arrived as ordered, it is possible to conclude the following divergence from the historic timeline.

First, since Lee would not have needed to hold in place at Amelia Court House for “nearly twenty-four hours” in a futile search for food, at least some of his army, now reinvigorated by food, could have continued on its intended path, potentially reaching Jetersville before Union cavalry and especially infantry appeared in force to bar his path. As ECW’s own Rob Orrison has written, “The delay in getting his army consolidated and the delay in Amelia Courthouse trying to find provisions cost the Confederates dearly. Without these delays, it is possible that all Lee would have faced at Jetersville was cavalry.”[6] Lee would thus have not lost access to the railroad he intended as his means of further supply, and could have continued his movement to the south towards Johnston’s forces, rather than being diverted westwards towards Farmville.

Moreover, well-fed troops would not only have refreshed their strength, but also avoided the crippling loss of morale that hunger otherwise imposed on the veterans who had followed Lee thus far. Fewer would have felt the need to wander off in their own desperate search for food or simply thrown away their arms in despair.

Furthermore, the changed direction would have avoided the need to follow the same road used by the artillery and wagons, which as Lee reported to Davis greatly hampered progress. The combination of change in direction and increased speed of march, helped by the soldiers having been fed, would mean that thousands of soldiers of Lee’s army would not have been caught struggling along at Sailor’s Creek, hence, no battle leading to the loss of one-quarter of Lee’s combat force.

The result would have been significantly more men in the Confederate ranks, prepared for the next stage of the campaign and whatever that brought. Would this all have meant that Lee’s army—with Grant’s forces nipping at its heels—would have been able to effect a juncture with Johnston’s force, still more than 120 miles away in North Carolina? That outcome remains doubtful.

There would, however, have been more battles, bloodshed and death at different points along Lee’s new line of march into North Carolina. Lee’s army might have ended up being utterly torn to pieces in a series of sharp running and bloody battles, rather than at least a small core surviving long enough to surrender intact in a dignified ceremony. Indeed, Lee might have been killed along the way, perhaps forsaking calls of “Lee to the rear” while trying to lead his men in a desperate defense at some small village crossroads in North Carolina. But it seems certain that, had hardtack and salt meat been ready at Amelia Court House on April 4, the final battle of the Army of Northern Virginia would not have been fought outside of Appomattox Court House, Virginia, and Wilmer McLean’s parlor would not have earned its place in history.

[1] For months prior, Lee had been warning the Confederate Secretary of War James A. Seddon that the rations provided were too small to sustain the strength of the men, that the failure to feed them was a cause of rampant desertion, and failure to solve the problem would lead to “dire results.” Clifford Downey & Louis H. Manarin, Editors, The Wartime Papers of Robert E. Lee (DaCapo, New York, NY, 1961), Doc. Nos. 940, 945, pp. 886-887, 890 (Lee to Seddon, Jan. 27 & Feb. 8, 1865).

[2] Douglass Southall Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenants, Vol. III, pp. 689-691 (Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, NY, 1942); Douglass Southall Freeman, R.E. Lee: A Biography, Vol. IV, p. 66-68 & Appendix IV-2 (Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, NY, 1940).

[3] Downey & Manarin, Doc. No. 1005, pp. 935-936 (Lee to Davis, April 12, 1865) (emphasis supplied).

[4] Downey & Manarin, Doc. No. 1005, pp. 936-937 (Lee to Davis, April 12, 1865).

[5] “Sailor’s Creek (Sayler’s Creek),” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/sailors-creek.

[6] Rob Orrison, ‘“The only chance the Army of Northern Virginia had to save itself” – Jetersville, April 5, 1865’ (ECW Blog, April 5, 2015), https://emergingcivilwar.com/2015/04/05/the-only-chance-the-army-of-northern-virginia-had-to-save-itself-jetersville-april-5-1865/.

Following up on Orrison’s comment about Lee’s need to consolidate his forces, some historians persuasively argue that Lee had to stay at Amelia Court House in any case in order to concentrate his army. Nevertheless, Lee himself stated that he only stayed there as long as he did in an attempt to gather food supplies. The premise of this “what if” post takes Lee at his word.

A couple of more blood baths before the inevitable defeat.

The question(s) about the supply train that was supposed to be waiting for the Confederate army has always intrigued me. HOW did that happen? Lee appeared to have been led to believe that the train would indeed have the required and requested food supplies. So how did it come to pass that no such foodstuffs were included? Were orders conveyed that were ‘muddled’ in their language? Was a request or order sent that stated, say, a “supply train” was needed, as opposed to one asking for or ordering a “FOOD supply train” specifically?

Per that train that was sent to Amelia Court House that had only basic military supplies in it, where did it come from? Where were those particular supplies loaded at? Was that place bereft of food to send? Did someone just not get the memo? Was there any intrigue as far as intelligence or spy activities having an impact on what was requested vice what was loaded? It just seems so odd that such a colossal mistake could happen at such a dire time!

The question is indeed intriguing. Douglass Southall Freeman tackles the mystery in depth in his R.E. Lee: A Biography, Vol. IV, p. 66-68 & Appendix IV-2 (Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, NY, 1940). Jefferson Davis, apparently feeling implied criticism in Lee’s report that the expected supplies were not found, defended himself in Davis’s The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government (Thomas Yoseloff, New York & London, England, 1958), Vol. II, pp. 671-676.

Years ago, I read an article (which I would love to be able now to locate) that blamed the mishap on Lt. Col. Walter Taylor (effectively Lee’s chief of staff). You probably know that late on April 2, after Lee’s Petersburg lines have been pierced, and the evacuation of Richmond/Petersburg underway, with all the staff work and chaos that that effort must have generated, Taylor made a remarkable request of Lee. He wanted time off to travel to Richmond to get married. Amazingly, Lee granted the request. Taylor thus was absent from HQ for some hours at a most critical time. The author I read argues that Taylor had been responsible for ensuring that the supplies were sent to Amelia Court House, but he was too focused on his personal affairs. I do not recall the support for the author’s argument, but it is an interesting theory.

That is VERY interesting. Thanks..

Defeat for Lee would have still been inevitable and thousands of descendants would not be alive today.

The only difference would have been fewer hungry Confederates for a day or two and more of them in the bag wherever Lee surrendered — Appomattox or some other village nearby.

If the surrender had been delayed until after Lincoln’s assassination, the terms might not have been as generous.

Matt, that is an excellent point that I had not even considered. But of course you are almost certainly right.

What about Lee using the railroad to move his Army by rail?