Stacking Arms “What Ifs?” – Episode VI: “What If” the Army of Northern Virginia Had Opted for Guerrilla Warfare?

“Two thirds of us, I think would get away. We would scatter like rabbits & partridges in the woods, & they could not scatter so to catch us.” Confederate Brig. Gen. Edward Porter Alexander to Gen. Robert E. Lee, April 9, 1865, urging dispersal of the Army of Northern Virginia (ANV) for continued resistance.[1]

“Two thirds of us, I think would get away. We would scatter like rabbits & partridges in the woods, & they could not scatter so to catch us.” Confederate Brig. Gen. Edward Porter Alexander to Gen. Robert E. Lee, April 9, 1865, urging dispersal of the Army of Northern Virginia (ANV) for continued resistance.[1]

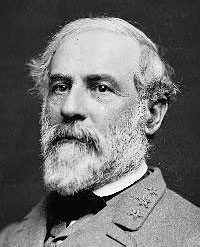

Lee refused to give his imprimatur to a guerilla warfare campaign. Citing a litany of reasons why Alexander’s proposal was infeasible, including that the men fanning out would have to steal to survive, and would cause U.S. cavalry to range far and wide bringing “fresh rapine & destruction,” Lee concluded that “while you young men might afford to go bushwhacking, the only proper & dignified course for me would be to surrender myself & take the consequences of my actions.”[2] In a few hours, the ANV would surrender in a body, rather than embark on an irregular campaign whose baleful effects Lee feared “would take the country years to recover.”[3]

In fact, the prospect that Lee and other Confederate commanders would turn to guerrilla, or “partisan,” warfare was a nightmare scenario haunting the minds of Union commanders, including Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman.[4] Indeed, Grant hoped that the generosity of his Appomattox terms would induce all remaining Confederate forces to surrender without dissolving into guerilla bands.[5]

Grant already knew the havoc irregulars could wreck. In August 1864 Grant had become so frustrated with Col. John S. Mosby’s success in savaging U.S. rear areas that he advised Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan to imprison the families of known Mosby men. As for Mosby’s forces, “Where any of Mosby’s men are caught, hang them without trial.”[6] A series of hangings and retaliatory hangings by Mosby followed before the practice stopped, but Union forces took to widespread destruction of civilian property, barns, grist mills, and animals to deprive Mosby’s forces of logistical support. And this all was sparked by a force that in early 1865 probably only numbered some 300 to 400 men.[7] What might happen if the same guerilla tactics were adopted by Lee’s men and perhaps then mirrored by other Confederate forces?

Although Lee had personally rejected the guerrilla option with Alexander and later written to Confederate President Jefferson Davis opining that “partisan war” would only cause further suffering without achieving independence,[8] Lee actually repeatedly threatened the North with the prospect. In an April 10 meeting with Grant, who sought Lee’s assistance in persuading the remaining Confederate forces’ surrender, Lee warned “that the South was a big country and that we might have to march over it three or four times before the war entirely ended.”[9] Furthermore, in a remarkable interview with a reporter from the The New York Herald, given two weeks after his surrender, Lee was even more blunt.[10]

In that interview, Lee declared that the South must yet be accommodated politically if the war were ever to cease, for if “arbitrary or vindictive or revengeful policies be adopted the end was not yet.” Lee warned “that the South could protract the struggle for an indefinite period,” bankrupting the nation. Lee predicted that the Southern people would resist “if extermination, confiscation, and general annihilation and destruction are to be our policy, [f]or if a people are to be destroyed they will sell their lives as dearly as possible.”

Could Lee have sparked a guerrilla war of any appreciable scope had he ordered the ANV to commence an irregular campaign? What if Lee had issued such an order?

Initially, it is reasonable to conclude that Lee personally would not have led the guerrilla resistance, for three reasons. First, as he told Alexander, Lee was “too old to go bushwhacking.” Even if he thought it right to order the army to scatter for continued resistance, Lee would surrender himself.[11] Second, and related to this first point, Lee’s compromised health made him a poor guerilla leader candidate.[12] Finally, Lee abhorred partisan warfare. Lee considered irregular units to be nothing better than marauders who caused more mischief (including depredations against Confederate civilians) than value and had opposed legislation allowing them to operate. Lee made an exception for Mosby’s unit, because Mosby maintained discipline, but even then had criticized that command for being too interested in plunder than proper military objectives.[13] It is inconceivable that Lee would have placed himself at the head of a partisan movement. As one historian has put it: “Guerrilla warfare simply was not in Lee’s DNA.”[14]

It also would have been nigh impossible for Lee to have implemented any considered guerilla strategy at Appomattox. There was simply no time left. Lee had not planned for his army to scatter; as of April 9, he still was hoping that the ANV could escape west. And, at the time Alexander made his plea, Lee was only minutes away from riding to a requested 10:00 a.m. meeting with Grant. While that meeting did not take place (Grant refused because Lee had wanted to discuss overall peace), Lee shortly thereafter met Grant in Wilmer McLean’s parlor and surrendered.[15] Practically, there was no time to get word to the troops to scatter, let alone disseminate an actual plan for them to follow.

But assuming Lee authorized Alexander to spread the word that Lee ordered his men to scatter and continue the fight as best they could, what then? Would the troops have heeded the call? Could they have? The remaining organized force of the ANV was hemmed in on almost all sides by federal troops, including Sheridan’s powerful cavalry corps. Had U.S. forces detected a last-minute mass escape attempt by disorganized Confederates, the result surely would have been an immediate assault and bloody slaughter prior to ultimate surrender of most of the survivors.

Still, some would have escaped. Indeed, many did. Even as Lee surrendered, much of his remaining cavalry escaped the federal cordon. On the night of April 8, Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee, Lee’s nephew and cavalry commander, had received the commander’s permission to leave the field if surrender were imminent.[16] On April 9, Fitzhugh and two of his division commanders led their troopers west. A column of twenty-eight artillery pieces from Richard H. Anderson’s division also made its way west to Lynchburg, Virginia. Other artillerists used their horses to flee. Hundreds of scattered infantry followed. By the close of April 9, thousands of soldiers had poured into Lynchburg. Many, although certainly not all, wished to continue the fight, either in Virginia or by joining Gen. Joseph Johnston’s Army of Tennessee in North Carolina.[17]

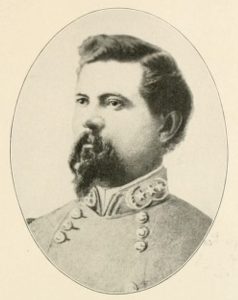

Such men received encouragement to continue the struggle. Stirring proclamations were issued by Confederate diehard leaders. These came from Maj. Gen. Thomas Rosser (on April 12 and April 28) and Col. Thomas T. Munford (April 21) as well as an earlier one (April 5) by Jefferson Davis. All sought continued resistance, urging troops to rally.[18] Rosser also concealed small arms and even some twenty artillery pieces.[19]

It was no use. While some men initially seemed willing to keep fighting as partisans-Rosser had assembled about 500 men by late April-[20] the reality of the situation was that thousands of individual soldiers from the ANV were streaming into federal provost marshal offices seeking the protection of the Appomattox parole. These men were spurred by war weariness and/or the sense that Lee’s surrender made further resistance futile, but also in some cases out of fear of U.S. reprisals if they failed to come in, especially after Lincoln’s assassination. One by one, the diehards’ leaders also gave up.[21]

Moreover, any possible thought of continued resistance was killed at the end of April by Johnston, who defied Davis’s orders and surrendered the nearly 90,000 men of his department to Sherman. Johnston even forced the diehard Lt. General Wade Hampton, in charge of a 5,000-man cavalry force, to stay and be included in the surrender.[22] Surrender of the remaining Confederate field armies followed.[23]

As shown, in assessing the question of “what if” Lee had directed the AVN to scatter and engage in guerrilla warfare, it can be said that in fact remnants of the ANV did have the opportunity to commence such a campaign. We thus need not stray too far into a “what if” exercise because in the end, the soldiers of Lee’s army declined the opportunity to turn to guerrilla war despite efforts from some of its leaders. Once Lee himself decided to surrender, any realistic chance for continued resistance on the partisan level evaporated.

Further, even if some survivors of the ANV had decided to carry on a resistance for any extended period of time the question would be, how logistically would they have survived? Lee was right; they would eventually have had to steal from the local populace to support themselves, depriving themselves of the very support guerrillas need. And to what end? Once Johnston surrendered, and especially after the political head of the Confederacy, Davis, was captured, the futility of further bloodshed was obvious.

Despite Lee’s bravado in his New York Herald interview, his April 20 letter to Davis revealed both an accurate observation as well as Lee’s true feelings: “A partisan war [could] be continued and hostilities protracted, causing individual suffering and the devastation of the country, but I see no prospect by that means of achieving a separate independence.”[24] His soldiers felt the same way, wanted to go home, and did.

[1] Edward Porter Alexander, edited by Gary W. Gallagher, Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander (The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC, 1989), p. 532; see also Edward Porter Alexander, “Lee At Appomattox, Personal Recollections of the Break-Up of the Confederacy,” The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, Vol. LXIII, New Series, Vol. XLI, November 1901, to April 1902 (The Century Co., New York, NY, 1902), pp. 921, 926-927, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.32106019606299&seq=931.

[2] Alexander, pp. 532-533.

[3] Alexander, p. 532.

[4] Caroline E. Janney, Ends of War: The Unfinished Fight of Lee’s Army After Appomattox (The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC, 2021), pp. 27, 45-46, 131, 206; William T. Sherman, The Memoirs of General W. T. Sherman, Vol. II, Chap. XXIII (D. Appleton & Co., New York, NY, 1876), pp. 344, 355, 362; Eric J. Wittenberg, We Ride A Whirlwind: Sherman and Johnston At Bennett Place, pp. 25, 67, 84-86, 104, 114, 119 (Fox Run Publishing, Burlington, NC, 2017).

[5] Janney, p. 27.

[6] The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Ser. I, Vol. XLIII, Pt. I, p. 811 (Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1880-1901) (hereafter “OR”), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.c035411746&seq=837; Janney, pp. 44-45.

[7] Janney, p. 45. An estimated 1,900 men at one time or another were members of Mosby’s 43rd Battalion of Virginia Cavalry (Mosby’s Partisan Rangers) during its roughly twenty-eight months of existence. Jeffry D. Wert, Mosby’s Rangers: The True Adventure of the Most Famous Command of the Civil War (Touchstone/Simon & Schuster, New York, NY, 1990), pp. 11-12.

[8] Clifford Downey & Louis H. Manarin, Editors, The Wartime Papers of Robert E. Lee (DaCapo, New York, NY, 1961), p. 939 (April 20, 1865, Lee to Davis).

[9] Ulysses S. Grant, Eds. John F. Marszalek, David S. Nolen and Louie P. Gallo, The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant: The Complete Annotated Edition (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2017), p. 727.

[10] The article is found at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030313/1865-04-29/ed-1/. Curiously, Lee’s interview was not considered front-page news, appearing on page five. The genesis of the interview, and discussion of Lee’s statements, can be found in Kevin C. Donovan, “The General In Defeat,” America’s Civil War (Nov. 2021). Note that the reporter, Thomas M. Cook, told his readers that he did not take contemporaneous notes; hence, direct Lee quotes within the article are sparse.

[11] Alexander, “Lee At Appomattox,” p. 927.

[12] For discussions of Lee’s failing health after the start of 1863, see e.g., Richard A. Reinhart, MD, FACC, FACP, “Robert E. Lee’s Medical History in Context of Heart Disease, Medical Education and the Practice of Medicine in the Nineteenth Century” (Originally published in 2016 in the Surgeon’s Call, Volume 21, No. 1), National Museum of Civil War Medicine (June 19, 2017), https://www.civilwarmed.org/surgeons-call/lee/; Rob Orrison, ‘“We Must Strike Them a Blow!”—Robert E. Lee at North Anna,’ Emerging Civil War (Three Parts, May 24, 2014), https://emergingcivilwar.com/2014/05/24/we-must-strike-them-a-blow-robert-e-lee-at-north-anna-part-one/#:~:text=Possible%20heart%20attacks%2C%20strokes%20and%20fatigue%20began%20to,in%201870%20was%20due%20to%20intermittent%20rest%20angina.

[13] Wert, pp. 138, 157; Virgil Carrington Jones, Ranger Mosby (EMP Publications, Inc., McLean, VA, 1987), pp. 173, 174).

[14] Chris Mackowski, “Lee and Guerrilla Warfare,” Emerging Civil War (December 7, 2017) (quote by Dan Davis), https://emergingcivilwar.com/2017/12/07/lee-and-guerrilla-warfare/.

[15] Douglass Southall Freeman, R.E. Lee: A Biography (Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, NY, 1940), Vol. IV, pp. 112-113, 120-138; Elizabeth R. Varon, Appomattox: Victory, Defeat, and Freedom At The End of the Civil War (Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 2014), pp. 34-37, 38-43, 49-59.

[16] Burke Davis, To Appomattox: Nine April Days, 1865 (Eastern Acorn Press, reprint by Publishing Center for Cultural Resources, New York, NY, 1992), p. 321.

[17] Janney, pp. 17-20, 35-42.

[18] Janney, pp. 49, 99, 107, 166; Jefferson Davis, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, Vol. II (Thomas Yoseloff, New York & London, England, 1958), p. 677. Rosser’s April 12 proclamation was issued from what he declared the headquarters of the Army of Northern Virginia. To increase his gravitas, Rosser gave himself a promotion, to Lt. Gen. Janney, p. 49. Munford’s proclamation (Special Orders No. 6) can be found at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=dul1.ark:/13960/t85h8bd46&seq=1.

[19] Janney, p. 206.

[20] Janney, p. 206.

[21] This story is told in fine and detailed fashion by Janney in her Ends of War.

[22] Wittenberg, pp. 115-116, 236-247.

[23] Trevor K. Plante, “Ending the Bloodshed: The Last Surrenders of the Civil War,” Prologue Magazine, Spring 2015, Vol. 47, No. 1, https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2015/spring/cw-surrenders.html.

[24] Downey & Manarin, p. 939 (April 20, 1865, Lee to Davis).

“Two thirds of us, I think would get away. We would scatter like rabbits & partridges in the woods,…” Reading Alexander’s words now, it’s interesting that he, an inveterate and maven hunter, would use prey animals in his description of his fellow potential guerrillas. Surely he knew what happens to rabbits and partridges. Thank you for an excellent article.

To be sure, Lee disapproved of guerilla warfare at the end of the war. Almost certainly this was out of concern for the civilian population of the South, which had been so badly abused by the Federal Government – 50,000 died of starvation, murder, and general deprivation during the war – and stood to suffer even more in reprisals due to guerilla warfare. As well, Southern infrastructure and farms had been wrecked and torched, and thus could not provide food and logistical support for a guerilla movement. He knew it would be a failure that would bring only more misery to the South. On the other hand, however, at the very beginning of the war, Lee, undoubtedly knowing the history written by his wife’s great-grandfather when he led the Continental Army to victory in the Revolution, as well as his own illustrious father’s hit-and-run cavalry exploits in that conflict, wrote that he would prefer to take the Confederate army “into the mountains” and from there could defy the Federal Government in a guerilla war that would never have ended. I can just feel it – cable series for five years about the Confederates fighting such a guerilla warfare, written by John Milius…but it won’t be on NetFlix.

The Klan and other anti-black violence in the Reconstruction era might be considered a type of guerilla warfare