Not all Cannon are Created Equal: Don’t Forget the Hundredweight

When thinking of small arms and artillery of the US Civil War, most gravitate toward the discussion of how rifling expanded effective ranges of fire. A rifled-musket could kill hundreds of yards away (or thousands if in the right hands in the right conditions) and rifled field artillery could be fired for miles. For weapons used in field armies, this is largely where the story of weapon range ends. However, for heavier guns, naval artillery and heavy artillery pieces housed in fixed fortifications, there is another factor that impacted range. Not all guns were manufactured equally, and a gun’s hundredweight could significantly expand its maximum effective range.

Firing Civil War era artillery involved numerous complex steps, relying on algebra, physics, and geometry to determine what cannon, projectile, and powder charge was appropriate at different ranges. The Union’s Elementary Instructions in Naval Ordnance and Gunnery, published in 1861 and used by naval officers on both sides, spent an entire chapter introducing principles of motion, inertia, density, and resistance.[1]

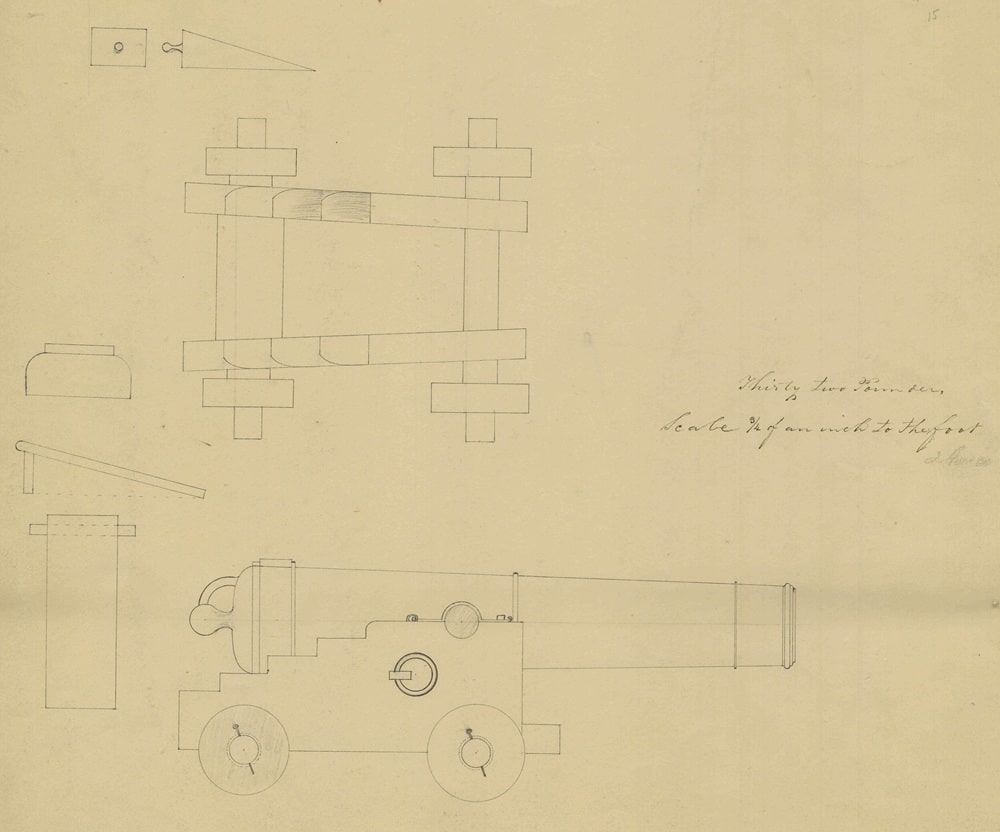

There were two ways to measure Civil War artillery, bore diameter of the barrel or weight of the projectile fired. For example, an 8-inch cannon had a barrel diameter of eight inches while a 12-pounder fired a shell or solid cannonball weighing 12 pounds. Essential to the effectiveness of the round fired was the gunpowder charge used to launch the projectile. A bigger charge – more powder – resulted in greater force and range. Elevation of a cannon’s barrel also affected range and the arc of the shot fired.

The other factor was the barrel’s weight, measured in what is called hundredweights, shortened to cwt in ordnance texts. In the United States, one cwt equaled 100 pounds. The British Imperial system however, measures one cwt as 8 stone, or 112 pounds. 20 hundredweights equals one ton in both the US and British systems, with the US system using the short ton and British using the long ton of measure.

The heavier the barrel (and greater the cwt), the more gunpowder charge could be used safely in the barrel, enabling a heavier projectile to fire at a longer range. Combine that with the question of whether artillery is smoothbore or rifled, and you have a conundrum that one 6-inch gun, for example, is not equal to another.

Being a naval historian, I will focus on one gun: the 32-pounder. This was the standard naval gun of the antebellum era. Throughout the 1850’s, the US Navy began phasing them out and replacing them with more modern Dahlgren shell guns. However, when the Civil War began, there were literally thousands of 32-pounders in the navy’s arsenal. Many ended up on early wartime blockaders and hundreds were captured and repurposed by the Confederacy when it captured the Gosport Navy Yard in Virginia.

A 32-pounder had a 6.4-inch bore diameter and fired a 32-pound shell. There were twelve different versions of the 32-pounder, with six different cwt measurements, ranging from 27 cwt to 57 cwt, plus variants for smoothbore and rifled barrels for each. The lighter 27 cwt 32-pounder used a gunpowder charge of four pounds, whose smoothbore variant could fire a shell out to 1,600 yards (nearly a mile). The heavier 57 cwt version of the same gun could absorb an explosive powder charge of up to nine pounds; its smoothbore variant had a range out to 2,700 yards.[2]

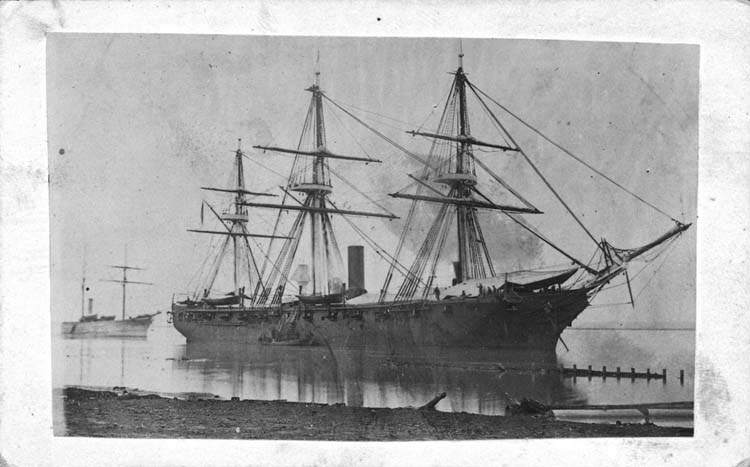

A small 1861 naval skirmish near the Mississippi River’s delta, occurred on October 9, 1861. It serves as an excellent example of the varying types of similar naval artillery in action.

In this skirmish, CSS Ivy, commanded by Lt. Joseph Fry, mounted a pair of 32-pounders brought to New Orleans from the Gosport Navy yard. One of Ivy’s guns was a smoothbore, while the other was a smoothbore gun converted into a rifled cannon in New Orleans only days before, meaning that second gun could shoot rifled 6.4-inch shells, not simply 32-pounder shot. Ivy’s rifled gun likely held a range of 2,100 yards, whereas its smoothbore 32-poounder could fire at a range of closer to 1,750 yards.

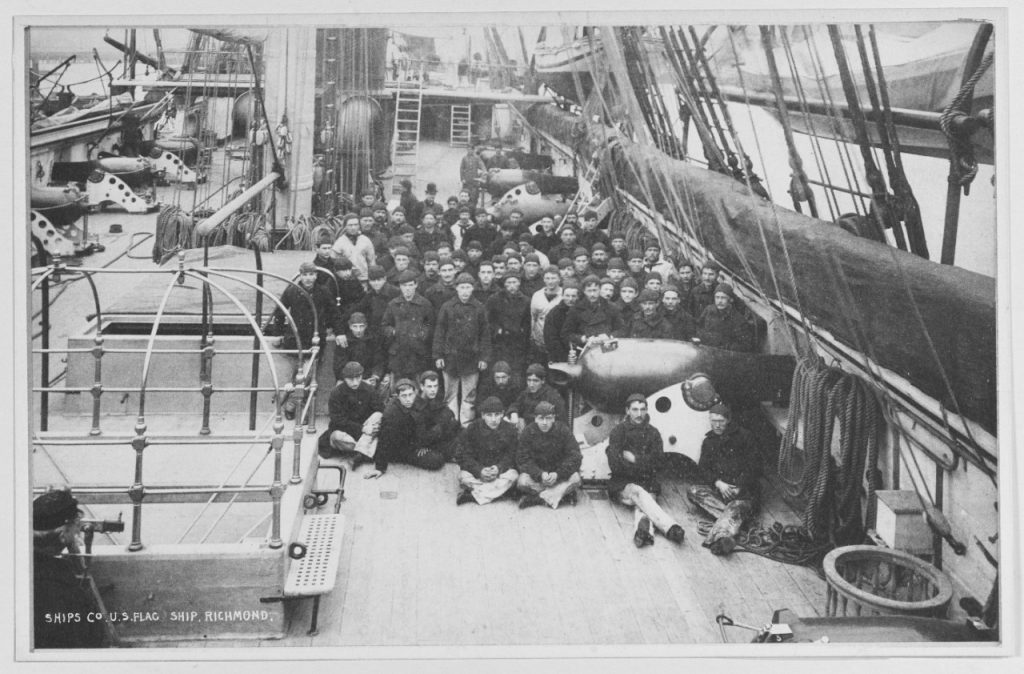

By comparison USS Vincennes, commanded by Cmdr. Robert Handy, carried four old smoothbore 68-pounders and eighteen antebellum 32-pounders forged at 33 hundredweight, meaning the barrel weighed 3,300 pounds; those guns had a maximum range of 1,598 yards. USS Richmond, led by Capt. John Pope (no, not that John Pope), carried 26 9-inch smoothbore Dahlgren shell guns, which had an effective range of 1,700 yards. There was also USS Water Witch, mounting four similarly light 32-pounders.[3]

Water Witch’s sailors first spotted Ivy steaming their way at 3:10 pm on October 9, 1861, but did not first think much of it, instead believing Ivy was only scouting their position. An hour later though, Ivy closed and opened fire with its rifled gun. Captain Pope ordered Lt. Andrew B. Cummings, his executive officer and a man who “had been shipmates” with Fry, to return fire.[4]

Sailors on both Richmond, Water Witch, and Vincennes rushed to man their guns. Lieutenant Fry, who spent years in the antebellum navy, knew his guns outdistanced the Federals, so he kept his distance. It quickly became obvious for all which gunners had the advantage.

USS Vincennes’s log highlights the disparity in artillery range well. “We fired 3 shot and 3 shell, all of which fell short. The steamers [Ivy] shot passed clear over us. The Commander [Pope] signalled [sic] us to hold our fire until nearer. he afterwards signalled [sic] ‘cease firing.’”[5] Vincennes’s Midn. Oliver Batcheller observed “some of her shot struck so close as to throw the water onto our decks.” Fry withdrew his little tug after an hour of firing and USS Water Witch briefly “gave chase.”[6] There were no casualties on either side. One newspaper account stated that in the bloodless skirmish Pope’s flotilla fired fifty shots at Ivy, and the Confederate tug fired ten in return.[7]

Federal sailors knew they were at a disadvantage. On Richmond, Acting Master Frederic Hill remembered Ivy made the day “lively for us. To be sure he never succeeded in hitting us, but it is very far from amusing to be potted at daily … with no opportunity of returning the compliment.”[8] In reporting the incident to his squadron commander, Pope claimed “we are entirely at the mercy of the enemy. We are liable to be driven from here at any moment, and situated as we are, our position is untenable. I may be captured at any time by a pitiful little steamer mounting only one gun. The distance at which she was firing I should estimate at four miles, with heavy rifled cannon, throwing her shot & shell far beyond us.”[9]

The October 9 example is but one of many in the Civil War where naval officers had to, on the fly, determine the range of an enemy’s guns, guessing what type of guns an enemy ship had, whether it was rifled, what hundredweight it was cast in, and how effective the gunners were – all while simultaneously maneuvering their own ships to counter and engage. Not all heavy guns were created equally, and that could prove the difference in who lived, who died, and who won a naval engagement or a siege on land.

Endnotes:

[1]James H. Ward, Elementary Instructions in Naval Ordnance and Gunnery (New York, 1861), 14-25.

[2]John A. Dahlgren, Shells and Shell Guns (Philadelphia, PA: 1856), 29, 32.

[3] J.D. Brandt, Gunnery Catechism, as Applied to the Service of Naval Ordnance (New York, 1864), 177-178; William H. Peters, “An Account of the Evacuation of the Navy Yard, First by the Federals in April 1861, and Second by the Confederates in May 1862,” William H. Stewart, History of Norfolk County, Virginia, and Representative Citizens (Chicago, 1902), Vol. 1, 451. Handy to McKean, Oct 28, 1861, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Vol. 16, 721.

[4] Frederic Stanhope Hill, Twenty Years at Sea: Leaves from My Old Log-Books, (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, & Company, 1893), 149.

[5] Oct 9, 1861, USS Vincennes Logbook, Logbooks of U.S. Naval Ships, 1801-1940, Record Group 24: Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1798-2007. U.S. National Archives.

[6] Oct 9, 1861, USS Water Witch Logbook, Logbooks of U.S. Naval Ships, 1801-1940, Record Group 24: Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1798-2007. U.S. National Archives.

[7] Batcheller to Parents, Oct 19, 1861, Oliver Ambrose Batcheller Letters, MS 264, Special Collections & Archives Department, Nimitz Library, United States Naval Academy; “Another Brush with the Enemy,” Daily True Delta [New Orleans, LA], Oct 11, 1861.

[8] Hill, Twenty Years at Sea, 149.

[9] Pope to McKean, Oct. 9, 1861, Gulf Squadron, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Commanding Officers of Squadrons, 1841-1886, Publication Number M89, Records Group 45, U.S. National Archives.

Neil, I think you need to bring a couple of these to the Symposium for a little live-fire demonstration. I’m sure Stevenson Ridge’s neighbors won’t mind.