Foul, Brutal, Savage, and Damnable: Quantrill’s Raid on Lawrence and the Pitfalls of Reciprocal Violence

ECW welcomes guest author Collin Hayward.

It is difficult enough to exercise the art of command under ideal circumstances, and ideal circumstances are rarely present in war. Those who can exercise the art of command well under difficult, chaotic, and trying circumstances often provide some of the best lessons on leadership.

Beyond the normal fog and friction of war that challenges any battlefield leader, practitioners of irregular warfare often find themselves confronting opponents who have inherent conventional advantages.[1] In addition to facing stronger opponents, the irregular commander often finds himself operating away from established military hierarchies, often in physical isolation from friendly forces. Because irregular warfare often involves directing one’s limited strengths against an adversary’s weaknesses to create some sort of asymmetric advantage, irregular commanders often engage in actions that are legally or morally dubious, such as attacks on soft targets in the enemy’s rear areas. This has historically incentivized irregular forces to engage in violence against civilians, and this risk is only enhanced by the desperation that comes with fighting a losing war. This essay explores how these dynamics shaped guerrilla leader William Quantrill’s infamous raid on Lawrence, Kansas and assesses what students of irregular warfare can learn from this raid and its aftermath.

courtesy of the Dover Historical Society

An objective assessment of Quantrill is difficult. He was a controversial figure during his lifetime, even among his fellow Confederates, but his case remains both instructive and relevant when exploring the dynamics at play in irregular warfare. Quantrill demonstrates the sort of contradictions that commonly manifest in guerrilla leaders; he demonstrated intellect, courage, and determination, but also became locked in a reciprocal cycle of retaliatory violence that drew increasingly little distinction between combatant and non-combatant.

Case Study

William Quantrill was a Confederate guerilla leader in the Kansas-Missouri border region. He had no professional military training, but quickly demonstrated a proficiency with violence in the raids and ambushes that characterized the war in that theater. He received a commission as an irregular cavalry officer in the Confederate army in 1862.[2]

Like many other Missouri “Bushwhackers”, Quantrill’s band primarily targeted irregular anti-slavery “Jayhawker” forces in a bloody guerrilla war that predated the Civil War. In this intercommunal violence, both the Jayhawkers and the Bushwhackers relied on extended familial connections to provide guerrilla bands with personnel, shelter, supplies, and information. This led both sides to target opposition family members and homesteads.

By spring 1863, the Union army decided to suppress Bushwhacker activity by imprisoning civilians suspected of supporting the rebels.[3] Many civilians that the Union arrested were female family members of the Confederate raiders, who believed that these arrests were disgraceful and barbaric, even by the standards of this guerrilla war.[4] When the building collapsed and killed several of the female prisoners, Quantrill planned and executed a raid designed to strike back at the heart of Union power in Kansas.[5]

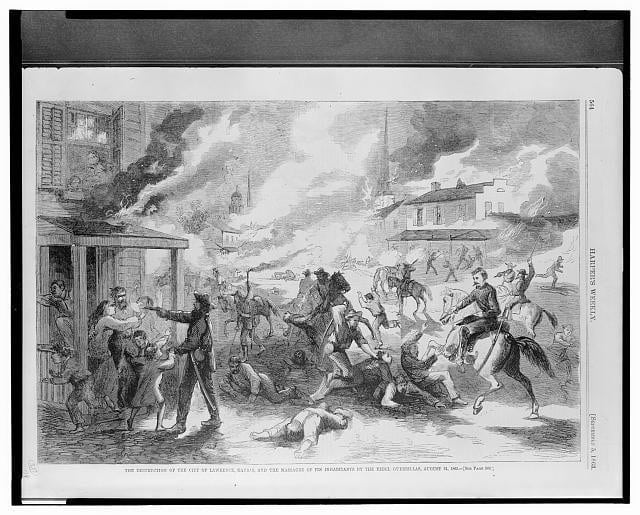

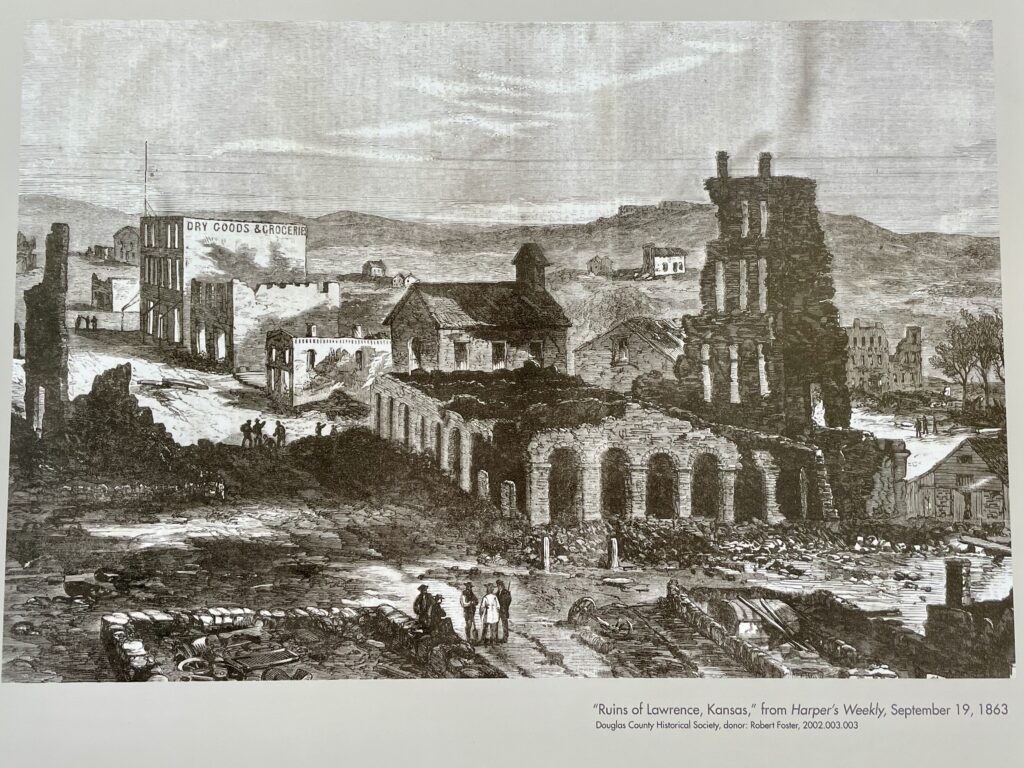

Quantrill assembled several different guerrilla bands and infiltrated deep into Kansas, where they attacked the city of Lawrence.[6] Quantrill’s raid burned much of the city and killed roughly 180 men.[7] Union cavalry pursued Quantrill, but his raiders fled and dispersed before they could be caught. The Union committed significant forces and carried out reprisals that effectively depopulated much of western Missouri, but was unable to suppress guerrilla activity, which continued throughout the war and persisted even years after the Confederate surrender.[8] Quantrill himself continued his guerilla activity until he was killed by a Union patrol in 1865.[9]

Analysis

Despite a lack of formal military training, Quantrill capably organized irregular forces and led them on complex and effective raids. Quantrill forced the Union to dedicate significant combat power to counterinsurgency efforts. He recognized that small groups of determined horsemen who were familiar with the physical and human terrain on which they fought could be agile enough to maneuver with relative freedom in Union-occupied territory. Their ability to assemble and disperse rapidly allowed them to mass against vulnerable targets and complicated Union efforts to defeat them. This forced the Union to instead employ harsh tactics that only made the civilian populace more supportive of the irregular rebel forces.

For Quantrill, the primary impediment to his decision-making was the emotional response to loss, namely the arrest and death of his soldiers’ female relatives. Due to their biases, Quantrill and his men assumed that the women had been killed deliberately, which one of his men described in a later memoir as a murder “in a most foul, brutal, savage and damnable manner” by “Kansas troops, calling themselves soldiers, but a disgrace to the name soldier.”[10] Quantrill viewed the women’s deaths as an escalation in a guerilla war that already made little distinction between combatant and non-combatant, and demanded revenge. Quantrill gravitated towards a solution that involved decisive action on his part. His experiences and biases led him to look for a vulnerable target against which he could launch a retaliatory strike.

Irregular warfare presents significant ethical challenges. Often the lines between combatants and non-combatants blur, irregular forces operating in the enemy’s rear are typically less able to care for prisoners, and the deeply personal nature of engaging in warfare in one’s own community often inflames the passions of the combatants to commit unethical acts. Quantrill is a useful example of a successful irregular leader whose organization was not ethically aligned. The war in Kansas and Missouri was particularly savage and often targeted the civilian population, and Quantrill was no exception to this rule. During his raid on Lawrence, he ordered his men to “kill every male and burn every house,” which he likely believed to be justified by the depredations of the Jayhawkers and the deaths of his men’s relatives.[11]

Though he achieved significant operational success, this raid and his other attacks on civilian targets delegitimized his force to such an extent that his men were regarded as little more than brigands and excluded from the protections offered to surrendering Confederate soldiers at the end of the war. Many of his men, like the James brothers and the Younger brothers, became outlaws. Although he achieved significant tactical and operational successes in his theater during the war, the ultimate degeneration of Quantrill’s command into banditry illustrates how inflicting and receiving the sorts of moral injuries common in irregular warfare can degrade and destroy the operational effectiveness of a fighting force.

Collin Hayward is an Army Officer and qualified Army Historian specializing in the study of irregular warfare. He holds a Bachelor of Arts degree from Virginia Tech and Master’s degrees from American University and the Army Command and Staff College, where he was an Art of War Scholar. He has previously published an analysis of historical case studies in the InterAgency Journal titled “How to Win Without Fighting: Cold War Lessons on the Risks and Rewards of Political Warfare in Strategic Competition”.

Endnotes:

[1] Headquarters, Department of the Army, ADP 3-05 Army Special Operations (Washington, DC: US Army, 2019).

[2] James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988). 785.

[3] McPherson, 785-786.

[4] John McCorkle and O. S. Barton, Three Years with Quantrill: A True Story Told by His Scout (Chicago, IL: Arcadia Press, 2016), 48.

[5] McPherson, 786.

[6] McCorkle and Barton, 51-52.

[7] McPherson, 786.

[8] Ibid.

[9] McPherson, 788.

[10] McCorkle and Barton, 50.

[11] McPherson, 785-786.

The author writes very well; he might consider a more extensive treatment of this very interesting subject.