“I Felt Sick at Heart and Discouraged”: A USCT Captain’s Combat Trauma at New Market Heights

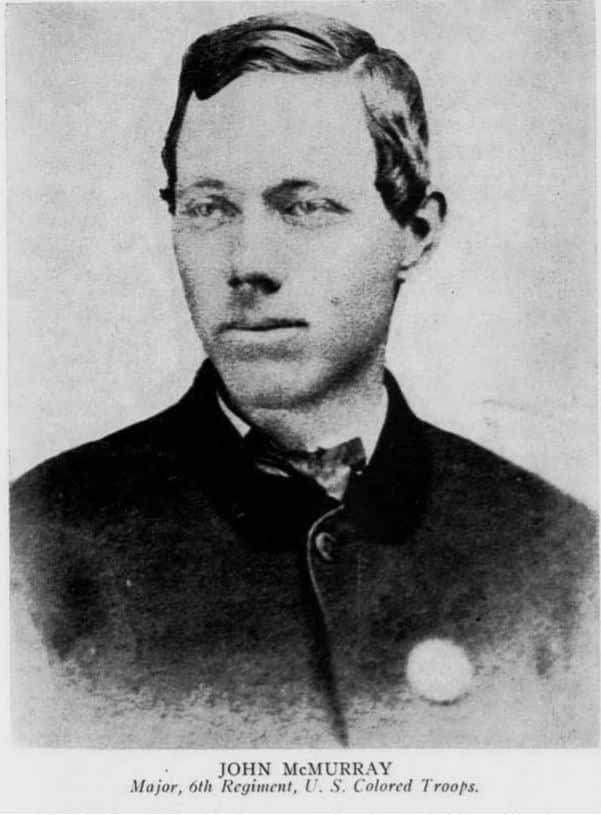

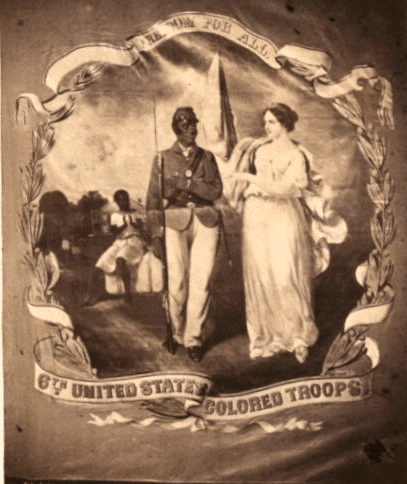

On the morning of September 29, 1864, Capt. John McMurray attempted to prepare himself and the 32 Black men that composed Co. D of the 6th United States Colored Infantry (USCI) for what he believed was to come. In doing so a wave of thoughts went through his and his men’s minds. “I know there was a big lot of thinking done by us while we stood there. We knew there was a strong line of Confederates behind the rifle pits, across the slashing from us. We knew that as soon as we would move forward they would open fire on us. We knew that the order to go forward would soon be given,” Capt. McMurray recalled years later. “But beyond that what? Would it be death, or wounds, or capture? Would it be victory or defeat? How the scenes and deeds of the past came rushing in on the mind like a mighty flood!” McMurray thought.[1]

With the aid of hindsight, McMurray saw the benefit of not knowing what exactly was to come. Sure enough, he had seen combat with his USCTs before, albeit limited. First, it was at Petersburg on the June 15, 1864, while fighting at Baylor’s Farm, and then later that day in attacking the Confederate Dimmock Line, successfully capturing a long stretch of earthworks and several artillery positions while assaulting with the other regiments that made up Brig. Gen. Edward Hinks’ USCT division in the XVIII Corps of the Army of the James.

However, concerning his New Market Heights experience, McMurray recollected, “Had I known when I arose that morning what was in store for my company, for my regiment, within the next two or three hours, I would have been entirely unfitted for the duties of the day. In [God’s] mercy and kindness I was allowed to see only what each moment revealed, and seeing that and that only, I went forward, trying to do the best I could, and hoping for the best results.”[2]

Like a number of other white officers for USCT units, McMurray had at least some limited military experience before joining the 6th USCI in September 1863. Born in 1838, in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, McMurray had previously served as a lieutenant in the 135th Pennsylvania Infantry, a nine-month regiment that mustered out following Chancellorsville. It was while serving briefly with a Pennsylvania militia unit near Pittsburgh following Gettysburg that McMurray developed an interest in serving in a USCT regiment. He went to Washington DC, passed the officer’s examination, and joined the 6th USCI, a regiment largely raised from Pennsylvania men that trained at Camp William Penn, near Philadelphia.[3]

At New Market Heights, the march from the 6th USCI’s brief campsite at Deep Bottom Landing to the Confederate position was about two miles. As they crested a hill to begin a descent toward the Four Mile Creek Confederate position, McMurray “noticed a score of [skirmisher] Johnnies scampering across the field before us, turning occasionally to shoot back at us.”[4]

Facing the assault the 6th and the 4th USCI was about to make were some of the Army of Northern Virginia’s best fighters. The Texas Brigade made up the center of the line at the point of the attack. To the left of the Texans were Virginia and South Carolina dismounted cavalry units. All were ensconced in earthworks which two lines of obstacles preceded: one a line of slashing abatis, and the other a line of cheveaux de fries, all formidable impediments for the USCTs to navigate through to get at the enemy.

If that was not enough, each flank of the Confederate line received protection from artillery. Additionally, a signal tower on New Market Heights allowed the southerners to provide advance notice in order to concentrate soldiers at the assault point. Finally, Four Mile Creek, which bisected the defensive line at one point and then turned to run parallel with the line, along with its marshy banks, made the USCT’s assigned task a difficult one to say the least.

As the 4th and 6th USCI approached the Confederate position they stopped to adjust their lines. They had received orders to load their rifles, fix bayonets, but not place percussion caps on their weapons. Officers wanted the men to get through the two lines of obstacles and drive the enemy out of its position at the point of the bayonet before anyone fired. McMurray remembered that during this time, “not an enemy fired a shot at us. I have no doubt but they looked on with great interest, thinking no doubt, what a lot of fools we were.”[5]

At last, Col. Samuel Duncan, who commanded the tiny two-regiment brigade, ordered them forward. McMurray remember that they “as one man we plunged into the slashing. And I want to say for the honor of our regiment, and the whole brigade, I believe not a man turned his back toward the enemy.”

Private Emanuel Patterson was one of McMurray’s soldiers who probably did not want to be there, but was anyway. Patterson had reported sick to McMurray before they arrived at Deep Bottom Landing. Sent to the surgeon, the surgeon sent Patterson back as fit for duty. On September 29, Patterson again answered sick call, and McMurray again sent him to the surgeon, who again returned Patterson back to his company to join the attack. The next time McMurray recalled seeing Patterson was “as I was pushing on through the slashing. . . .” Here McMurray met Pvt. Patterson “suddenly, presenting one of the most terrible spectacles I ever beheld. He was shot in the abdomen, so that his bowels all gushed out, forming a mass larger than my hat, seemingly, which he was holding up with his clasped hands, to keep them from falling at his feet.” Looking back, McMurray wished he “had taken the responsibility of saying to him that he could remain in the rear.”[6]

In moving forward, one of McMurray’s lieutenants, John B. Johnson, was shot through the wrist while swinging his sword over his head and encouraging the men. McMurray explained that “we were utterly unable to protect ourselves in any way.” Noticing his ranks “getting thinner and thinner,” he thought some might have turned back and gone to the rear. But, no, they were constantly falling killed and wounded. McMurray passed “my First Sergeant, Miles Parker, shot through the leg. He was sitting down, and greeted me as I passed by, saying ‘Never mind em, Captain; I’ll get along alright.”[7] Sergeant Parker survived, but was out for five month while recovering.

Amazingly, three or four members of the color guard were still moving forward. As McMurray encountered them at a narrow spot of felled trees, “Involuntarily, almost, I passed to let the colors go ahead of me. I followed close after, and just when the last one of the men, carrying one of our flags—we had three—was right in the opening . . . he was shot through the breast, and fell back against me, almost knocking me over. The loss of his life there absolutely saved mine.”

After coming into an opening between the abatis and the Confederate earthworks, McMurray met his colonel, John Ames, who “was as cool, apparently, as though there wasn’t an enemy within miles of us.” Then McMurray saw Lt. Frederick Myer (Company B) “as he stood a rod or two to our left and in advance of us. As I was looking at him he was shot through the body—I think through the heart—and immediately being hit turned about and leaped toward the rear. When hit he was standing directly in front of a brush pile about two feet high and three or four feet across. When he turned he sprang directly over this, falling dead on the other side.”[8]

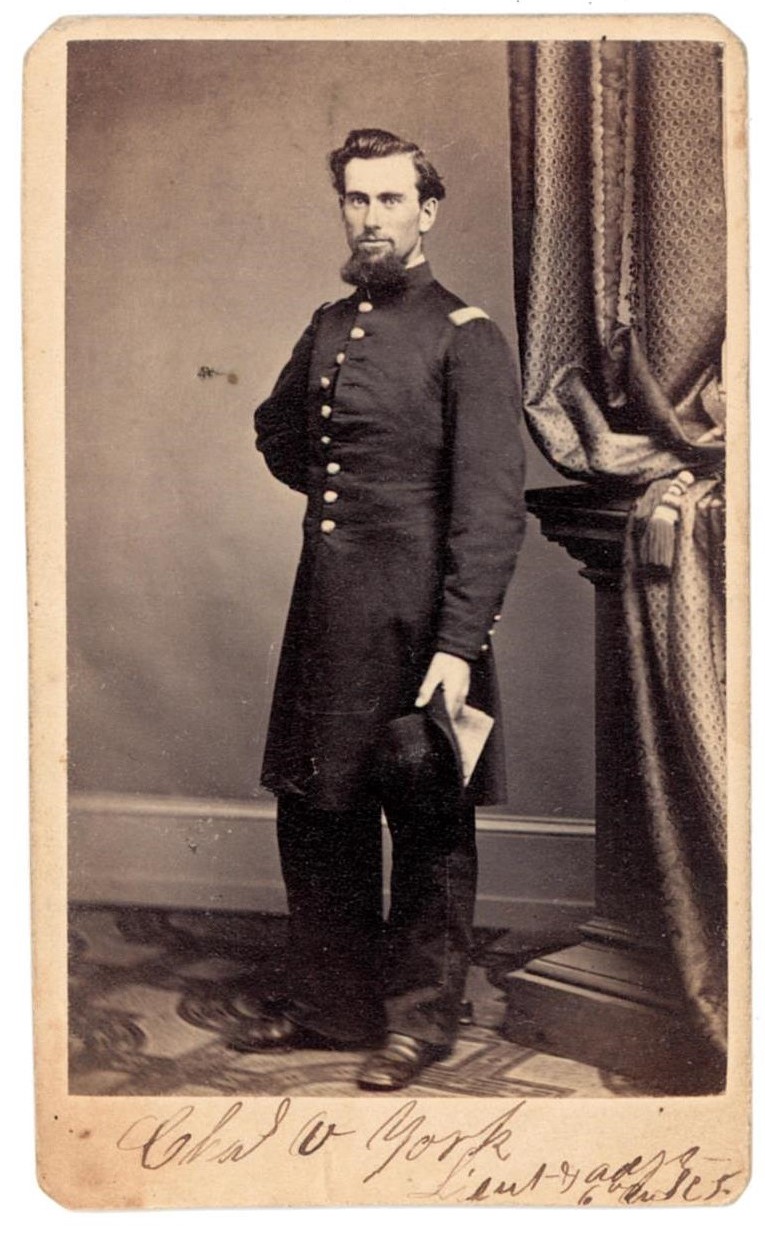

With Col. Duncan having been wounded, Col. Ames took command. Understanding the hopelessness of success with just two regiments, Ames suggested McMurray begin falling back, but to maintain as much organization as possible so as not to allow the men to become demoralized. Despite the horrific combat, the surviving enlisted men and non-commissioned officers apparently were still willing to remain and fight until ordered to stop. While going back through the lines of abatis, McMurray saw another fallen brother officer, Co. B’s Capt. Charles V. York, who was “lying by the side of a pathway, wounded and suffering terrible pain. He was unable to walk, and I could afford him no help. I noticed his surroundings and supposed I could go back to him.” After getting clear, and as “each officer began to collect his men,” McMurray found “I could find only three of my company, and wondered where all the others were. I had not yet learned what my loss was. When I learned it fully, I admit I felt sick at heart and discouraged.”[9]

The casualty count was astounding! McMurray’s company lost an astounding 85 percent of its men: 12 killed, 1 mortally wounded, and 14 wounded but who survived. The 6th USCI as a whole suffered over 55 percent casualties. The 4th USCI suffered similar losses.[10]

The second attack at New Market Heights, that of the 5th, 36th, and 38th USCIs, also took heavy casualties (over 30 percent). However, with their increased numbers and employing a column attack formation, they succeeded in dislodging the Confederate defenders.

After finding he had only three men left and also taking command of companies C and F, who lost all their officers, McMurray’s and the other regiments of the division pursued the Confederates as the southerners fell back to a line closer to Richmond. McMurray went back on the battlefield to find Capt. York. He found the path again, and the familiar location, “but the man seemed to be gone. I was puzzled.” Finally, after more searching, McMurray “noticed a body that had been stripped of all its clothing save undershirt and drawers. Close observation showed it to be” York. “His uniform, a good one, had been taken by the Johnnies, with all he had about him, including the money in his pocket, his watch, and other things in his pockets, and a paper on which was written his name, rank, and regiment, was pinned to the bosom of his shirt.”[11]

The dreadful sites continued for McMurray. Killed at Four Mile Creek was Capt. George Sheldon of Co. H. Until making a closer inspection, McMurray could not find a wound. At last “we noticed a small hole in the back of his neck, just at the base of the brain.” Shelton was probably shot through the mouth, likely shouting encouragement to his men, and bullet came out the back of the neck severing his spinal cord at the brain stem. McMurray also located all of the dead of his company, but unfortunately had to leave them there to push on and catch up with the rest of the division.[12]

Arriving at Fort Harrison, which had been captured by the two white divisions of the XVIII Corps earlier in the day, the remnants of the 6th USCI manned the line during a Confederate counter attack. While doing so, McMurray spied a large fresh USCT regiment, one “looking as though it had not seen any service.” An obvious sign was they were carrying everything they had. One man stood out, “a short, stout fellow, who seemed to be carrying a heavy load.” Seeing he was struggling to keep up, some of McMurray’s men jeered the soldier. Just then, “a shell from the enemy’s batteries struck him square and full, and scattered him, and his gun, and canteen, and haversack, and knapsack, all over the field. Looking at him, he and his belongings seemed to go in a hundred directions. Right there was engraved on one of memory’s pages a picture never to be effaced,” McMurray explained.[13]

After helping repulse the Confederate counterattack, the 6th USCI was pulled from the line to find a camping spot. McMurray found an abandoned Confederate hut that he called “comfortable.”[14]

That night McMurray fell into a depression. “What my feeling were after that days work, I will not attempt to state. They were somewhat sad and gloomy, I admit.” They were far beyond “sad and gloomy.” Taking stock of his company and regimental losses that fateful September 29, 1864 day, and having “not an old-time friend to go to. My heart sank away down toward my shoe soles, and sometimes it was hard enough to keep the tears back. I did think of home and the dear ones there, and wished the war would soon end.” However, McMurray was sinking fast toward a low spot. After having some food, he “began to have a strange, unusual feeling, a feeling of great oppression. I experienced a tingling, prickly sensation, as though a thousand little needles were jagging my flesh. The air seemed oppressive, and I breathed with difficulty. I couldn’t remain in the hut, and felt I must be out in the open air. So I went out to get relief, and spent a good portion of the night walking round and round the little building.”[15]

Unfortunately, the worst was yet to come: “After a while I became wild, almost crazy, and had to be looked after by those near me.” Comrades sent for the regimental surgeon. Administered what was probably an opiate, McMurray finally was able to get some rest and was ordered to the “corps hospital, where I remained ten days,” then he went back to his company. It was the only time he was away from this regiment in his two years of service with the 6th USCI.[16]

McMurray came to believe that his breakdown on the night of September 29, 1864 was because “the strain on me was so great through the day, that when the excitement passed over and quiet came, my nervous organization broke down temporarily. That was all.” After some rest and medicine, he felt his youth and strength helped restore him.

And yet, his combat trauma never totally left him. He explained his extended ordeal: “But I have suffered more or less every year of my life since from that day’s experience.” Any time he would exhaust himself, either physically or mentally, it “would bring me back to the place where I was that September night. On three different occasions, if not four, I have been brought back to where I was that September night in Old Virginia, and have borne it all with a mighty small amount of sympathy from those about me.”[17]

Combat-induced emotional trauma was not well understood until far into the twentieth century. The burden of friends and family not understanding what was the matter with McMurray must have been crushing to him. But suffer he did, as he tried to explain, “Soldiers have lost a leg or an arm and never suffered as much as I have done from the breaking down of my nervous system. . . .”[18]

Before mustering out, McMurray received a brevet promotion to major. Following the war, John McMurray resided in Jefferson County, Pennsylvania. His wife, Harriet Ann, whom he married in 1857 and had three children with, died in 1869. McMurray remarried in 1871 to Mary Jane Hall, and the couple had two children, both of whom died in childhood. McMurray died on September 4, 1920 at age 82, finally leaving the torturing memories of the battle of New Market Heights behind him.[19] Rest in peace, Maj. McMurray.

Sources:

[1] John McMurray, Recollections of a Colored Troop, The McMurray Company, 1994 reprint (originally published in 1916), 52.

[2] McMurray, 51.

[3] McMurray, 1; Compiled Military Service Record for Capt. John McMurray, Co. D., 6th USCI, accessed via Fold3.com, July 13, 2025.

[4] McMurray, 51

[5] McMurray, 52.

[6] McMurray, 52; 51.

[7] McMurray 53-54.

[8] McMurray, 54.

[9] McMurray, 54-56.

[10] McMurray, 55; Also see https://battleofnewmarketheights.org/6th-usci-casualty-list/ for a casualty list collected from the CMSRs of the 6th USCI.

[11] McMurray, 56.

[12] McMurray, 56-57.

[13] McMurray, 59-60.

[14] McMurray. 61.

[15] McMurray, 61.

[16] McMurray, 61-62.

[17] McMurray, 62.

[18] McMurray, 62; James M. Paradis, Strike the Blow for Freedom: The 6th United States Colored Infantry in the Civil War, White Mane Books, 1998, 96-99.

[19] McMurray, 105-108.

The mission of the Battle of New Market Heights Memorial and Education Association is to commemorate and educate. We seek to erect a monument at the site of the Battle of New Market Heights honoring the United States Colored Troops who served in the Third Division of the XVIII Corps (Army of the James). Among these men were fourteen African American soldiers and two white officers who received the Medal of Honor for acts of heroism on September 29, 1864. We also seek to educate the public about this significant military victory by the United States Colored Troops. More information is available at https://battleofnewmarketheights.org. As part of a collaboration between ECW and BNMHMEA, this piece is cross-posted at their website.

I believe that 1920 is the correct year of death, not 1890. Great article!

Thank you for catching that typo. I’ve corrected it.

Good article In addition to the direct combat trauma that McMurray experienced in and around Deep Bottom he and his men were tasked with recovering the remains of the fallen from the First Maine Heavy Artillery at least ten days after their charge on June 18, 1864. He described it as one of the saddest affairs. It all contributed to his trauma.

Yes, thank you Tim for a great article that brings to light the trauma experienced by the troops, as exemplified by this poor fellow.

Nice piece, Tim. Always solid!

I hope his children provided him solace.

An outstanding article. Thanks. To think his story is but one of so so many is truly hard to fathom. The personal accounts of these men are the ones that I most appreciate and gravitate to.

Excellent write up of a sad truth – may we remember their names.