USS Camanche’s Construction Odyssey

When it comes to the Civil War, there was a recognized industrial advantage the United States held over the Confederacy. The loyal states had more factories, railroads, shipyards, and natural resources fueling industrial output. The Confederacy had these things, but in fewer numbers. As the war continued, the United States never had problems arming its soldiers or keeping them relatively supplied. Warships were constructed at record pace, including dozens of ironclads. That does not mean that the United States was impervious to gross delay and unforeseen challenges. USS Camanche, a Passaic-class ironclad monitor, provides a great case study in the traditional challenges of getting a ship to sea, as well as how the unforeseen can significantly inhibit construction programs.

If you have not heard of USS Camanche, there is a reason. It did not besiege Charleston, enter Mobile Bay, or conquer the Mississippi River. In fact, depending on what you use as a measuring stick, it was not even commissioned as a warship during the Civil War. That was because of its mission, and the odyssey it underwent to be constructed, launched, and commissioned.

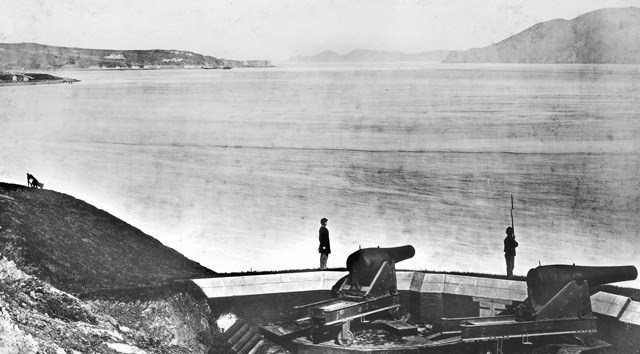

The Passaic-class monitors were built following USS Monitor’s performance at the battle of Hampton Roads. Folling that battle, John Ericsson made numerous improvements on the overall design and the Navy Department ordered ten of these. They were intended to lead assaults against Confederate ports. For example, seven of the ten participated in the failed April 1863 ironclad assault against Fort Sumter. Camanche was not among those however, as its mission was not to assault Confederate ports. Instead, it was envisioned to guard San Francisco.

Camanche was constructed by Secor and Company, a shipyard in Jersey City, New Jersey, for the sum of $613,164.98. Built in 1862, it immediately ran into a problem. Since Camanche was allocated to California, it was deemed less of a priority. When the Passaic-class monitor Weehawken’s engines failed in testing, replacement machinery was “commandeered right out of Camanche’s nearly completed hull.”[1]

Finished by early 1863, there was another problem. The only way to get to San Francisco was to bring it down around South America, and then up the Pacific coastline to California. The journey of thousands of miles was not something anyone looked forward to, especially considering USS Monitor foundered in a storm off North Carolina in December 1862. The small ironclad, only 200 feet long and displacing some 1300 tons, it was only 40% of the length and 15% of displacement of a modern Arleigh Burke class destroyer. It would never survive the trip.

There was a solution! Though, it meant going back to square one. Camanche would get to San Francisco, but not on its own. Instead, the completed ironclad was disassembled piece by piece. The separate parts were loaded in crates onto the merchant ship Aquila, which would make the journey. Detailed reassembly instructions were prepared, turning the ironclad into the equivalent of a massive Civil War Lego project. But if things went well, the ship would be assembled and ready for battle by early 1864.

The need to protect San Francisco was apparent. In March 1863, as Aquila was preparing, Confederate sympathizers were captured in San Francisco Bay. The group had purchased the sailing vessel J.M. Chapman, collected a crew, and were preparing to take the vessel to sea as a Confederate privateer. Thanks to good intelligence-gathering, Chapman was seized the morning of its departure by sailors from USS Cyane, port officials, and San Francisco police officers. Though the privateering threat was eliminated, desperate calls to boost the bay’s defenses grew in furor with each passing day. Cyane’s captain was advised to exercise increased caution in guarding the bay: “While at anchor you must guard against sudden surprise, particularly from steamers at night, drilling your men so that they may be prepared at a moment’s notice to come on deck with arms ready, without the delay of dressing.”[2]

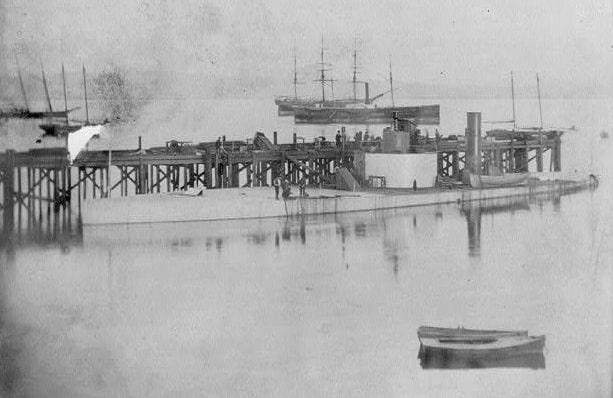

Aquila’s arrival was highly anticipated, but it took 166 days for the ship to reach California. The steamer’s master had special instructions “to sink his ship” if Confederate raiders “hove in sight, and thus prevent the rebels from capturing a most dangerous and valuable prize.”[3] The ship encountered no enemies however, and reached San Francisco in November 1863.

Disaster struck again when a heavy gale hit San Francisco Bay on November 15, 1863. There were some reports that a British ship got loose and rammed Aquila. Others said the cargo ship smashed against the wharf. Regardless, Aquila sank “with only about twenty-five feet of the after-hull and deck visible, the sea sweeping through and over her decks.”[4] In efforts to contain the situation, Aquila was “made fast to the dock by chain cables, to prevent her listing seaward.”[5]

There were disagreements about how to recover the ship and its precious cargo. Many proposed building a cofferdam around the wreck and pumping water out, while one interesting proposal was to “raise the Aquila by the use of balloons.”[6] Admiral Andrei Alexandrovich Popov, commanding Russia’s Pacific Fleet, then anchored in San Francisco, kindly “tendered the services of a large number of his men to assist in raising the Aquila and saving the Comanche [sic].”[7]

A San Francisco diving crew was hired to see if Aquila could be refloated and recover the disassembled ironclad’s parts. By the end of 1863, $30,000 had been spent in efforts to do so, but to no avail. By then, the divers were put on pause because insurance underwriters demanded to send their own team of divers to supervise. Thus, raising Aquila was temporarily abandoned, as newspapers chastised that “Comanche [sic] must rest in her slimy bed, at the bottom of the bay.”[8]

A special team of ten wreckers and four divers was dispatched from New York. The team, directed by Captain I.E. Merritt, reached San Francisco about January 22, 1864. Merritt, who “had much experience in … this business,” was given ten months to salvage Camanche’s parts.[9] After taking time to do surveys and develop a plan, the team set to work.

They made good time. Smaller crates of iron plating, pipes, and miscellaneous material was recovered first. In early April, Camanche’s pilothouse was recovered. By the end of April, the ship’s pair of XV-inch Dahlgrens were recovered. Camanche’s final piece, its boiler, was recovered on June 15. Instead of taking ten months to get everything turned over to the navy, Merritt’s team took five. Aquila’s wrecked hulk was moved and ultimately sold in August 1864.

Though everyone celebrated, it was still not a complete victory. The ironclad should have already been in commission, and the parts still needed to be cleaned, inspected, then reassembled. That took another three months.

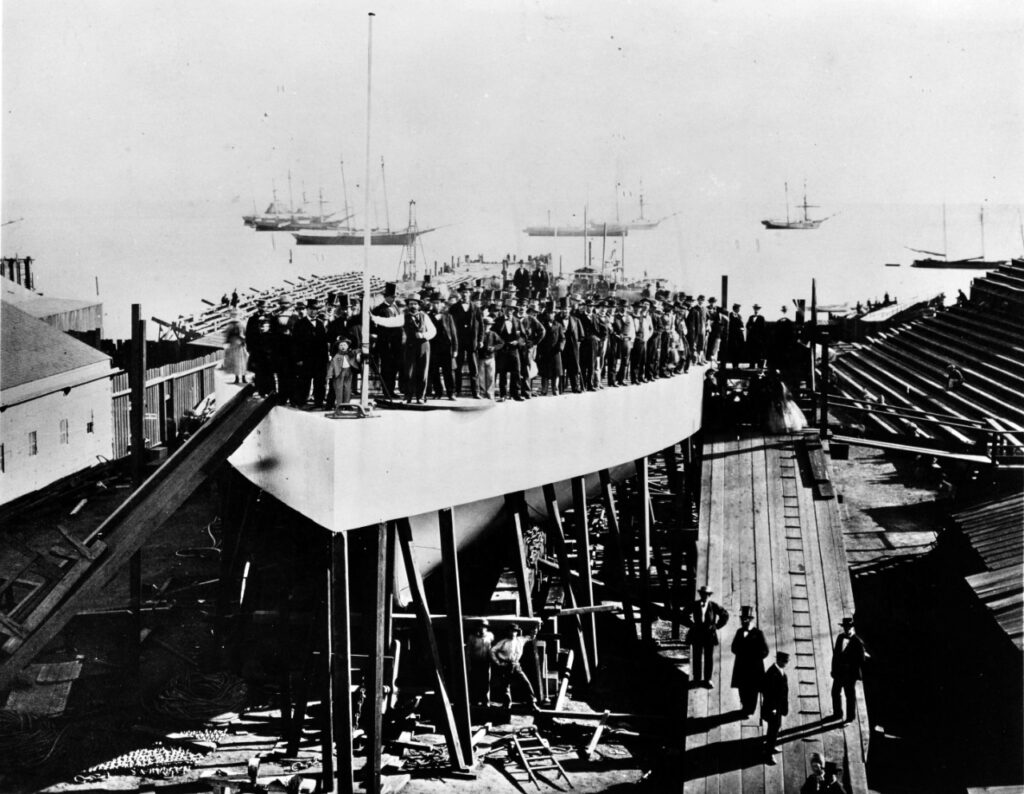

Camanche was officially launched on November 15, 1864, “in the presence of many thousands of spectators,” with the ironclad’s deck packed with officials, and with “hundreds of little boats” looking on.[10] The launching went off without a hitch (except some paint scraped off after it hit the drydock), one year and one day since Aquila first sank.

Outfitting took another six months, and Camanche was not officially commissioned as a warship until mid-1865. Many considered it just in time, as San Franciscans worried about the Confederate commerce raider Shenandoah.

On August 3, Navy Secretary Gideon Welles wired a short but clear message to California’s naval officers: “Shenandoah making depredations in Pacific. Department relies upon you to effect her capture.”[11] Camanche stood ready guarding San Francisco, should Shenandoah launch an attack. Instead, the Confederate raider, upon learning of other Confederate surrenders, disarmed itself and steamed to England to surrender.

Great pains were undertaken to get Camanche ready to fight, but it never fired its guns in anger. The ship remained in San Francisco Bay, and was disarmed and sold after the Spanish American War. It became a coal collier in the bay, a job Camanche continued doing until the 1930’s. Envisioned to defend San Francisco, it turns out that USS Camanche’s greatest trial was instead simply being built.

Endnotes:

[1] Jesse N. Bradley, U.S.S. Camanche: The Snakebit Monitor, The Retired Officer, May 1978, 21.

[2] Bell to Shirley, 22 Sept 1863, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Vol. 2 461.

[3] “The Navy,” New York Herald, November 13, 1863.

[4]“The Wreck of the ‘Aquila,’” Harper’s Weekly, January 16, 1864.

[5] “On Sunday Night Last,” The Placer Herald, Auburn, CA, November 21, 1863.

[6] “Somebody at San Francisco,” Marysville Daily Appeal, Marysville, CA, December 9, 1863.

[7] “Russian Courtesy,” Santa Cruz Sentinel, Santa Cruz, CA, December 5, 1863.

[8] “A Santa Cruzan in San Francisco,” Santa Cruz Sentinel, Santa Cruz, CA, December 12, 1863.

[9] “To the Rescue of the Aquila,” The Contra Costa Gazette, Pacheco, CA, January 23, 1864.

[10] “Launch of the Camanche,” Marysville Daily Appeal, Marysville, CA, November 16, 1864.

[11] ORN, Series 1, Vol. 3, 576.

The Impending Crisis in the South, How to Meet It by Hinton Rowan Helper explains two nations formed at the same time. Plymouth in 1620 and Jamestown in 1607. By 1850, one was wealthy and the other one poor.

My, what a tortuous trail for that ship.

Thanks Neil … I had read about the San Fran ironclad, but always saw the name spelled COMANCHE, like the Indian tribe … thanks for the correction … I also believe it’s bad luck to construct a vessel, albeit not yet commissioned, and then deconstruct it and build it again … and CAMANCHE certainly had more than her fair share of poor fortune … thanks again for this little known Navy tale!

Hey Mark. Yea, the other spelling is commonly seen, but the ship’s actual records and documents show the ‘a’ instead of an ‘o’ The name is intended to honor the indigenous group, but the folks completing the paperwork spelled it as Camanche. It is one of those ‘Does Merrimack’ had a K at the end, or does USS Pittsburgh have an ‘h’ at the end’ issues. Often the spelling made 30 years after the war when the OR/ORN were written became what a ship was referred as, even if at the time of the Civil War it was different.