A Lost Blanket Tells the Story of Two Divided by the Civil War

ECW welcomes guest author Michael A. Musilli.

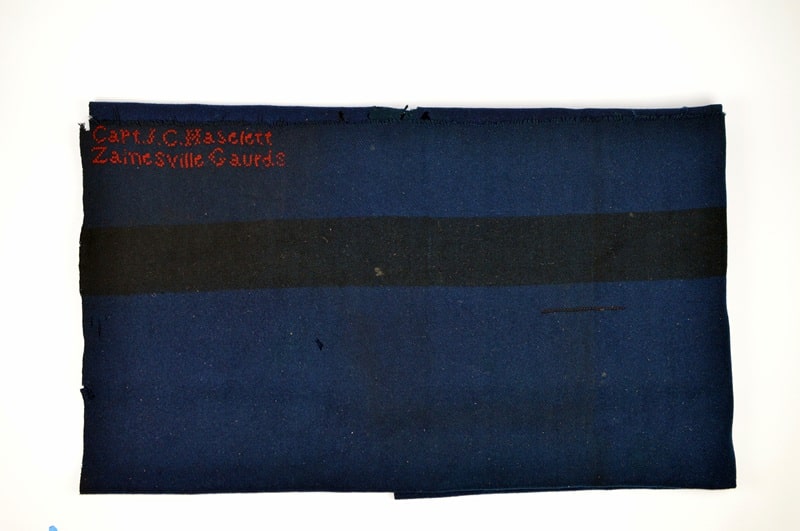

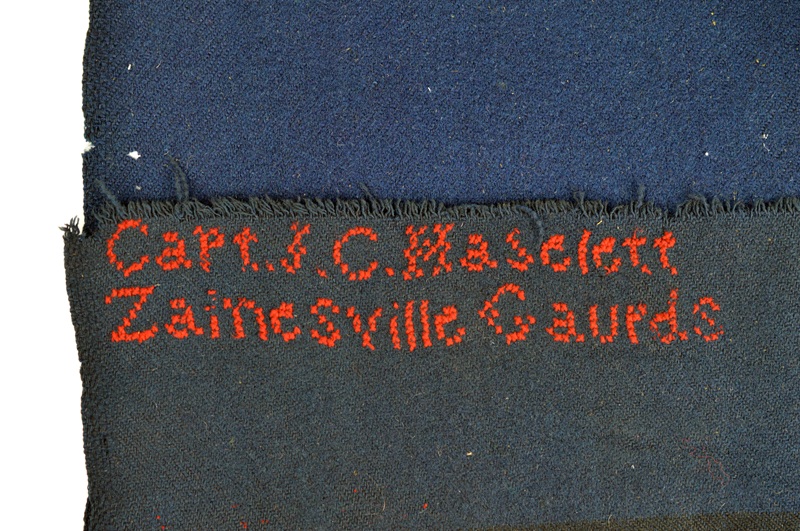

In May 2011, members of the Muskingum County Civil War Association based in Zanesville, Ohio dedicated new tombstones they commissioned to replace the broken memorials of two local veterans. The first soldier was Lt. Charles Edward Hazlett, the well-known artillerist from Zanesville mortally wounded on Little Round Top in July 1863. The second was Capt. John Caldwell Hazlett, his older brother, who raised and led an infantry company nicknamed the Zanesville Guards during the war’s first three months. While working to replace the stones, members of the association found a perplexing artifact in the collection of the American Civil War Museum in Richmond, Virginia. It was a dark blue, wool blanket with black bands, and the misspelled identifier “Capt. J.C. Haselett,” “Zainesville Gaurds” stitched in red lettering on one corner.

Association members had little doubt the blanket belonged to their Capt. Hazlett. But other questions did not have clear answers. Why were his name and unit misspelled, and why was the blanket in a museum in Richmond, Virginia of all places? Further research revealed an unexpected story.

When Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 troops buzzed across telegraph wires in Zanesville, Ohio in April 1861, twenty-nine-year-old John Caldwell Hazlett became one of the first men in the state to receive a captain’s commission and raise a company of infantry volunteers. He was well-positioned for the role. A graduate of a small military school in Kentucky, the brilliant young lawyer was also the captain of a local militia and Muskingum County’s prosecuting attorney.[1]

Locals knew him for his oratory and political views. A loyal Republican, he led a local Wide-Awake club for Lincoln in 1860. A year earlier, he had unsuccessfully defended a fugitive slave from extradition to Virginia.[2] Positions like these made him unpopular with locals who disagreed with his opinions.

Hugh Thomas Douglas was one such man. A native of Alexandria and Warrenton, Virginia who came from a slave-holding family, Douglas was well-acquainted with Hazlett. His younger sister Rebecca was married to Hazlett’s older brother, William.[3]

The Douglas family settled in Zanesville in the 1850s. A civil engineer by trade, Hugh completed railroad projects with his father, then patented and sold his own sugar mill from a family-owned foundry and machine shop.[4] But even though his sister Rebecca married into the Hazlett family, and other siblings became fond of their new home, he remained sympathetic with the southern states. He married a Virginian – she died the following year – and he was enraged when Lincoln called for volunteers to suppress the southern rebellion.[5]

He called Ohio a “hotbed of Abolition” and told John Hazlett he should move to Virginia. Hazlett replied that he would go, but it would be “with gun in hand, to crush the rebels.”

“If you come on such an errand,” Douglas supposedly retorted, “I predict you will run away.”[6]

Both men soon left Zanesville. Douglas returned home and joined Capt. Delaware Kemper’s Alexandria Light Artillery as a private.[7] Hazlett raised the Zanesville Guards – later designated Company H, 1st Ohio Volunteer Infantry – said goodbye to his wife and son and took the railroad to Columbus. Shortly thereafter, the Guards departed Columbus for Washington.[8]

Being that they left Ohio within days of enlisting, the company’s uniforms and equipment arrived piecemeal. One enlistee wrote home that each man received a blanket somewhere enroute to Washington, possibly from authorities in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania during a layover there. A letter from another man reveals why the blanket contains misspellings of Hazlett’s name and unit identification. During a subsequent stop in Lancaster, “young ladies” in the town provided the Ohioans with shirts and pants. They also “worked [their] names on [their] Blankets with crewel.”[9]

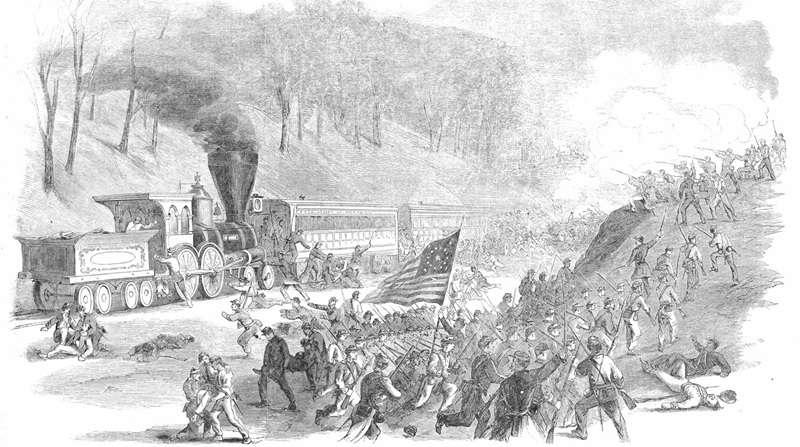

Two months later, Capt. Hazlett and his men finally “saw the elephant.” On June 17, 1861, the 1st Ohio crammed onto flatcars and crept along the Alexandria, Loudon, and Hampshire Railroad into the Virginia countryside to relieve other troops. As the track bent through a cut in the terrain near a village called Vienna, gunfire exploded from a parallel embankment. The Ohioans leapt from the cars and returned fire before escaping, but three of Hazlett’s men fell dead or suffered mortal wounds; several others were injured. A force composed of South Carolina infantry, some cavalry, and two guns of the Alexandria Light Artillery – the very unit in which Hugh Thomas Douglas served – had caught them by surprise.[10]

Private Douglas surveyed the scene after the ambush. Finding a blue blanket dropped in the woods by Hazlett’s camp servant, he saw a familiar name stitched in red on one of its corners.

“Capt. Hazlett’s negro lost his blanket in the engagement;” one of the Guards wrote home after the skirmish. “[T]he President of the railroad told the Captain than [sic] a man by the name of Tom Douglas told him that he had Capt. Hazlett’s blanket, and would have him before long…”[11]

“We expect to have a grand engagement with the rebels soon,” wrote another of the Guards, “and if possible we will capture Traitor Douglas, and if we do we will have some rope in the Regiment.”[12]

John Caldwell Hazlett and Hugh Thomas Douglas never met again. Hazlett returned home and raised another company after his unit’s three-month enlistment ended. Plagued by illness and alcoholism, he suffered a debilitating wound at Stones River and died at age thirty-one on June 7, 1863. Weeks later, his twenty-four-year-old-brother, 1st Lt. Charles Edward Hazlett, died at Gettysburg.[13]

Hugh Thomas Douglas received a captain’s commission in the 1st Regiment, Confederate Engineer Troops and served until summer 1864. In charge of mining at Petersburg, he refused an order to finish packing a tunnel with explosives because he did not believe it was his job. Authorities accepted his resignation in lieu of a court-martial. He resumed work as an engineer after the war and remained in Virginia, though some of his family stayed in Zanesville, and one of his brothers even served in a Unionist regiment raised in Tennessee. He died in 1891 at age seventy-two.[14]

Douglas apparently never remarried or had children, and items from his war service passed out of his family’s hands. The American Civil War Museum in Richmond eventually acquired the blanket, among other items he owned. An 1896 note contained in the artifact’s accession file says he captured the unassuming relic as “a prize of war, from an old friend at the battle near Vienna,” and used it “throughout the struggle between the states.”[15] Today, 160 years later, it remains preserved as a fascinating reminder of a nation divided by civil war.

Michael A. Musilli is a high school history teacher and native of southeastern Ohio. A biographical article that he wrote about John Hazlett’s brother, 1st Lt. Charles Hazlett, will appear in the next edition of Gettysburg Magazine. He would like to thank Robert F. Hancock, Senior Curator and Director of Collections at the American Civil War Museum in Richmond, Virginia, for information about the artifact featured in this article.

Endnotes:

[1] Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Muskingum County, Ohio (Chicago: Goodspeed, 1892), 196.

C.S. Williams, Williams’ Ohio State Register and Business Mirror, For 1857 (Cincinnati: C.S. Williams, 1857), 301.

[2] “AT A MEETING OF REPUBLICANS OF ZANESVILLE,” Zanesville Daily Courier, November 8, 1860; Christine Dee, ed., Ohio’s War: The Civil War in Documents, Civil War in the Great Interior (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2006), 26-28.

[3] 1850 U.S. Census, Schedule 2, Turners District, Fauquier County, Virginia (897 penned); “Married,” Zanesville City Times, May 3, 1856.

[4] Norris F. Schneider, “Brother of English Lord Established Residence in City,” Sunday Times Signal (Zanesville, OH) March 6, 1955; U.S. Congress, Senate, Report of the Commissioner of Patents for the Year 1860, Arts and Manufactures, 36th Cong., 2nd sess., S. Doc. 7 (Washington, DC: George W. Bowman, 1861) 1:619; “Douglas’ Improved Premium Sugar Cane Mills,” Zanesville Daily Courier, August 1, 1863.

[5] “Died,” Alexandria Gazette and Virginia Advertiser, August 24, 1854.

[6] “From Camp Pickens,” Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), June 24, 1861.

[7] Compiled Military Service Record of Hugh T. Douglas, Company F, 1st Regiment, Confederate Engineer Troops, Microfilm Publication 258, roll 0093, Record Group 109, National Archives, Washington, DC.

[8] Ohio Roster Commission, Official Roster of the Soldiers of the State of Ohio in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1866 (Akron, OH: Werner, 1893), 1:1, 14-15.

[9] William P. Gardner, “Letter from a Zanesville Boy,” Zanesville Daily Courier, April 25, 1861; Frank J. Van Horne, “From the Ohio Volunteers,” Zanesville Daily Courier, April 27, 1861.

[10] U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1880), ser. 1, vol. 2, 124-130; Ohio Roster Commission, Official Roster, 1:14-15.

[11] “The Battle at Vienna,” Zanesville Daily Courier, June 29, 1861.

[12] G.W.C., “Army Correspondence,” Zanesville Daily Courier, June 27, 1861.

[13] CMSR of John C. Hazlett, Company E, 2nd Ohio Infantry Regiment, RG94, NA; Ellen Hazlett Widow’s Pension, Application No. 25744, Certificate No. 22496, service of John C. Hazlett, Company E, 2nd Ohio Infantry Regiment, RG15, NA.

[14] CMSR of Hugh T. Douglas; “Death of Mr. Douglas,” Alexandria Gazette and Virginia Advertiser, March 16, 1891; “Death of John J. Douglas,” National Tribune (USA), July 28, 1898.

[15] Statement attached to letter of H.P. Baker to Mrs. J. Taylor Ellyson, June 15, 1896, accession file, catalog no. 0985.13.01322, The American Civil War Museum, Richmond, VA.

Thank you for a fascinating and well written piece. I throughly enjoyed it. Such odd things happen in war.

Very interesting article. Enjoyed it very much.

Fascinating. Everyone in those days knew everyone else.

I am guessing that Hazlett Ct. in Zanesville is named after them or their family.