“My Father is Here”: A Tragedy in the Civil War

ECW welcomes back guest author Riley Sullivan.

When one thinks of the American Civil War, they might be drawn to places like Gettysburg, Vicksburg, Bull Run, Fort Sumter, or Shiloh. These battles, and others, have been etched into the American psyche due to the tremendous consequences they wrought. Fewer individuals might consider that any significant action took place in Galveston, Texas during the Civil War. However, in the early morning hours of January 1, 1863 “the heavens were in a blaze” in Galveston.[1] On this battlefield, one of the most remarkable occurrences of the entire Civil War occurred.

Around 4 a.m. – hours before President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation – Confederate forces under the command of Maj. Gen. John Bankhead Magruder launched a joint sea-land attack against Union soldiers and vessels stationed in Galveston Bay. The fighting lasted throughout most of the early morning before Union troops of the 42nd Massachusetts surrendered while the Federal fleet sailed out of the bay. With the recapture of Galveston, the Confederates also boasted the destruction of USS Westfield and the capture of USS Harriet Lane. It was aboard Lane that a father and son, fighting on opposing sides, came to confront each other on the battlefield.

Harriet Lane’s executive officer was Lieutenant Commander Edward Lea, born to Albert Miller Lea and Ellen Shoemaker in Baltimore, Maryland in 1837. He grew up in what Adm. David Dixon Porter later described as “the very heart of Secessia.”[2] His father was a graduate of West Point (class of 1831) and served as an engineer on the frontier.[3]

Undoubtedly, his father’s military background influenced Edward’s own desire for a military career as he enrolled in the U.S. Naval Academy in 1851. After graduating in 1855, Lea served as a midshipman and later a lieutenant aboard USS Hartford in the East India Squadron.

While Lea served in the navy, his father moved to Texas and, with the outbreak of the Civil War, the Lea family endured a schism. For the elder Lea, there was no question as to which side to support. Being a Southerner, he, as well as most of the Lea family, opted to support the newly formed Confederacy.

Meanwhile Edward, despite being a “Southern man,” opted to remain loyal to the Union. Similar to the likes of Southerners like George Thomas, Edward later stated to then Cmdr. David Porter that because of his decision, “my family [has] disowned me.” In this same conversation, Edward also provided insight into how his father–who served as a Confederate artillery officer–stated that “if he should ever meet me in battle he would shoot me like a dog.”[4]

With this matter weighing heavily on Edward’s heart, he returned to Philadelphia in late 1861 to receive a new assignment.[5] On December 26, 1861, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles reassigned Lea to USS Harriet Lane; he reported by the end of the year. For the next year, Lea served as Harriet Lane’s executive officer, under Lt. Cmdr. Johnathan Wainwright.

After serving a brief stint in Virginia, Lea and Harriet Lane were attached to the West Gulf Blockading Squadron under then-Captain David G. Farragut. During 1862, Lea saw action throughout the Gulf, where he participated in the capture of New Orleans, Pensacola, and an attempt at Vicksburg’s guns. During this period, Harriet Lane served as the flagship of David Porter’s Mortar Flotilla. By late 1862, Harriet Lane reached its final assignment as a Union vessel, blockade duty off Galveston, Texas.

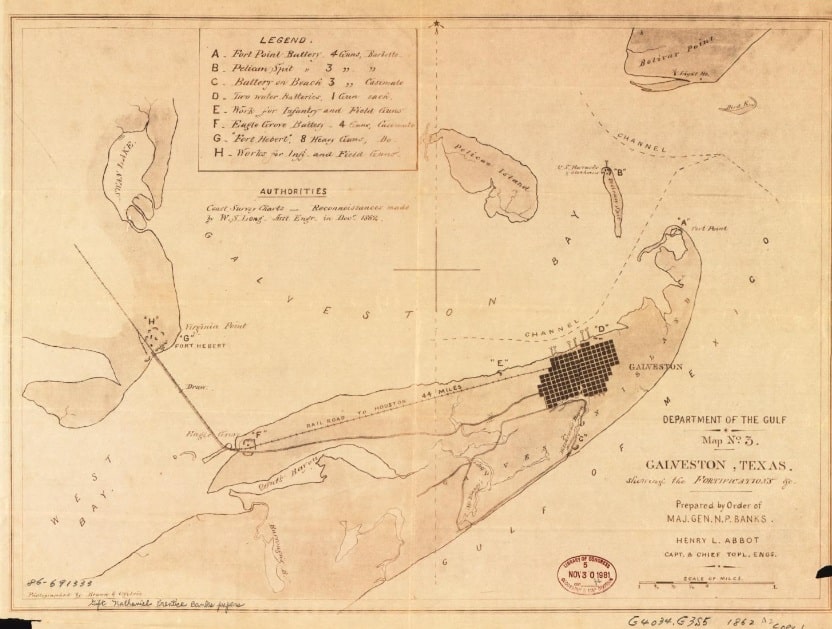

As Union forces occupied the city following its abandonment by Confederates in October 1862, Harriet Lane was largely confined to Galveston Bay, monitoring any suspicious activity by potential blockade runners. While Federal forces began their occupation of the city, Confederate leadership in the region also witnessed a change. Taking command of the District of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona was Maj. Gen. John Bankhead Magruder. Almost immediately following his arrival in Houston, Magruder began to formulate plans for a joint sea-land operation to retake Galveston. That plan came into fruition in the early morning hours of January 1, 1863.

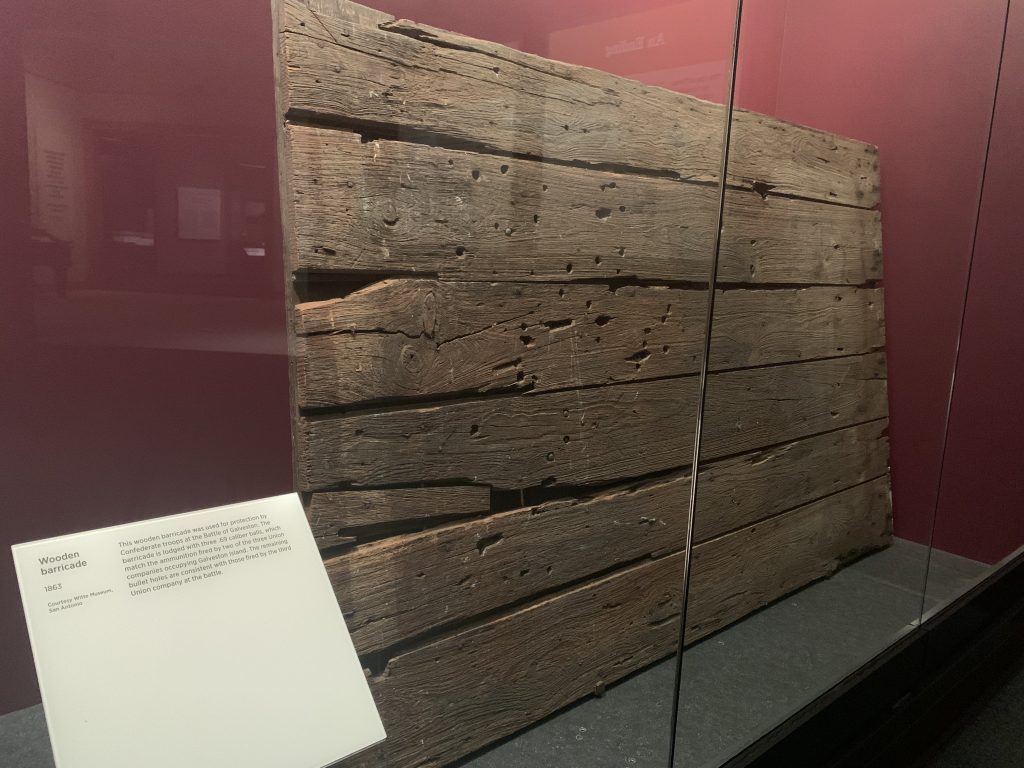

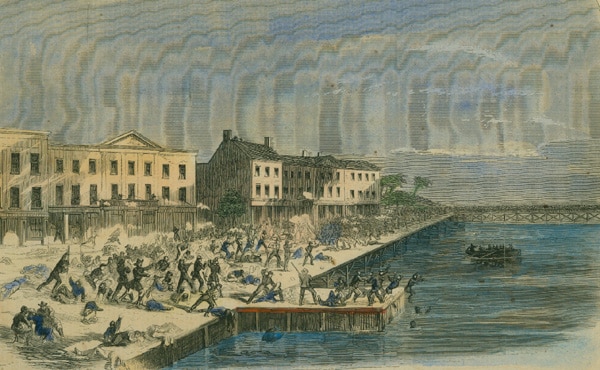

To conduct the assault on Galveston, Magruder had under his command troops who had served in Gen. Henry Sibley’s failed New Mexico expedition. Additionally, a small hastily constructed flotilla of cottonclads, under the command of Leon Smith of the Texas Maritime Department, was used in the assault to support the ground troops. When Confederate artillery fired in the vicinity of Kuhn’s Wharf–where several companies of the 42nd Massachusetts Infantry were stationed–the cottonclad flotilla did not immediately appear.

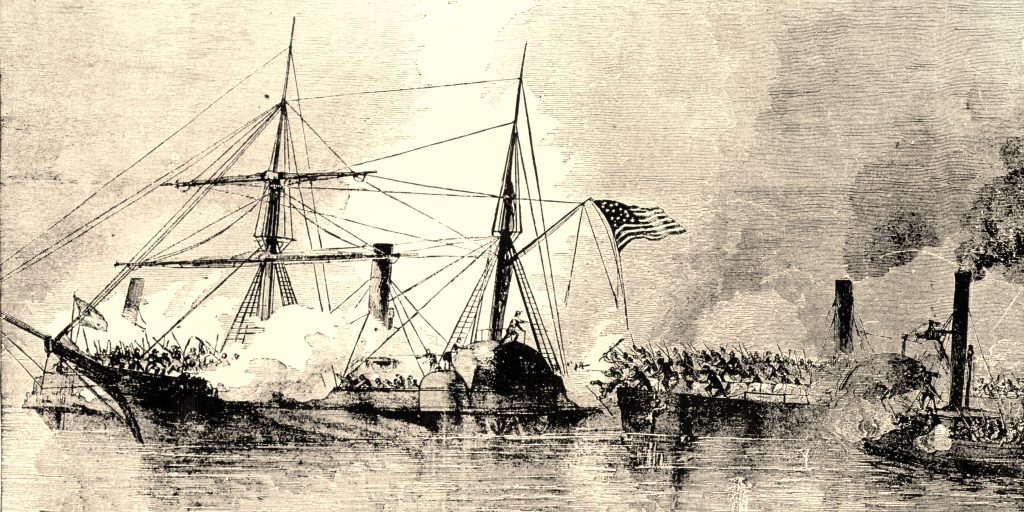

During this portion of the battle, Harriet Lane and several other vessels provided crucial naval firepower for the Federal infantry. Magruder’s forces desperately needed support, and for a moment it appeared that his plan would fail. However, after initial confusion, Leon Smith and his flotilla headed straight towards the Federal ships. Harriet Lane easily outgunned the two cottonclads that approached her, Bayou City and Neptune, however, due to small arms fire coming from both cottonclads, the gun crews aboard Lane were forced to go below deck to seek cover. Eventually, Lane was rammed and boarded by Confederate forces.

As Leon Smith and his troops under his command—which according to participate Robert Franklin consisted of a combination of artillerymen, infantry, and cavalry instead of Confederate sailors—began to pour onto the deck of Harriet Lane, they found that their small arms fire had killed its captain, Lt. Cmdr. Wainwright, and mortally wounded his second in command, Edward Lea.[6] According to Robert Franklin, who was a part of Bayou City’s boarding party, Lea had been “wounded in the abdomen and sides [with] 5 wounds in all.”[7]

Remarkably, shortly after the Confederates had captured Lane, Edward’s father Albert also rushed aboard. During the days preceding the battle, Albert Lea–a major in the Confederate artillery–had paid a visit to Magruder–his old West Point classmate–and served as an aide during the engagement.

Prior to the battle, the elder Lea heard a rumor that his son was serving aboard Lane. Once the fighting began to die down, Lea quickly boarded Lane and found his son dying. While he had been harsh in his rhetoric towards his son when he found out that he would not join the Confederate cause, the elder Lea quickly embraced his son. According to one account Lea “reached the scene in time to clasp his son in his arms.”[8] Lea recounted years later that he sought permission for an ambulance from Magruder, who promptly allowed him. However, by the time he returned to his son, the naval officer had already passed. As Albert Lea remembered, the surgeon who was with his son at the end remarked that his dying words were “my father is here.”[9]

The following day, Albert Lea laid to rest his son and his captain, Jonathan Wainwright. At the request of the Houston Tri-Weekly Telegraph, Lea wrote his recollections of the funeral just a few weeks after the battle. In this recollection, he spoke little of his son’s final moments, but rather of the magnitude of the occasion.

Having been granted permission, several officers from Harriet Lane served as pallbearers for the funeral. With this unique show of mourning, Lea wrote that “the national hate, engendered by the war, and especially excited by the recent contest, had shown itself partially in personal aversion to the unfortunate prisoners” as men both North and South mourned the loss of Lt. Cmdr. Edward Lea.[10]

Edward Lea was laid to rest in the Trinity Episcopal Church Cemetery in Galveston. While his commander’s body was later exhumed and relocated to Annapolis, Edward’s father refused to have his son exhumed as he believed he would have wanted to remain on the field where he had died. For the elderly Lea, this grave was a fitting place for his son as it was “in sight of the sea, in sound of the surf, where such devoted sailors would love to lie.”[11]

Long beyond his death, the story of the Leas continues to capture the interests of the Civil War community. For historians like Edward Cotham, this was one of the most “heart-stirring stor[ies] in the whole Civil War.”[12] Stories such as this demonstrate to us that the Civil War was a conflict that impacted individuals on a personal level. While the battle of Galveston is often forgotten in the grand scheme of the conflict, families like the Leas would not forget that terrible day when a father saw his son die opposing him in a civil war.

Riley Sullivan earned his MA in History at Sam Houston State University and is a Professor of History at San Jacinto College in Pasadena, TX. He has published works on Civil War Memory that have appeared in the Tennessee Historical Quarterly. He is also a doctoral student in the Department of History at the University of Houston.

Endnotes:

[1] Dorman H. Winfrey, “Two Battle of Galveston Letters,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 65, no. 2, (Oct. 1961); 252.

[2] Porter wrote this in his memoirs as he recalled his relationship with Edward Lea (referring him to Lieutenant Lee). However, this is an interesting statement as Maryland was a Southern state that remained loyal to the Union. David Dixon Porter, Incidents and Anecdotes of the Civil War, (D. Appleton and Company, 1885), 110.

[3] While Albert M. Lea was not a well-known frontiersman, Albert Lea, Minnesota is named in his honor.

[4] Porter, Incidents and Anecdotes, 111.

[5] Edward Lea to Gideon Welles, 28 December 1861, Navy Officer’s Letters 1802-1884, The National Archives, Washington D.C., Fold3, https://www.fold3.com/image/638402628/lea-edward-page-1-us-navy-officers-letters-1802-1884?terms=lea,war,us,edward,civil,union,united,america,states,lea,%20edward (accessed July 30, 2025).

[6] Franklin, Robert M. Battle of Galveston, January 1st. (Galveston, Tex., The Galveston News, 1911) Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/39020660/. 2.

[7] Ibid, 11.

[8] Edward B. Williams, “A ‘Spirited Account’ of the Battle of Galveston, January 1, 1863,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 99, no. 2, (Oct. 1995); 213.

[9] Freeborn County Standard (Albert Lea, Minnesota), May 15th, 1890.

[10] Tri-Weekly Telegram, (Houston, TX), February 27th, 1863.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Edward J. Cotham, Battle on the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston, (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1998): 136.

Thanks for this touching, heartfelt narrative!

Wow. It doesn’t get any more personal than that. Thanks

This is a wonderful story. We forget how personal this war (and all wars) could be.

A compelling story. Thanks for sharing it.

Wainwright’s grandson commanded US troops in the Philippines in 1942.

Excellent, thought producing story