Rebel Tracks: Following Confederate P.O.W. James E. Ankers

Northern Virginia was torn apart during the Civil War, both physically and ideologically. An agricultural landscape that witnessed enormous battles, mass army movements, and the construction of dozens of forts, many families were displaced or shattered by the conflict. Some residents in this part of the state embraced the Southern cause, even if their families did not benefit from the horrid institution of slavery. The following is an account of Confederate Pvt. James E. Ankers, a Loudon County man whose confinement in four prisons across the Union culminated in personal defeat and familial upheaval.

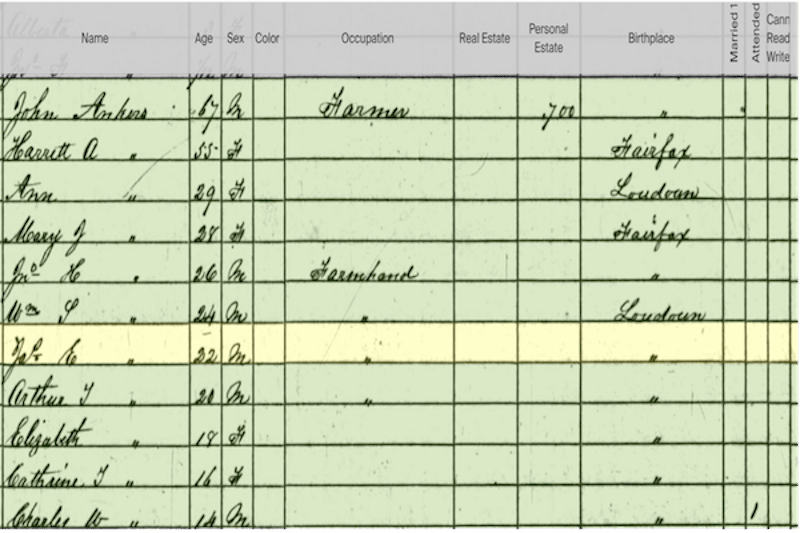

James Edwin Ankers was born in November 1837 at Guilford Station, now the modern town of Sterling. This region remained primarily farmland until the mid-20th century, during suburban Washington’s mass development. The fifth child and third son of John Ankers and Harriet Hess, he and his nine siblings worked on the family farm and received a basic education – although James opted to omit his signature within his Confederate service record.

John Ankers, a War of 1812 veteran who enlisted in the summer of 1814[1], was a second-generation Northern Virginian (his own father moved the family from Maryland). The Ankers’ farm relied on enslaved labor. According to the 1830 Slave Schedule, John held four people in bondage: one man, one woman, and their two inferred children.[2] While the Ankers were not as wealthy as the nearby Fairfax and Lee families, this ownership – along with supporting nine children to adulthood – showed they maintained some wealth either through revenue or generational inheritance. However, their status in Loudon County diminished greatly when the war concluded in 1865.

The Ankers were prominent and numerous in this part of Loudon County. James’s parents remained at Guilford Station as the war raged on. Relatives owned a blacksmith shop in the vicinity, which became entangled in one of Mosby’s raids, later known as the “Ambush at Ankers’s Shop.”[3] While we may never know the true motivations behind the Ankers’s support of the Confederacy, it is clear that their historic use of enslaved labor and self-identification as Virginians led them to favor secession. Unlike other secessionists in the region, they did not abandon their property to flee further into “Dixie.”

On October 1, 1862, James enlisted in Company K of the 6th Virginia Cavalry (the Loudon or Leesburg Cavalry) in the nearby town of Snickersville (now Bluemont). He followed in the footsteps of his older brother Samuel, who joined the 38th Battalion in June 1861, one week after Virginia seceded from the Union. After suffering slight wounding at Upperville and witnessing Gettysburg, James Ankers blasted through the beginning of the Overland Campaign, surviving Wilderness and Spotsylvania Courthouse.[4]

n January 1864, older brother Samuel was removed from the front lines and reassigned to “detail” at General Hospital No.9 in Richmond. Also called “Seabrook’s Hospital” or “Receiving and Wayside,” it held over 1,500 patients when Samuel arrived on January 12, even though the capacity was capped at 900.[5]

Of the four Anker sons eligible to enlist in the Civil War, only two did. Eldest brother and third child John (b.1834) and sixth child Arthur (b.1840) have no record of enlistment or service for either the Union or Confederacy. Samuel thus had a heightened awareness of James’s fate and likely kept closer tabs on him from the Richmond hospital. Did Samuel await his younger brother’s admission for illness or injury? How many 27-year-old Virginian soldiers were brought in on stretchers or in literal pieces that reminded Samuel of James?

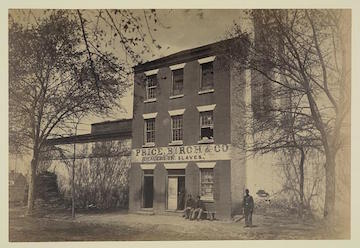

As luck would have it, James’s initial wave of success and survival came to a crashing halt when he was captured at Cold Harbor on May 31, 1864. By June 5, he was confined to Point Lookout in Maryland, where he remained until January 8, 1865. For reasons unknown, Ankers was removed from this bay-side prison during that harsh winter month and transferred to the Union-occupied town of Alexandria. It is likely that he was in the running for prisoner-exchange, and Alexandria was often utilized to keep P.O.Ws close to the border – but that system had come to a sudden interruption. James’s chances of exchange were slim. After one month of confinement in the Franklin and Armfield slave auction house, confiscated as the damp and dark “Slave Pen Jail,” he contracted pneumonia. Union officials kept rebel soldiers and civilian secessionists in the same cells that once detained enslaved persons before sale, holding a symbolic meaning against the Confederate cause.

Ankers was admitted to Grosvenor Branch Hospital on February 9, which still stands as the Lee-Fendall House Museum. For three weeks, he received treatment and care from Head Surgeon Maj. Edwin Bentley and the assistant surgeons until his return to prison on March 2. This hospital held a capacity of 150 beds, but often more patients than that. The first floor, where Ankers was possibly chained to his cot or kept under watch, was mandated for private rank, while the second floor was reserved for officers’ quarters and the third for staff housing. He was among a large wave of prisoners, both Union and Confederate, that were treated at Grosvenor Branch due to the horrid conditions in Alexandria’s five military prisons. Ankers was one of three rebel prisoners-of-war assigned to this hospital for medical care.

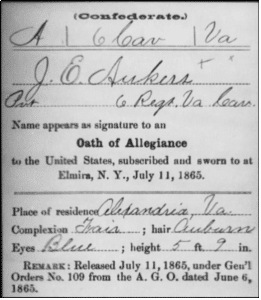

Upon returning to the Slave Pen, he remained incarcerated for a few more days until his removal to the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C., currently the site of the Supreme Court building. Ankers spent twenty days in the District’s largest correctional facility before one last transfer to his final imprisonment: Elmira. He endured two days of travel to New York by rail lines and bumpy wagon rides. Insight into Ankers’s time at the Elmira prison camp lie in the military records at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., however, much can be assumed about his four months in the “Andersonville of the North.” Ankers was not released until General Orders 109, which authorized the discharge of rebel prisoners upon taking the oath of allegiance.

Over a month after President Andrew Johnson issued the order, Ankers pledged his loyalty once again to the United States, thus certifying his release from Elmira and his ability to go home to Loudon County and see father John before the patriarch’s death in 1867. In the 1870 census, James is living at home with his mother Harriet (now 65) and four siblings. Samuel, John, Jr., and little sister Catherine, each married and moved away.

Arthur retuned to the household in 1880, listed as its head, right before their mother passed away. The Ankers’ farm was valued at $300 at the time of the 1870 census, and two sons experienced unemployment in the aftermath of the war. The region itself was shattered by fraternal loss and scorched earth, scattering starving families out of the county. James labored at the nearby Colvin Run mill to support his extended family. Did he speak of his imprisonment in four Union cells? Did the pneumonia still haunt him as he toiled at the mill?

In 1895, at the age of 58, James married Sarah Lloyd. This was his first and only marriage. The couple did not have any children. Their marriage was short-lived, as James died in 1909 and Sarah in 1915. Both of their tombstones at the Old Sterling Cemetery are simple and do not note James’s Confederate service.

Despite their financial hardships and parental deaths, none of the Ankers children moved out of Loudon County. Their struggles on the farm led a descendant, somewhere on the family tree, to relinquish the property. Guilford Station is no longer. Now the name of a shopping mall on the site of the Ankers’ post office, it sits just six miles from Dulles International Airport. All evidence of the Ankers’ once prosperous farm – and their Confederate cause – lie under the busy Route 28 in Sterling, Virginia.

Endnotes

[1] Ancestry.com, U.S., War of 1812 Pension Application Files Index, 1812-1815 from National Archives, Index to War of 1812 Pension Application Files, 1960 – 1960, Records of the Department of Veteran Affairs, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/563315.

[2] Ancestry.com, 1830 U.S. Federal Census from National Archives, Fifth Census of the United States, 1830, Records of the Bureau of the Census, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8058/records/860950?tid=105742216&pid=160047333568&ssrc=pt

[3] Craig Swain, “Ambush at Ankers’s Shop,” Historical Marker Database (2022), https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=42329

[4] Fold3, “Ankers, James E.,” US, Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Virginia, 1861-1865, https://www.fold3.com/file/7948016.

[5] Civil War Richmond, “Statistics of General Hospital #9,” https://www.civilwarrichmond.com/images/pdf/stats_gen9.pdf.

Biography

Madeline Feierstein is an Alexandria, VA historian specializing in psychiatric institutions, hospitals, and prisons. A native of Washington, D.C., her work has been showcased across the Capital Region. Madeline leads efforts to document the sick, injured, and imprisoned soldiers that passed through Civil War Alexandria. Additionally, she interprets the burials in Alexandria’s historically rich cemeteries with Gravestone Stories. Madeline holds a Bachelor of Science in Criminology from George Mason University and a Master’s in American History from Southern New Hampshire University. Explore her research at www.madelinefeierstein.com.

Good story. And how that war changed (and is still changing) everything.

A poignant story , extremely well written. A fine addition to the many ECW articles.

An interesting, sad story