The Making of a Riot: Political Violence in Civil War Illinois

ECW welcomes back guest author M.A. Kleen.

In late March 1864, members of the 54th Illinois Infantry Regiment gathered around a small-town courthouse, waiting to board a train back to their unit, when an argument with resentful civilians erupted into gunfire. The clash, which left nine dead and twelve wounded, occurred not in the South, but in Charleston, Illinois.

Known as the Charleston Riot, it was the deadliest episode of Northern home-front violence outside the New York City Draft Riots and drew national attention when President Abraham Lincoln personally intervened. Pitting antiwar Democrats against hometown soldiers on furlough, the incident raised a pressing question: how could such bloodshed happen so far from the frontlines?

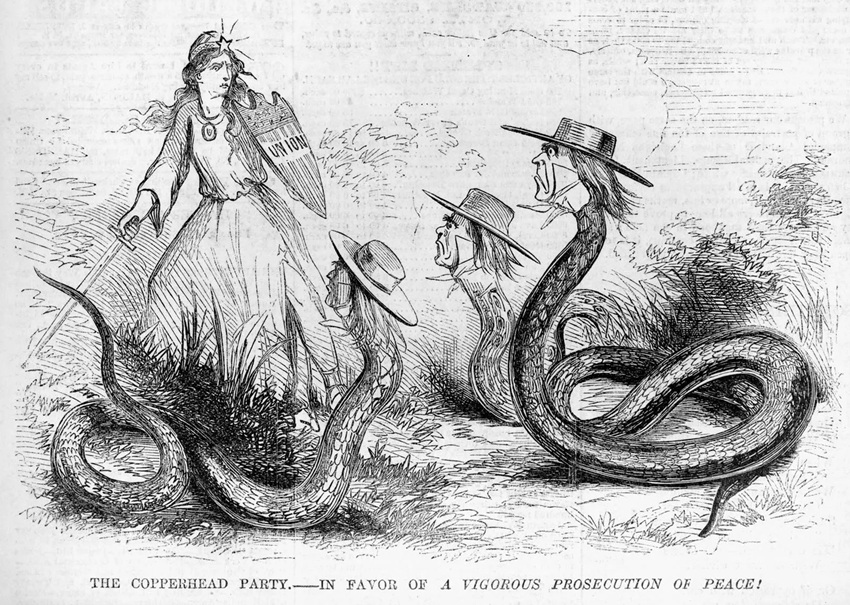

By 1864, mounting casualties fueled Northern opposition to the Civil War, and Democrats sought to harness this discontent without stoking Republican suspicions of disloyalty. This balancing act split the party into War Democrats and Peace Democrats, the latter derisively nicknamed “Copperheads,” a label some embraced by wearing copper Liberty Head coins.

Historians have long debated the roots of Copperheadism’s appeal.[1] My own research suggests that, at least in Illinois, Copperheadism had more to do with longstanding political rivalries than with economic and cultural ties to the South. Southern Illinois shifted heavily toward unionism as the war progressed, despite the region’s overwhelming Democratic vote in the 1860 election. Central Illinois, where the margin between Republicans and Democrats was razor-thin, became the hotbed of Copperhead activity.[2]

Several academic articles examining events surrounding the Charleston Riot have been published in Illinois state historical journals, but despite its importance to Copperheadism’s broader story, the riot has never received the national attention it deserves.

The story of the riot is the story of escalating political tensions in east-central Illinois during 1863 and early 1864. Although Abraham Lincoln won Illinois in the 1860 presidential election, opposition to the Emancipation Proclamation and the suspension of habeas corpus handed Democrats a majority in the state legislature during the November 1862 midterm elections. Passage of the nation’s first conscription law in 1863 further inflamed tensions, and Illinois Democrats attempted to pass resolutions and legislation calling for an armistice, restricting use of the state militia, and obstructing the draft.[3]

Republicans responded by accusing the Democratic Party of disloyalty, even treason. In February 1863, State Senator Isaac Funk delivered a widely published speech, saying, “…the country would be the better of swinging them up… What man, with the heart of a patriot, could stand this treason any longer?”[4] In June 1863, Illinois’s Republican Governor Richard Yates exploited a loophole in state law that allowed him to decide how long the legislature would remain in recess if the House and Senate did not agree on a recess date. He prorogued them for two years and ran the state as its de facto dictator.[5]

The political situation deteriorated further with the military arrest of Charles H. Constable, judge of the Illinois 4th Circuit Court. In March 1863, Judge Constable ordered the release of Union Army deserters who had been arrested by Union soldiers in east-central Illinois. The Clark County sheriff then arrested the two sergeants leading the posse on kidnapping charges. In response, Col. Henry B. Carrington led a force of over 200 Union soldiers to Marshall, Illinois, to arrest Constable at the county courthouse as he presided over the sergeants’ trial. They ultimately turned him over to federal court, where the charges were dismissed.[6]

Constable became a cause célèbre among Peace Democrats and a target of derision among Unionists. On January 29, 1864, soldiers on leave in Mattoon, Charleston’s sister city in Coles County, forced Constable to kneel in the mud and swear a loyalty oath. The next day, Charles Shoalmax of the 17th Illinois Cavalry shot and killed a man named Edwards Stevens who tried to escape the same fate.[7]

In February, trouble between Union soldiers on furlough and local Copperheads again boiled over, this time in Edgar County, east of Coles County. There, in the town of Paris, Amos Green, a member of the Order of the American Knights, operated a Democratic newspaper. At a Democratic meeting in Mattoon in August 1863, he reportedly told the crowd, “They would appeal to the ballot-box for their rights, and if they could not get them in that way, they would appeal to the cartridge box.” Members of the 12th and 66th Illinois infantry regiments forced Green to swear an oath and pledge a sum of money to prove his loyalty to the Union.[8]

In a confrontation in the streets of Paris, a soldier named John Milton York shot and seriously wounded an outspoken Copperhead named Cooper. Edgar County Sheriff William S. O’Hair attempted to arrest the soldier, but one of York’s compatriots prevented him from doing so at gunpoint. York was eventually arrested, but the court released him on a technicality and he rejoined his regiment.[9]

On hearing rumors that the soldiers planned to burn the newspaper office before returning to the front, Sheriff O’Hair, accompanied by over a dozen men, rode into town on the day the furloughed soldiers were to leave. Someone informed the soldiers of the posse’s whereabouts, and they immediately went to investigate. As they approached an alley, a group of men fired on them before fleeing toward a horse stable on the edge of town, where Sheriff O’Hair and his posse were presumably waiting. These men then promptly escaped.

As the soldiers approached the stable, Alfred Kennedy, a young man hiding inside, shot one of them in the wrist. Private Mark Boatman of the 12th Illinois peered into the building as he heard Kennedy call out that he surrendered. As Boatman lowered his weapon, Kennedy shot him in the shoulder. More Union soldiers arrived and poured a volley into the stable, riddling the planks with bullets. When they looked inside, they found Kennedy badly wounded. Kennedy told the soldiers that his fellow Copperheads had planned to ambush them at the train station.[10]

Some participants in the Charleston Riot had familial ties to the participants in the February Edgar County affair. John Henry O’Hair, sheriff of Coles County, was William S. O’Hair’s cousin. Both were known for their Copperhead leanings. Major Shubal York, surgeon of the 54th Illinois, was from Paris and was the father of John Milton York. These family connections meant that the violence in Edgar County had personal implications for key figures at the Coles County Courthouse that fateful Monday, March 28, 1864.

The Charleston Riot emerged not from spontaneous wartime tensions, but from a sequence of political provocations, personal vendettas, and escalating confrontations across east-central Illinois. What began as ideological disagreements over emancipation and federal authority had devolved into a bitter cycle of retribution. By March 1864, conditions were ripe for violence. The deadly riot that followed was the culmination of months of political warfare that had transformed ordinary citizens into enemies and reduced democratic debate to the language of bullets.

M.A. Kleen is a program analyst and editor of spirit61.info, a digital encyclopedia of early Civil War Virginia. His article “‘A Kind of Dreamland’: Upshur County, WV at the Dawn of Civil War” was published in the Spring 2025 issue of Ohio Valley History.

Endnotes:

[1] See: Jennifer L. Weber, Copperheads: The Rise and Fall of Lincoln’s Opponents in the North (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006); Frank L. Klement, “Midwestern Opposition to Lincoln’s Emancipation Policy,” The Journal of Negro History 49 (July 1964).

[2] Michael Kleen, “The Copperhead Threat in Illinois: Peace Democrats, Loyalty Leagues, and the Charleston Riot of 1864,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 105 (Spring 2012): 69-92.

[3] Willard L. King, “Lincoln and the Illinois Copperheads,” Lincoln Herald 80 (Fall 1978): 134-135; James J. Barnes and Patience P. Barnes, “Was Illinois Governor Richard Yates Intimidated by the Copperheads During the Civil War?,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 107 (Fall/Winter 2014): 338-339.

[4] Loyal Publication Society, The Three Voices: Soldier, Farmer, and Poet. To the Copper Heads (New York: Rebellion Record), 1-2.

[5] John H. Krenkel, ed., Richard Yates: Civil War Governor by Richard Yates and Catharine Yates Pickering (Danville: The Interstate Printers & Publishers, 1966), 182-184.

[6] Stephen E. Towne, “‘Such conduct must be put down’: The Military Arrest of Judge Charles H. Constable during the Civil War,” Journal of Illinois History 9 (Spring 2006): 43-62.

[7] Sampson, 111; Charles H. Coleman and Paul H. Spence, “The Charleston Riot, March 28, 1864,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 33 (March 1940), 16.

[8] Peter J. Barry, “Amos Green, Paris, Illinois: Civil War Lawyer, Editorialist, and Copperhead,” Journal of Illinois History 11 (Spring 2008): 48-49.

[9] Independent Gazette (Mattoon), 7 February 1864; Richard K. Tibbals, “‘There has been a serious disturbance at Charleston…’: The 54th Illinois vs. the Copperheads,” Military Images 21 (July-August 1999), 11.

[10] Crawford County Argus (Robinson), 10 March 1864; John Scott Parkinson, “Bloody Spring: The Charleston, Illinois Riot and Copperhead Violence During the American Civil War” (Ph.D. diss., Miami University, 1998), 168-71.

With the eruption of war at Fort Sumter, the situation “became real” for Illinois – a long, shield-shaped state that even today requires four hours to drive from extreme south to the northern boundary with Wisconsin. Within that State, Chicago and Springfield and Rock Island in 1861 were Union as Union could be; but as one progressed south from Springfield, the character of the residents became decidedly pro-Southern in sentiment. Cairo, a river port at the far southern extremity of Illinois, is further south than St. Louis; further south than Louisville, Kentucky; and Cairo is even further south than Richmond, Virginia.

The families established in Southern Illinois often traced their ancestry back to Kentucky and Virginia; and it is this researcher’s belief that “there are few things stronger than family ties.” Even though the leaders of Southern Illinois – most famously Members of the U.S. House of Representatives John McClernand and John A. Logan – soon joined hands with President Lincoln in efforts to put down the rebellion, many families “represented” by McClernand and Logan, did not. These families decided to “sit out the war,” or in some cases their sons went south. No real impact was felt until the volunteers from Illinois were all signed up, and the Lincoln Administration implemented the draft.

Suddenly “sons with Southern ancestry” were being called upon to fight other “sons of Southern ancestry.” Also, with the release of President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation on 1 January 1863, the War of the Rebellion suddenly appeared to have become “The Fight Against Slavery.” This was too much of a leap for some Illinois families, with some (already involved in the Copperhead “peace” movement) taking the next step and joining the Knights of the Golden Circle – called the Order of American Knights in the Northern states. Until conclusion of the war, efforts were made to use KGC and their fellow travellers as “Fifth Column” operatives, sabotaging the Northern war effort; but these efforts were mostly without success. Even the Riot at Charleston – scene of one of the seven Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858 – was more a case of “local citizens who felt they had been put-upon enough, already” …that boiled over… than any Fifth Column activity.

Thanks to M.A. Kleen for revealing that “the South was not a monolith” and “the North was not a monolith” during the Civil War. Pockets, and sometimes WHOLE counties full of disaffected citizens could be found on either side of the Mason-Dixon Line.

For further reading about “Little Egypt, Illinois” see: https://www.mihp.org/2015/08/the-illinois-confederates/ and

https://brittlebooks.library.illinois.edu/brittlebooks_closed/Books2009-04/daytar0001reccon/daytar0001reccon.pdf

Very interesting articles! A couple of things though – it is definitely more than a four hour drive the entire length of Illinois, more like seven. I grew up in the NW Chicago suburbs and my sister went to SIU-C. It’s true that, at the very onset of the war, many in southern Illinois supported the Confederacy and some counties even passed their own secession referendums. But before he died, Steven Douglas went to southern Illinois and convinced many to support the Union. Southern Illinois became a banner recruiting area for the Union Army and they voted for Lincoln in large numbers in 1864.

Michael Kleen

Although I am reasonably certain you have noticed this article before, I will post this for interested ECW readers: The Storm is On Us by Jeremy R. Knoll (2021) https://huskiecommons.lib.niu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=studentengagement-honorscapstones

It contains a concise summary of Chicago’s pre-Civil War preparations for “the coming storm.” Mention of the Chicago Wide Awakes, Elmer Ellsworth’s Zouaves and arguably the most important unsung hero of the Civil War: Richard Kellogg Swift, Brigadier General of Chicago Militias. Working in cooperation with Governor Richard Yates, Swift accompanied 400 militiamen and numerous cannon south, riding the rails of the Illinois Central to its terminus at Cairo, not knowing whether or not the rumours of “Southern designs on that important river port” were true; but forced to respond to claims of “sabotage of key bridges” as if they were true. By the end of the day, 22 April 1862, Cairo [which would become the major port for the Western Gunboat Flotilla] was in Union hands; and for the remainder of the war, Cairo would never be seriously threatened.

All the best

Mike Maxwell

Of course the date of Brigadier general Swift’s arrival at Cairo Illinois should read “22 April 1861” – my clumsy error making it read otherwise. But as I pondered how best to correct the error in the above post, I recollected the MANY events that took place immediately after the “shots igniting Civil War were fired at Fort Sumter.” 1) Fort Pickens at Pensacola Bay was reinforced; 2) Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and New York mobilized troops to speed south and defend the Capital of Washington D.C.; 3) New York City disengaged from consideration of “creating a CSA-friendly Free City of Tri-insula;” 4) President Lincoln called for troops; 5) Virginia withdrew from the Union; 6) Cairo (a strategically necessary “base of operations” for conducting waterborne missions) was secured for the Union.

There are probably many more noteworthy events that took place within ten days of the Fort Sumter event; but these are the ones that immediately presented to my recall.