Finding Clara Barton at her Washington, D.C. Home

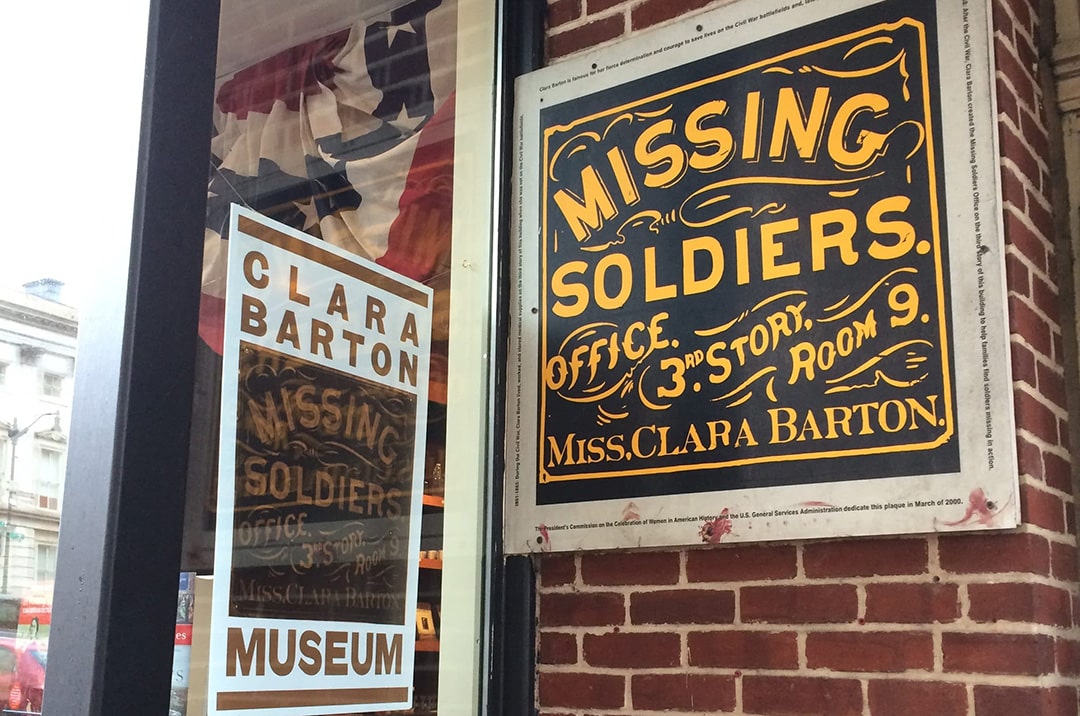

It is an extraordinary task to rebuild a person’s life within a blank space and tell their story. How can we transform an empty room, where immense necessity and urgency once occurred, and reimagine it as the site it once was? At the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office in Washington, D.C., this otherwise tedious task became the motivation when the museum opened in 2015. Since then, its mission has been twofold: to experience Clara Barton’s Washington world and to grasp the harsh reality of going missing during the Civil War. As an extension of the work curated at National Museum of Civil War Medicine, Site Administrator Madeleine Thompson reveals that this boarded-up boarding house is where Clara Barton’s story truly begins.

The tale of this miraculous discovery has been widely-storied. Upon leaving the boarding house in 1868, Clara Barton’s life in Washington – along with her Missing Soldiers Office (MSO) – was packed away and stored in the attic above her bedroom. Edward Shaw, the landlord who offered his several boarding rooms to serve as the MSO, wanted to keep these important artifacts and documents in a safe space. The entire third floor had been boarded-up in the 1910s in response to changing fire codes, trapping these historical items in Shaw’s hiding place for over 120 years.

Interpreting this history is no small task. As Site Administrator, Madeleine Thompson’s responsibilities range from daily operations to developing programming to training docents. She assists in envisioning Barton’s life while the Civil War nurse resided here, which she views as a continuation of her dissertation on interpreting women’s living spaces. “The actions Barton takes while living at 437 7th Street (in her time, 488 1/2 7th Street) set her on the path to becoming a national icon,” Thompson notes, “What begins to set her apart is her persistence and unwillingness to comply with expectations of the society she lived in. As a single woman, she secured permission to work on the front lines – something virtually unheard of at the time. But her most unprecedented work came after the war ended. The Civil War itself was unprecedented in its casualties and the sheer number of missing soldiers it left behind. Clara recognized this urgent need and mobilized again, but now with a different mission.”

The MSO is quite critical to understanding the social implications of a civil war on a nation. We read casualty reports and notice the regular labeling of soldiers as “missing.” But what does that truly mean for that individual, their regiment, that battle, and for their families waiting at home? This is where the establishment of the MSO in 1865 truly matters. “The MSO work profoundly transforms Clara’s sense of purpose,” Thompson asserts, “and breathing life back into the site has been a project in itself.” The museum offers guided tours twice a day during its operating hours, with a tour script that not only touches on Barton’s humanitarian work on the battlefield, but also her extraordinary accomplishment: identifying the whereabouts of 22,000 missing men. “She brought closure to these families – if you can imagine it, all without cell phones, emails, or even dog tags to identify the deceased.”

A team of 21 aides assisted Barton with this monumental task, moving away from the “conventional wartime support” that she had been providing for the duration of the war. “If she stopped there,” Thompson explains, “the museum would likely not be preserved. Luckily, she didn’t!” In the same rooms that Shaw dedicated to the MSO, visitors can now attend lectures and interpretive programs organized by Thompson and the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. Other rooms detail Barton’s transformation from federal worker to battlefield nurse to humanitarian innovator. Several spaces display artifacts from moments that profoundly changed her life, such as her visits to the heinous Andersonville prison and bloodied socks that she had sewn for Union troops.

Clara Barton’s life story, as told through these boarding rooms, is one that many of us can relate to. “What’s most poignant about Clara’s journey to me is that she spent much of her life doubting herself. It wasn’t until she found her place during the Civil War that she discovered her life’s purpose – and that transformation happened in this building.” Thompson points out. “We get to explore what daily life looked like for an unmarried, middle-class working woman living in a modest boarding house – complete with all the social constraints and personal struggles that entailed. While we certainly discuss military strategy on occasion, our primary focus is on everyday life and how one woman’s determination could reshape her world and, ultimately, the nation’s approach to its wounded and missing.”

When I personally wander around the corridors and hop over a threshold, I feel that I’m glimpsing into a time far removed from my own. While some of these rooms are temporarily empty, it does not feel as though the space itself is void of energy and memories. Thompson refers to this experience as being surrounded by tangible evidence of Clara’s presence. The 1853 floors are well preserved, her original chosen wallpaper is still on display, and many original doors and windows remain intact. The MSO is a genuine time capsule, she told me, one that is “distinctly unlike most Civil War sites I’ve visited.”

So, what’s next for the Missing Soldiers Office? The MSO is fortunate to not require any major renovations or stabilization due to the effective preservation efforts prior to the museum’s opening in 2015. Thompson works diligently to secure thrilling lectures and interesting talks throughout the year – although I am biased since I’m one of these upcoming lecturers! “We are exploring how interpretation and staging can better reflect Clara’s daily life and the site’s historical significance and will continue to update how we present the site. We are simultaneously redesigning our sister site, the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, so I am overjoyed that our sites will be evolving alongside each other!”

————

Madeleine Thompson is the Site Administrator of the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum, part of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, in Washington, D.C. She holds a Master of Arts in Sexual Dissidence from the University of Sussex in Brighton, England, where her dissertation examined themes of feminine resistance, religion, and medical practices within the medieval bedroom. Madeleine earned her Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from West Virginia University, with minors in History and Women’s and Gender Studies. Prior to joining the Museum, she worked as a talent acquisition specialist at a biopharmaceutical company. Though she has familiarity with modern healthcare, her passion has always centered on history—a calling she now pursues through preserving the history of Clara Barton’s groundbreaking work at the Missing Soldiers Office.

Madeline Feierstein is an Alexandria, VA historian specializing in psychiatric institutions, hospitals, and prisons. A native of Washington, D.C., her work has been showcased across the Capital Region. Madeline leads efforts to document the sick, injured, and imprisoned soldiers that passed through Civil War Alexandria. Additionally, she supports the National Museum of Civil War Medicine and interprets the burials in Alexandria’s historically rich cemeteries with Gravestone Stories. Madeline holds a Bachelor of Science in Criminology from George Mason University and a Master’s in American History from Southern New Hampshire University. Explore her research at www.madelinefeierstein.com.

Very nice story. Adding the MSO to my bucket list.