On the Road to Atlanta: An English Poet at Peach Tree Creek

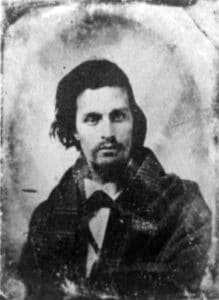

What was Richard Realf doing in Georgia on July 20, 1864?

he was 18. That work drew the attention of no less than Lady Anne Byron, the former wife of Lord Byron.

However, in the best tradition of poets, Realf was, to quote one of his admirers, a “misguided and erratic genius” who lived a “disordered life.” After an “unfortunate love affair” with one of Lady Byron’s distant relatives, he became distraught, ran up large debts, and became destitute. Finally, with Lady Byron’s help, he emigrated to New York to work as a teacher, later moving west to work as a journalist where he befriended John Brown in Kansas. The connection with Brown was natural; Realf was himself an abolitionist, as was his early patron. By 1862, while in Chicago, he enlisted in the newly recruiting 88th Illinois, eager to join the fight against slavery.[1]

He proved to be an excellent soldier. One signal moment came at Missionary Ridge, where he carried the 88th’s national colors: “The dark winding line climbed ever up and up, one regiment moving eagerly to the front. The heavy fire from the enemy’s rifle-pits belched forth, and the blue line, yet unformed, momentarily broke. The flag rose, and then suddenly fell to the ground, for the bearer had been shot. It seemed minutes, but it was not really a second of time, when clearly against the hazy autumn sky a slight, lithe figure, sword in hand, was seen to dash out from the swaying ranks. The flag was raised and swung aloft, as the soldier faced the command behind. Cheers were borne to the straining ears of appreciative generals and then the whole line swung swiftly forward to bayonet point under a terrific rifle fire. At the forefront was seen the soldier with pointing blade and waving colors leading the way. A moment more and the rifle-pits were reached. A second’s clash and the flag was there above the low line of rifle-pits. Over the works went the Eighty-eighth Illinois.” That sword-waving officer was Realf.[2]

As part of Nathan Kimball’s Brigade in John Newton’s Second Division, 4th corps, Realf and his comrades were attacked by Brig. Gen. Clement H. Stevens’s Georgia Brigade at the battle of Peach Tree Creek.

He now described the fight with that poet’s eye: “We had just commenced the erection of breastworks,” he wrote, “when all at once, extending far on our left and right the corps of Hardee was thrown upon us in assault. With muskets at a right-shoulder shift they moved in the confidence of expected triumph, hoping to find our lines unformed—but were received with such a dreadful and destructive fire that they were blown back in consternation.” The Rebels rallied and made a second assault, where, from the ranks of the 88th, Lt. Realf maintained his front row seat: “Again advancing and yet again—again—and yet again repulsed with tremendous slaughter. They kept up their frantic and futile efforts until dark, when they grew weary of this fruitless business and ceased for the night.”[3]

The two regiments comprising Stevens’s left bore the brunt of this firestorm. They were badly cut up. The 66th Georgia, which had begun the campaign at Dalton with more than 1,000 men had already been much reduced by casualties, sickness, and desertion. One source placed their strength at 480 men on July 20. Colonel Nisbet estimated that his casualties were 25% of those carried into action; and with a documented loss of 81 men killed, wounded, or missing, this would put the 66th’s engaged strength at about 320. A third figure comes from Lt. William Ross: “We went into the fight with 190 men,” he wrote, “& lost 74.” To Nisbet’s right, the 1st Georgia Confederate Infantry—so named to distinguish it from three other 1st Georgia infantry regiments in Confederate service—also suffered heavily. Colonel George A. Smith was killed. When the regimental color bearer when down, Pvt. Samuel Fields “seized the standard, but had not borne it five minutes before he, too, received a mortal stroke.” All told, the 1st Georgia Confederate suffered 91 losses here.[4]

Realf survived the war. He married his first wife just before enlisting, but abandoned her after the conflict to marry a second woman in Washington DC, in 1867. That marriage also failed, though he left before securing a divorce. After settling in Pittsburgh, where he lived for six years; he entered a common-law relationship with a third woman; which foundered when the second wife tracked him down. Eventually, he moved westward again, coming to rest in San Francisco, he committed suicide in 1878, drinking a bottle of laudanum.[5]

[1]Helen Daley, “Richard Realf, Poet and Soldier,” The Home Monthly vol. 8 (May, 1899), 10-11.

[2]Ibid.

[3]“My dear friends” July 21, 1864, Richard Realf Letters, Newberry.

[4]Cone, Last to Join the Fight, 131-134; Nisbet, Four Years, 209; “First Confederate Regiment,” Macon Telegraph, July 22, 1864; For losses, see Jenkins, Peach Tree Creek, 439-442, 450-453.

[5]Helen Daley, “Richard Realf, Poet and Soldier,” The Home Monthly vol. 8 (May, 1899), 10-11.

Typical poet, definitely ADHD, stimulated by battle, unhinged in civilian life. As usual, adored by women, who absurdly thought they could “reform” him. Make a great book.

Glad to see that someone has made use of my book! 😄

My great great grandfather was in the 1st Georgia Confederate Regiment and was mortally wounded at Peach Tree Creek, was captured and died on July 22nd. His name was William Riley Fields but was also known as Riley Fields. He had 3 other brothers that might have been serving with him at the time; Green, John M, and James T Fields. I wonder if the Samuel Fields mentioned above was a relative. Would love to see that Macon Telegraph article. Thanks for posting!

This story reminded me of one of my college professors-he taught(and published) poetry after years as an highly decorated Army Ranger. Warriors can have poetic souls.