Battle’s Thunderous Roar: “You saved the day at Sharpsburg”

ECW welcomes back guest author Jim Rosebrock.

As the saying goes, rank has its privileges, but rank also carries great responsibility. Being one of Robert E. Lee’s artillery battalion commanders on September 17, 1862, carried such responsibility.

We typically accord Major General Ambrose Powell Hill and his Light Division the credit for saving the Army of Northern Virginia from utter defeat at the Battle of Sharpsburg. Hill’s timely arrival at the southern end of the battlefield after a grueling 17-mile march from Harpers Ferry, and his immediate attack on the vulnerable flank of the Army of the Potomac’s Ninth Corps is the stuff of legend. It rightly played a significant and perhaps paramount role in halting the final attack of the Federal army on America’s bloodiest day.

However, in the long hours before Hill’s arrival, Lee’s army stared defeat fully in the face. His audacious commitment of Lafayette McLaws’ and John Walker’s divisions to the West Woods on the morning of September 17 and of Richard Anderson’s division to the Sunken Road an hour later stripped Lee’s line of virtually all infantry reserves until A.P. Hill’s arrival some six hours later. In the interim, Lee faced powerful attacks by the Second Corps which broke thru the Sunken Road line; by the Ninth Corps which captured the Lower Bridge and which was by 3:30 p.m., advancing inexorably toward Sharpsburg; and by a brigade size force of regular infantry and horse artillery from the Fifth Corps advancing steadily from the Middle Bridge toward Cemetery Hill. Porter Alexander rightly claimed, “Lee’s army was ruined, and the end of the Confederacy was in sight.”

The commanding general increasingly relied on his artillery, commanded by a number of relatively unknown field grade officers (majors, lieutenant colonels, and colonels) to move batteries and mass fire at critical points, and halt these powerful Federal attacks. Field grade officers have much greater authority than company grade lieutenants and captains to make these kinds of dispositions of the guns.

Lee benefited from a law enacted by the Confederate Congress on January 22, 1862, authorizing the appointment of additional artillery officers above the rank of captain. The law provided for one brigadier-general for every eighty guns, one colonel for every forty guns, one lieutenant-colonel for every twenty-four guns, and one major for every sixteen guns. Over the spring and summer of 1862, these newly minted field grade officers joined the Army of Northern Virginia.

Except for James Walton of the Washington Artillery, John Thompson Brown, of the 1st Virginia Artillery Regiment, and Lieutenant Colonel Allen Cutts of the 11th Georgia Light Artillery Battalion, this legislation made possible the appointment of every other Confederate field grade artillery officer, thirteen in all, who served with the Army of Northern Virginia during the Maryland Campaign. Every division but two, and all five reserve artillery battalions, had a field grade officer commanding its artillery.[1]

There was no corresponding legislation or regulation in the United States Army. The Federals’ only source were officers in the five United States regular artillery regiments (of whom over half were 60 years of age or older), or volunteer officers commissioned in the state light artillery regiments and battalions. General George B. McClellan had only two officers in these categories: Major Francis Clarke of the 5th U.S. Artillery, and Major Albert Arndt of the 1st New York Light Artillery Battalion. McClellan to some extent, got around this restriction by appointing two regular army artillery captains, William Hays and George Getty as aide-de-camps at the rank of lieutenant colonel. McClellan of course had Henry Hunt, who he rightly regarded “as the best living commander of field artillery.” Hunt and four field grade officers commanded a vast artillery force of 57 batteries and 305 guns. The Army of Northern Virginia with sixteen officers had three times as many officers. These officers had a disproportionately greater effect on the battle’s outcome than their small numbers would suggest.[2]

One of the newly minted Confederate field grade officers was Scipio Pierson. His background prior to the Civil War is unclear but one of his battery commanders, Lieutenant John Tullis, recalled Pierson as a French artillery officer “sent over to learn our way of fighting.” The Confederate War Department appointed Pierson a major of artillery on March 27, 1862, and assigned him as chief of artillery to General D.H. Hill. Hill who was notoriously stingy with compliments called Pierson “active, brave and efficient.”[3]

As the fighting raged at Antietam, Thomas Carter, another one of Pierson’s battery commanders recalled that he “never saw General Lee so anxious as he was at Sharpsburg.” After his abortive attack into the West Woods, Lee feared his entire left wing might be turned and ordered Carter to move to the Reel Ridge with any artillery he could collect.[4]

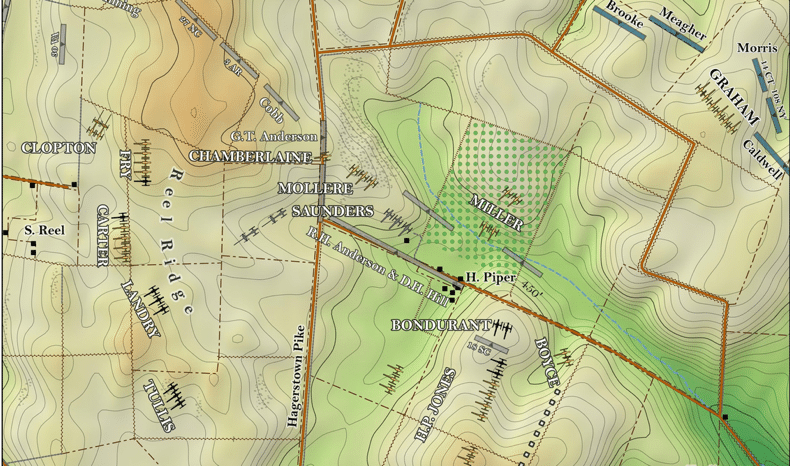

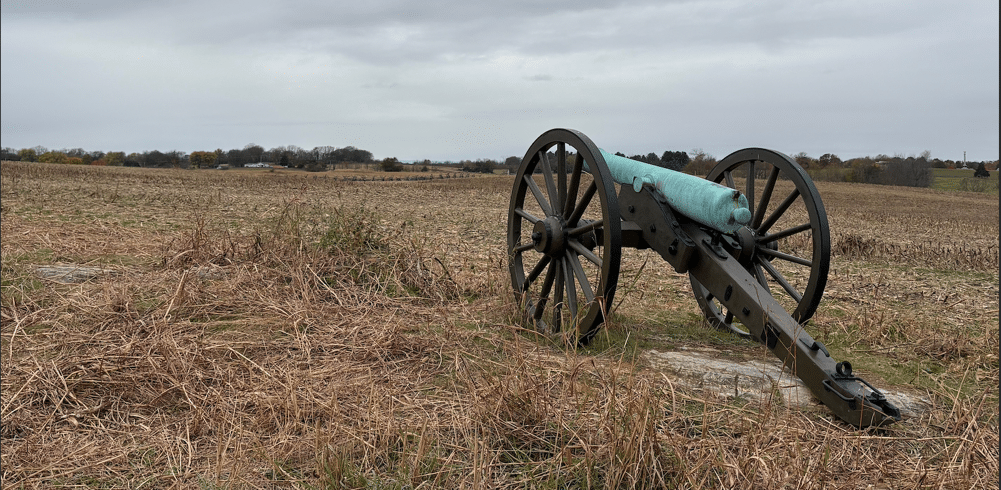

Lee’s eye for terrain was spot on. Reel Ridge is part of the series of north-south ridges that begin at Nicodemus Heights and run through Sharpsburg to the south of town along the Harpers Ferry Road. At points it is 550 feet in elevation, nearly 50 feet higher than the Hagerstown Pike to its front. Carter described this strategic position as “an eminence” where Confederate artillery could fire on any Federal advances either from the direction of “the burning house [Mumma farm buildings]” or from an enemy advance from the open field to the left of Hagerstown Pike. The ridge could accommodate four or five batteries.

Carter communicated Lee’s order to Pierson who set about assembling a total of five batteries from not only his battalion, but guns from Saunders, Cabell’s and Jones’ battalions as well. At least seven of these guns were 3-in. Ordnance or 10-lb. Parrott rifles, and one was a long-range Whitworth. All were capable of enfilading deep into French’s and Richardson’s Federal divisions advancing on the Sunken Road.[5]

Pierson’s guns were beyond the range of the Federal guns of position on the east bank of Antietam creek, and the sole Federal battery sent to support Richardson: six Napoleons from Graham’s Battery K, 1st U.S. Artillery. Graham had no trouble dealing with the rebel artillery on the Henry Piper farm but lacked the range to strike the Reel Ridge gun line. Graham’s men gamely returned fire at the distant Confederate guns for about twenty minutes, but their solid shot was falling short by “several hundred yards.” Graham advised Richardson who was standing among the guns, that he was unable to hit the enemy artillery on the Reel Ridge. The division commander ordered Graham to save his battery so it could advance with his division “at a signal then expected from General Sumner.” As he gave these orders, a spherical case ball felled Richardson.[6]

Richardson’s mortal wounding took all the starch out of the Federal attack. Thanks to the intrepid work of Pierson and his cannoneers, the Federals were unable to exploit the gaping hole torn in the Confederate line just 1,600 yards north of Sharpsburg. Scott Harwig says that, “without substantial artillery support, no advance beyond the Sunken Road could survive the fire the Rebel batteries could bring to bear on it. Offensive operations by the 1st Division [Richardson’s] were over.”[7]

Lee’s eye for terrain and Pierson’s leadership in the timely positioning of rifled artillery on the Reel Ridge prevented a Federal breakout south from the Sunken Road or west across the Hagerstown Pike. Nearly every Confederate field grade artillery officer in Lee’s army played a similar role at some point on the field in holding off the Federal attacks.[8]

Perhaps Private J.L. Napier of the Pee Dee Artillery said it best. “I always thought we were of more service to Gen. Lee’s army at this battle than at any other during the war. I believe the stand we made saved the army.” A.P. Hill simply wrote of his artillerymen, “you saved the day at Sharpsburg.”[9]

Jim Rosebrock retired from the United States Army after a 28 year career and subsequently from the Department of Justice. He has been a National Park Service volunteer, artillery reenactor, and Antietam Battlefield guide since 2007 and led the guide service from 2011 to 2018. Jim is currently the President of the Antietam Institute whose mission is to educate the public on the critical importance of the 1862 Maryland Campaign. He wrote the Artillery of Antietam in 2003 and is currently completing a companion atlas with Aaron Holley titled the Maryland Campaign Artillery Atlas due to be published early in 2026. The map in this article is taken from the upcoming atlas.

[1] The field grades appointed under the Act of January 22 1862 were colonels Henry Cabell, Stapleton Crutchfield, Stephen D. Lee, Lieutenant Colonel Reuben Walker, and majors Alfred Courtney, Bushrod Frobel, Samuel Hamilton, Hilary Jones, John Pelham, William Nelson, Scipio Pierson John Saunders, and Lindsay Shumaker. D.R. Jones’s and John Walker’s divisions were the two without field grade officers. Between them, they had just three batteries

[2] McClellan, George B. McClellan’s Own Story. William C. Prime ed. (New York: Charles L. Webster, 1887),117

[3] OR 11, pt.1, 946.

[4] John Tullis to Ezra Carman, March 19, 1900, National Archives-Antietam Studies (NA-AS); Thomas Carter to Ezra Carman, November 14, 1896, NA-AS.

[5] They included Capt. Thomas Carter’s King William Virginia Battery, and Lt. John Tullis’s Hardaway Battery. Also present was the Donaldsonville Louisiana Artillery from Maj. John Saunders’ artillery battalion of R. H. Anderson’s division commanded by Capt. Victor Maurin and Lieutenant Charles Fry’s Orange Artillery from Maj. Hilary Jones’ battalion.

[6] OR 19, pt. 1, 343.

[7] Hartwig, D. Scott, I Dread the Thought of the Place – The Battle of Antietam and the End of the Maryland Campaign (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023), 387.

[8] Rosebrock, James A., The Artillery of Antietam (Sharpsburg MD: Antietam Institute Press, 2023), 237, 252, 264, 299, 316, 333, 350,353,361, 367.

[9] Brunson, Joseph Woods, Pee Dee Light Artillery (University, AL: Confederate Publishing Company, 1983), 22; Napier to McIntosh, November 30, 1896, NA-AS.

Very interesting article…thank you!

Great post and Jims book on the Artillery at Antietam is a must have.