Warm Times in Charleston: A Civil War Riot in Lincoln’s Backyard

ECW welcomes back guest author M. A. Kleen.

In March 1864, one of the deadliest home front riots of the American Civil War erupted in an unlikely place: Charleston, Illinois, site of an 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debate and home to some of President Abraham Lincoln’s own relatives. When the smoke cleared, nine people were dead and twelve wounded, shattering the peace and tranquility of this east-central Illinois community.

The riot, an armed confrontation between Union soldiers home on furlough and antiwar Democrats known as “Copperheads,” was neither a spontaneous outburst nor a drunken brawl. It was the culmination of months of escalating political tension, inflamed to a boiling point by the pressures of civil war.

In the 1860 presidential election, Abraham Lincoln carried his home state of Illinois by a narrow margin, especially in central Illinois, where the results were razor-thin and left lingering resentment.[1] As patriotic citizens rushed to enlist, those who opposed the war stayed behind and continued to agitate against the Lincoln Administration’s domestic and military policies—what Lincoln famously called the “fire in the rear.”[2]

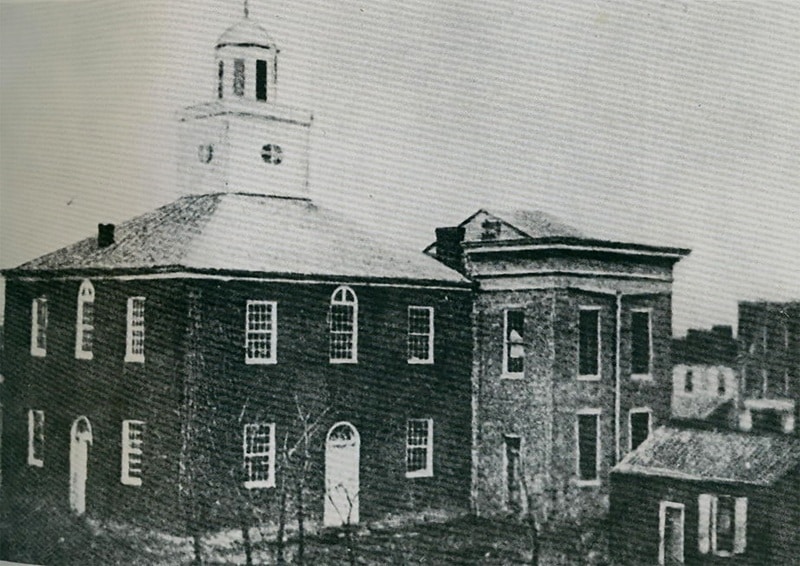

On Monday, March 28, 1864, a large crowd gathered around the Coles County Courthouse in Charleston for the opening of the circuit court’s spring session, presided over by Judge Charles H. Constable of the Illinois 4th Circuit, and to hear a speech by Democratic Congressman John Rice Eden.

The previous year, Col. Henry B. Carrington, leading a force of over 200 Union soldiers, arrested Judge Constable in Clark County while he presided over the trial of two Union soldiers accused of ‘kidnapping’ Union Army deserters. Although a federal court later dismissed the charges against him, Constable continued to face harassment from Union soldiers home on leave. In January 1864, troops on furlough in Mattoon, Charleston’s sister city in Coles County, forced him to kneel in the mud and swear a loyalty oath.[3]

Also present in the courtroom that day were Col. Greenville McNeel Mitchell, commander of the 54th Illinois Infantry Regiment, and Maj. Shubal York, the regiment’s surgeon. The 54th Illinois was composed of men from across central and southeastern Illinois, including Coles County. Many had recently re-enlisted and were home on veteran furlough. They were scheduled to assemble later that day in nearby Mattoon before returning to the front lines.

Congressman Eden nervously debated whether to cancel his speech amid the palpable tension in the air. Alcohol was being passed around freely outside among both soldiers and civilians, some of whom were armed. Eden conferred with Orlando Bell Ficklin, a lawyer and former U.S. representative, and Judge Constable. Together, they agreed to cancel the speech and urged the crowd to disperse.[4] As young attorneys, Constable and Ficklin had shared courtrooms with Abraham Lincoln.

By mid-afternoon, around 3 o’clock, Coles County Sheriff John H. O’Hair, a prominent leader among the local Copperheads, was preparing for the trial of an accused hog thief. Unfounded rumors had circulated that Union soldiers might attack the courthouse, so O’Hair arrived with reinforcements: two deputies, John Elsberry Hanks (his cousin) and Kesse Swango, along with two of his brothers. Hanks, notably, was a matrilineal relative of Abraham Lincoln.[5] Just weeks earlier, in February, William S. O’Hair, John’s cousin and sheriff of neighboring Edgar County, had been involved in a violent altercation with soldiers from the 12th and 66th Illinois regiments.[6]

Outside the courthouse, most of the crowd had dispersed, but Nelson Wells and seven associates, all from Edgar County, remained. Preparing to leave for California to prospect for gold, they had brought a wagon loaded with rifles and shotguns concealed beneath straw.

A local man named Robert Leitch attempted to mediate between the soldiers and Wells’s group. “[I] told them,” Leitch later recalled, “that I had conversed with the soldiers and knew that they intended to leave town and would not molest any person if left alone.” But Nelson Wells and Frank Tolen were unmoved. They replied that they had been badly treated by the soldiers and were “going to have revenge.”[7]

It remains unclear who fired the first shot. According to one account, shortly after 3:30 p.m., Pvt. Oliver Sallee accidentally bumped into Nelson Wells. Not recognizing him, Sallee tapped Wells on the shoulder and asked, “Are any of those damned Copperheads around here?”

“Yes, damn you,” Wells replied, drawing his pistol. “I am one!” Before anyone could react, Wells pulled the trigger, and smoke erupted from the barrel. The lead ball struck Sallee in the chest, and he staggered backward. As he fell, Sallee managed to fire his own pistol, hitting Wells, who groaned and stumbled past the circuit clerk’s office. He made it as far as Chambers and McCrory’s General Store before collapsing in a pool of blood.[8]

Gunfire quickly became general. Perhaps a dozen Union soldiers were around the courthouse, but they were badly outnumbered and outgunned. At the sound of the first shots, Col. Mitchell and Maj. Shubal York headed for the exit. York was a prominent Republican and abolitionist from Paris, Illinois. Just a month earlier his son, John Milton York, had killed a local Copperhead in Paris. Inside the courthouse, as chaos erupted, someone shot York in the back at point-blank range, mortally wounding him.[9]

Colonel Mitchell later described what happened in those first few moments. “Immediately on the report of Wells’ pistol I stepped out of the west door of the court-room, when 3 men with revolvers drawn, apparently expecting me, commenced firing, 2 of them running by me into the room. I caught one named Robert Winkler by the wrist as he was attempting to shoot me, turning his revolver down until he discharged all his loads.”[10] A bullet struck Mitchell’s watch and ricocheted painfully into his stomach, but the wound proved superficial.

Out in the street, John Gilbriath stopped Marcus Hill as he was leading his horses toward the safety of a nearby alley. “Hill, what in the hell do you think of this?” he asked, breathless.

“It’s pretty damned warm times!” Hill shot back.[11]

Some townspeople stepped in to defend the soldiers, and the fighting grew so intense that one soldier reportedly struck his attacker in the head with a brick.

As Judge Constable fled the courthouse, Sheriff O’Hair attempted to bring order by taking charge of the rioters. They formed a loose firing line at the southeast corner of the town square and continued to exchange gunfire. Most of the Union soldiers lay dead or wounded. As the chaos subsided, Col. Mitchell managed to telegraph Mattoon for reinforcements. Soon, 250 soldiers were on their way, and the Copperheads were riding out of town.

Though the riot had ended, the killing had not. A soldier and a civilian, W.A. Noe, apprehended John Cooper and brought him in front of E.A. Jenkins’ Dry Goods Store. But Cooper broke free and drew a concealed pistol from his belt. Noe fired a warning shot over his head. It was too late. Cooper, panicked, returned fire and was immediately gunned down from three directions. In the crossfire, young John Jenkins was struck by a stray bullet and bled to death soon after.[12]

All told, six Union soldiers were killed and four wounded; one Republican civilian was killed and three others wounded; and two Copperheads were killed with five others wounded. Although the Copperheads had surprised and overwhelmed the soldiers during the riot, their organization quickly unraveled in its aftermath. Several dozen were arrested, while others fled. Sheriff O’Hair escaped to Canada and did not return until after the war.

For this small Illinois town, March 28, 1864 has been remembered as the day when civil war truly came home.

————

M.A. Kleen is a program analyst and editor of spirit61.info, a digital encyclopedia of early Civil War Virginia. His article “‘A Kind of Dreamland’: Upshur County, WV at the Dawn of Civil War” was recently published in the Spring 2025 issue of Ohio Valley History.

Endnotes:

[1] Michael Kleen, “The Copperhead Threat in Illinois: Peace Democrats, Loyalty Leagues, and the Charleston Riot of 1864,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 105 (Spring 2012): 80.

[2] Charles Sumner to Francis Lieber, Jan. 17, 1863, Edward L. Pierce, Memoir and Letters of Charles Sumner, Vol. IV (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1894), 114.

[3] Stephen E. Towne, “‘Such conduct must be put down’: The Military Arrest of Judge Charles H. Constable during the Civil War,” Journal of Illinois History 9 (Spring 2006): 43-62.

[4] Charles H. Coleman and Paul H. Spence, “The Charleston Riot, March 28, 1864,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 33 (March 1940), 21.

[5] Richard K. Tibbals, “‘There has been a serious disturbance at Charleston…’: The 54th Illinois vs. the Copperheads,” Military Images 21 (July-August 1999), 13; Coleman and Spence, 20.

[6] John Scott Parkinson, “Bloody Spring: The Charleston, Illinois Riot and Copperhead Violence During the American Civil War” (Ph.D. diss., Miami University, 1998), 168-71.

[7] Charles H. Coleman, “Depositions Taken in Charleston, Illinois after the Charleston Riot of March 28, 1864,” Vol. I (Charleston: Illinois Circuit Court, 1939), 24.

[8] Tibbals, 12.

[9] Danny Briseno, “York family goes to war,” The Prairie Press (Paris, IL) 12 June 2017.

[10] The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I, Vol. XXXII, Part 1 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), 633.

[11] Robert D. Sampson, “‘Pretty Damned Warm Times’: The 1864 Charleston Riot and ‘the Inalienable Right of Revolution’,” Illinois Historical Journal 89 (Summer 1996): 99.

[12] “The Charleston Butchery,” Daily Illinois State Journal (Springfield, IL) 2 April 1864.

While on a much smaller scale than the 1863 New York City draft riot, this article effectively demonstrates the consequences of those tensions and divisions that were ongoing on the Northern homefront or the “fire in the rear” that Lincoln was so concerned about, and that Lee had tried multiple times to exploit during in attempted invasions of the North.