The Forgotten Story of the 2nd Engineers, Corps d’Afrique in Civil War Texas

ECW welcomes back guest author William J. Bozic Jr.

The 2nd Regiment Engineers, later reorganized as the 96th United States Colored Infantry, played a distinct role in the Union’s Gulf strategy during the American Civil War. Their service illustrates both the reliance on African American troops for technical and engineering duties and the strategic importance of Texas’s Gulf Coast in Union military planning. Unlike traditional infantry units, rather than combat operations the Corps d’Afrique Engineers undertook demanding and essential duties: constructing fortifications, repairing roads and wharves, and building the logistical backbone necessary for sustained military operations. Their labor and technical skill enabled the Union Army to project power into the Matagorda Bay region and establish footholds along the Texas coast in 1863-64.[1]

The Port Hudson siege (May 21-July 9, 1963) illustrated the need for more engineers in the Department of the Gulf. Organized in New Orleans, Louisiana on August 15, 1863 the regiment, composed largely of contrabands enlisted in the Crescent City, was initially attached to the Engineer Brigade, Department of the Gulf.[2] For several months, the unit remained on duty in Louisiana, but in December 1863 it was ordered westward into Texas. On December 5, 1863, the regiment moved to Matagorda Bay, initiating a period of concentrated service along the Texas coastline that lasted through April 1864.[3]

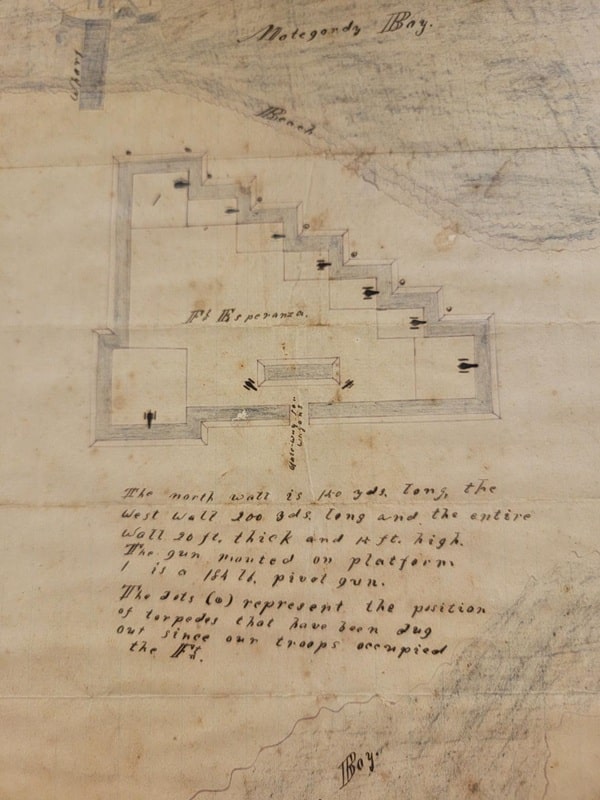

During this deployment, the 2nd Engineers engaged in extensive engineering work at multiple sites of strategic importance: De Crow’s Point, Fort Esperanza, Matagorda Island, and Pass Cavallo. These locations represented critical nodes in Union efforts to establish and maintain control over the Texas littoral.[4] The regiment’s tasks included constructing fieldworks, fortifications, and other defensive installations necessary to secure Union positions along the Gulf.

The area around and including Matagorda Island was primarily loose, shifting sand, so this was a sweat-and-muscle operation under fatiguing conditions. To add to the difficulty experienced by the 2nd Engineers, Matagorda Island and Matagorda Peninsula offered few natural resources: no timber for fuel or shelter, no fresh water, and little protection from storms. In such bleak and exposed conditions, the isolation, monotony, and unrelenting weather wore on the regiment’s endurance. Maintaining fires for warmth, repairing tents, and protecting stores from wind and salt became as vital as the construction work itself. In short, building on a coastal barrier island in wintertime meant fighting the land, the sea, and the sky all at once, a struggle against nature’s rawest forces, with little margin for comfort or delay.

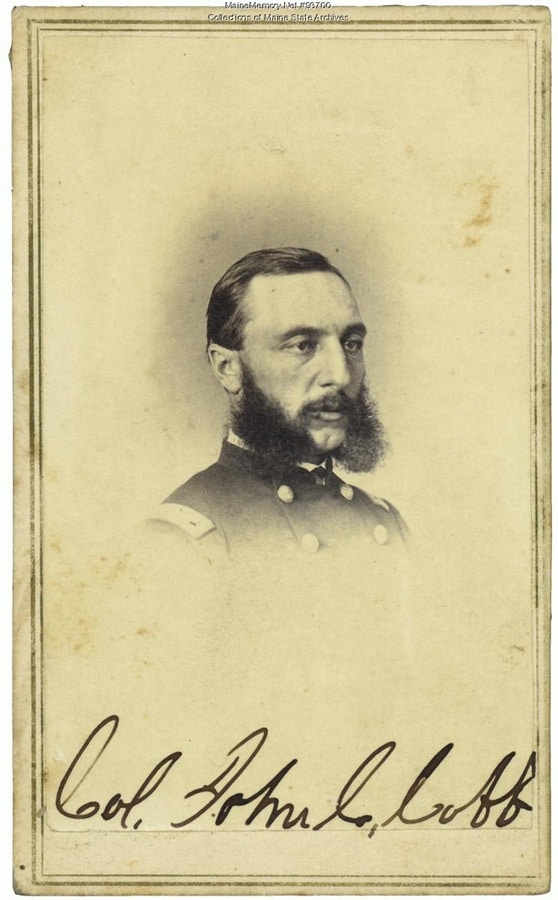

On April 4, 1864, the regiment was formally redesignated as the 96th United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.), part of the broader reorganization of Corps d’Afrique units into numbered U.S.C.T. regiments.[5] Despite this administrative change, their continued assignment to Texas coastal duty—particularly their engineering work on the Matagorda Peninsula—underscored the centrality of their Texas service to the regiment’s identity and contribution.[6] Amid these organizational changes and continued coastal duties, the character and direction of the regiment increasingly reflected the influence of its commanding officers, foremost among them Col. John C. Cobb.

In addition to the noteworthy Cobb, there were African American enlisted soldiers who never received recognition, but gave their lives for the Union cause. Of particular note are the following men from Co. K who died in the infamous Great Drowning on March 13, 1864, at McHenry Bayou[9]: Pvt. Alezar Adams, age 18; Pvt. Joseph Albert, age 18; Pvt. John Tolbert, age 25; and Pvt. Golden Wright, age 14, as well as Pvt. Lagrue LaBranch, age 28, of Co. E who was disabled during the construction of the pontoon bridge over McHenry Bayou on March 10, 1864. In total, nine received discharges and 18 members of the 2nd Engineers Corps d’Afrique/96th U.S.C.T. died along Matagorda Bay during the war in service to their country.[10]

Following their withdrawal from Texas, the 96th U.S.C.T. served in Louisiana and later participated in operations in Alabama, including construction operations during the siege of forts Gaines and Morgan (August 2–23, 1864) and the campaigns against Spanish Fort and Fort Blakely (March–April 1865).[11] These actions broadened their operational scope beyond Texas, yet their initial work along the Texas coast had already demonstrated the military utility of African American engineers in securing contested terrain. When the region ceased to be the focus of Federal attention, troops departed and destroyed all their works to keep them from falling into the hands of the Confederates. [12]

The regiment remained in service until January 29, 1866, performing garrison and engineering duties at Mobile and other points within the Department of the Gulf. While their later service extended across the Gulf, the Texas operations between December 1863 and May 1864 constituted the formative period of their history.[13]

In examining the military occupation of the Texas Gulf Coast, the contributions of the 2nd Regiment Engineers/96th U.S.C.T. highlight the Union’s reliance on African American troops. Their work not only reinforced Union footholds at Matagorda Bay and Fort Esperanza, but also provided a window into the larger dynamics of race, labor, and military necessity in Union-occupied Civil War Texas.[14] Despite their indispensable role in building defenses and facilitating Union occupation, the contributions of the 2nd Engineers have remained absent from public commemoration. Recognition through a Texas Historical Marker is currently underway to honor the men who labored, served, and died in Calhoun County, but also to broaden the narrative of Texas’s Civil War experience to include African-American soldiers whose work embodied both emancipation and engineering projects.[15]

William J. Bozic, Jr. earned a BA in History (1986) and an M.Ed. (1987) from the University of Florida. His area of expertise is the military actions in the Trans-Mississippi South during the Civil War, focusing on Texas and Louisiana. William works as a park guide for the National Park Service.

Endnotes:

[1] Frederick H. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion (Des Moines, IA: Dyer Publishing Co., 1908), 1737.

[2] Ibid. 1737.

[3] (The Official Records of Union and Confederate Armies in the War of the Rebellion. 1889, Series I Vol XXVI, Part 2, 71 & 102.)

[4] Edward T. Cotham Jr., Battle on the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston (Austin, TX: Texas State Historical Association, 1998), 203-7.

[5] U.S. War Department, General Orders No. 36 (Washington, DC: GPO, March 11, 1864)

[6] OR, Series I, Vol. XXXIV, Part 2, 529, 564, 637, 668, 771-2.

[7] Henry Augustus Shorey, The Story of the Maine Fifteenth: Being a Brief Narrative of the More Important Events in the History of the 15th Maine Regiment (Bridgton, ME: Bridgton News, 1890). Appendix X.

[8] OR, Series I, Vol. XXXIV, Part 2, 546,702-4.

[9] Carolyn S. Bridge, These Men Were Heroes Once: The 69th Indiana Volunteer Infantry (West Lafayette, Indiana: Twin Publications, 2005), 149-54.

[10] 2nd Regiment Engineers Corps d’Afrique/96th USCT file cards, NARA, Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served the United States Colored Troops: 96th USCT

[11] Dyer, 1737.

[12] OR, Series I, Vol. XXXIV, Part 1, 1011.

[13] Dyer, 1737.

[14] James G. Hollandsworth Jr. The Louisiana Native Guards: The Black Military Experience During the Civil War (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1995), 132-7.

[15] OR, Series I, Vol. XXVI, Part I, 508–510.

Interesting to read about African American soldiers in the ACW: And that their engineering effort is being highlighted.