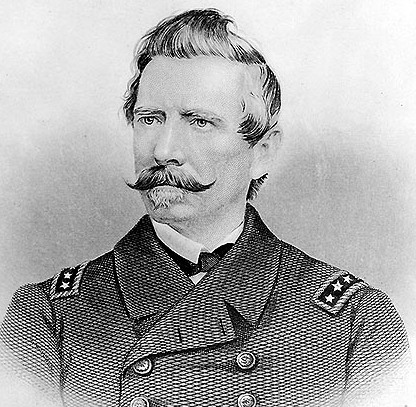

When the Weight of Secession Proved Too Much: Commander Edward Tilton’s Choice

Events were speedily progressing across North America by February 8, 1861. At that point, seven southern states of the United States of America had declared their secession from the old Union, and representatives gathered in Montgomery, Alabama, to create the Confederate States of America. The prospect of war quickly loomed as sides were chosen. Military, naval, and revenue officers of the United States had decisions to make, with hundreds ultimately choosing to resign their commissions and join the Confederacy (I have previously compared both sides’ officer corps and their antebellum experience here). Amongst the hundreds internally struggling with the path ahead was Commander Edward G. Tilton.

Tilton was a career naval officer. Delaware born, he first joined the navy on May 1, 1822. By 1861 his career included seventeen years at sea, and Tilton had risen to the grade of commander, equivalent to an army lieutenant colonel.[1] By the time of the secession crisis, he had served around the world in a dozen ships, including command tours on the brig Perry, sloop St. Louis, and sloop Saratoga.[2] In 1857, Tilton was temporarily assigned to the Treasury Department, joining the Lighthouse Board overseeing navigation aids alongside Captain William Shubrick and Commander Raphael Semmes.

The time assigned to the Lighthouse Board gave Tilton a much-needed break from his sea duty. It also allowed him to spend time with his family. Married to Josephine Harwood in 1833, the two had eight children. The 1860 census showed Tilton living in Washington D.C. with Josephine and five of their children. They also resided with Alice Williams, an 18-year-old mulatto woman acting as their household servant; the census lists Alice as a free woman.[3]

The secession crisis weighted heavily on Tilton’s mind, and he “had been laboring” on the Lighthouse Board “under and unfortunate depression of spirits, chiefly caused by the sectional difficulties existing throughout the country.”[4] On February 8, the same day the Confederacy was invented, Tilton “attended to the business of his office,” before returning home and conversing with several friends “about the prevailing topic” until dinner.”[5]

The commander’s friends left at dinnertime, and as Tilton’s family sat at the table, he went upstairs to his bedroom, an action which caused “no suspicion” to Josephine and the children.[6] Moments later, as the family ate, they heard a gunshot ring out and “a heavy fall overhead;” they rushed upstairs and found Commander Tilton “lying on the floor, which was deluged with his life-blood.”[7]

Learning of Tilton’s death, his comrade Raphael Semmes submitted a resolution to the Lighthouse Board attesting to the “scrupulous integrity, zeal, and ability” with which Commander Tilton tackled his duties.” The resolution was adopted by the Lighthouse Board and published by Treasury Secretary John Dix on February 13. The very next day, Semmes received a note from Montgomery stating, “On behalf of the Committee on Naval Affairs, I beg leave to request that you will repair to this place, at your earliest convenience.”[8] Semmes made that journey, ultimately becoming the Confederacy’s most famed naval officer, while his comrade Edward Tilton became one of the first naval officers to die because of the secession conflict, not from enemy fire but from the pressure of the situation itself.

Tilton’s death, in turn, caused continued pressure of its own on his eldest son, McLane. The 24-year-old lived with his parents, and was likely present in the house when his father went upstairs that fateful February 8. The shock of that night must have of weighed heavily on McLane. In response, less than one month after Tilton’s death, on March 2, 1861, McLane was commissioned a lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps. He served capably in the coming war and beyond, ultimately retiring a lieutenant colonel.

For Commander Edward Tilton, the United States ripping itself apart proved too much to bear. It took four years and another 700,000 deaths for the country to be reunited.

Endnotes:

[1] Register of the Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the Navy of the United States; Including Officers of the Marine Corps and Others, for the Year 1860 (Washington: 1860), 22-23.

[2] “The Late Capt. Tilton,” The Daily Exchange, Baltimore, MD, February 18, 1861; “The Late Capt. Tilton,” Daily National Intelligencer, Washington DC, February 16, 1861.

[3] Eighth Census of the United States, 1860, First Ward, Washington DC, for Edward Tilton, Josephine Tilton, McLane Tilton, Clara Tilton, Elizabeth Tilton, James Tilton, Gibson Tilton, and Alice Williams, Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[4] Suicide of a Naval Officer,” Daily Dispatch, Richmond, VA, February 11, 1861.

[5] “The Suicide of Capt. Tilton,” The Daily Exchange, Baltimore, MD, February 11, 1861.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Raphael Semmes, Memoirs of Service Afloat in the War Between the States (Baltimore: Kelly Piet and Company, 1869), 75.

Not a nice thing to do to his family

I often wonder at the personal demons that folks have when some geo-political event pushes them over the edge…