“Cold Blooded, Untruthful, and Unprincipled”: George Custer Through the Eyes of David Stanley

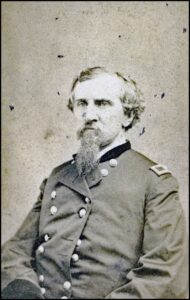

In 1873, the United States Army conducted the Yellowstone Expedition alongside surveyors with the Northern Pacific Railway. Colonel David S. Stanley commanded more than 1,500 men, comprised of a column of infantry, the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry Regiment, and a section of rifled artillery. Stanley previously served in several roles throughout the Civil War and, by 1864, commanded the U.S. Army’s IV Corps during the Tennessee Campaign. He was severely wounded during the battle of Franklin, but continued his career in the regular army. A little less than a decade later, he came face to face with one of the war’s most recognizable figures, George Armstrong Custer. Just as the “Boy Colonel” cemented his reputation alongside his Wolverines, so, too, had Stanley’s command proven its mettle in the war.

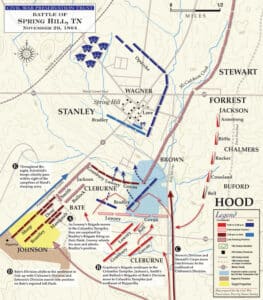

Following the reassignment of Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard, Stanley assumed command of the Army of the Cumberland’s IV Corps and led three hardened divisions into Tennessee in pursuit of Confederate Gen. John Bell Hood. On November 29, 1864, Stanley and 2nd Division under the command of Brig. Gen. George Wagner marched at breakneck speed to Spring Hill to protect vital supplies and prevent Hood from outflanking Maj. Gen. John Schofield’s 28,000-man army in Columbia.

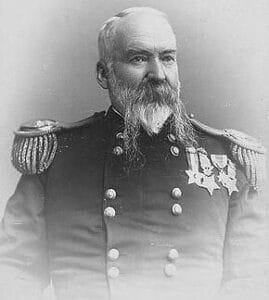

As one of Wagner’s brigades raced to the north side of the village, another assumed a position east of the Columbia Pike fronting the Rally Hill Pike and approaches from the Lewisburg Pike. In the center, Stanley occupied the home of Martin Cheairs for use as the IV Corps headquarters. The IV Corps’ artillery rolled up the Columbia Pike, and as they rattled forward, Stanley placed Wagner’s 3rd Brigade under Brig. Gen. Luther P. Bradley on a wooded hilltop just south of Lane’s position.

Just after 4:00 p.m., Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s Confederate division launched a menacing attack against Bradley’s line. As his men struggled to hold their position, a bullet tore through Bradley’s shoulder. So severe was his wound that he was removed from the field, and command of his shattered brigade fell to Col. Joseph Conrad of the 15th Missouri. Bradley’s wound sidelined him for the duration of the war.

As Bradley was led away to Nashville, Stanley and the balance of Wagner’s division, including the rallied portions of Bradley’s brigade, fought off Hood’s attempted flanking maneuver. In his memoirs, Schofield stated, “the gallant action of Stanley and his one division [Wagner’s]” could not be “over-estimated or too highly praised.”

Night fell, and confusion, exhaustion, and command paralysis saddled the Confederates. While Hood’s men encamped astride the Columbia Pike, Schofield and Stanley’s troops marched from Columbia through Spring Hill and on to Franklin. Captain Henry Castle, another IV Corps soldier, in an address delivered to the Minnesota Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, noted that, “Nashville, Louisville, Cincinnati, and Chicago were defended at Spring Hill.”[1]

As recently as 2020, historian Stephen Davis stated that “the ‘battle of Spring Hill,’ as it has been called, was not much of one, certainly in terms of casualties.” Do casualties define what is classified as a battle? Not entirely. Rather, what happened next secured Spring Hill’s importance. Perhaps the best way to judge the importance of Spring Hill is to understand what spawned from it. Spring Hill paved the way for a far bloodier, knock-down, drag-out fight on the afternoon of November 30, 1864.[2]

Disaster fell upon Wagner’s division at Franklin when Hood’s Army, having chased Schofield north, assembled for battle and charged their forward position south of the U.S. Army’s main defenses. As Wagner’s two brigades under Conrad and Col. John Lane withdrew, the Confederate advance stayed hot on their heels. Bolting over the earthen defenses, some of Wagner’s men turned and prepared to stand their ground against the tidal wave of Rebels. Others, however, continued their stampede toward town and the crossings over the Harpeth River.

When he heard the commotion, Stanley mounted his horse and rode into the confusion. He attempted to rally the men of the IV Corps. Stanley claimed that he observed the Army of the Cumberland’s “old soldiers” as they “sprang to their feet and shouted, ‘Come on, we can go anywhere the General can!’ and with a rush we retook our lines.” Just as the Federal counterattack began to materialize, a Confederate bullet struck Stanley in the neck. He was removed from the field and did not return to command until February 1865. Two months later, Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, President Lincoln died, and the war, after four years, came to an end.[3]

In the summer of 1873, Stanley was placed in command of the Yellowstone Expedition. As his 1,530-man force coalesced, he was reunited with IV Corps veteran Luther P. Bradley, then a colonel in the regular army. Stanley’s second in command was none other than George Custer, the commander of the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry and one of the most famous men in the United States.

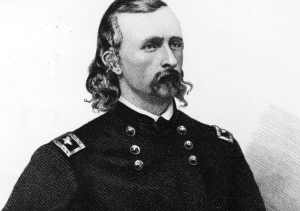

By the time the American Civil War ended, it had solidified the reputations of several individual officers and made figures such as Grant, Lee, Sherman, and Jackson household names. Among the most famous soldiers to come out of the war was Brig. Gen. George A. Custer. The youthful, romantic vision of the cavalryman captured the imagination of his contemporaries and even modern audiences. His image has been shaped by his rapid ascent through the ranks, battlefield derring-do, Errol Flynn’s portrayal of him in They Died with Their Boots On, and his demise at the battle of the Little Bighorn.

Custer, though, had his fair share of critics both in and out of the army, and how he is remembered today is drastically different than the dazzling Flynn portrayal. So, what did David Stanley think of Custer? In a June 29, 1873, letter to his wife, Stanley concluded:

I have seen enough of him to convince me that he is a cold blooded, untruthful and unprincipled man. He is universally despised by all the officers of his regiment excepting his relatives and one or two sycophants. He brought a trader in the field without permission, carried an old negro woman, and cast iron cooking stove, and delays the march often…I will try, but am not sure I can avoid trouble with him.

Two days later, Stanley wrote:

I had a flurry with Custer as I told you I probably would…Without consulting me he marched off 15 miles, cooly sending me a note to send him forage and rations. I sent after him, ordered him to halt where he was, to unload his wagons, and send for his own rations and forage, and never to presume to make another movement without orders.

I knew from the start it had to be done, and I am glad to have so good a chance, when there could be no doubt who was right. He was just gradually assuming command, and now he knows he has a commanding officer who will not tolerate his arrogance.[4]

This only added fuel to a budding feud between the two officers. Custer privately wrote to his wife about Stanley’s poor behavior on campaign and his ill fitness for command. Stanley was no longer the trim and cutting soldier he had been a decade prior. Older, more bitter over wartime rivalries and army politics, Stanley took to whiskey to calm his nerves. His prickly temper grew worse. Stanley placed Custer under arrest and declared him “the most insubordinate and troublesome officer I have ever dealt with.” The two continued to quarrel on and off for the next two months until, in September, Custer informed Libbie that “since my arrest, complete harmony exists between Gen’l Stanley and myself.”[5]

Three years passed. Custer’s once-famous golden locks looked more like thin strands tucked under his wide-brimmed hat. Custer fumbled into a political duel with President Ulysses S. Grant and narrowly avoided being removed from the army entirely after his arrest in Chicago following his involvement in the Belknap Impeachment proceedings. Only the intervention of his old friend and commander, Gen. Philip Sheridan, and Maj. Gen. Alfred Terry saved his career.

Just before he launched his final campaign as part of Terry’s command in the Dakota Territory, Custer remarked to William Ludlow, “I got away with Stanley, poor sot, so I suppose to be able to swing clear of Terry.” As the two parted, Custer left Ludlow with a haunting farewell, “I’m going to clear my name or leave my bones on the prairie.”[6]

A little less than a month later, Custer’s bones lay beneath the soil of the Little Bighorn battlefield before, in 1877, he was reburied at West Point.

Stanley and Bradley both continued in the service. The latter took command of two districts in Wyoming from 1874 to 1876 and was present at the killing of the Indian warrior, Crazy Horse. From 1879 to 1884, Bradley served as the colonel of the 13th Infantry Regiment and led those men in Louisiana and Georgia before he took command of the District of New Mexico. In 1886, at the age of sixty-four, he retired from the U.S. Army and died on March 13, 1910. Stanley, like Bradley, made a career out of the army and retired in 1892, having finally received the Medal of Honor for his actions at Franklin. He died ten years later and was buried in the United States Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home National Cemetery.

[1] John M. Schofield, Forty-Six Years in the Army, p. 177-178; Henry Castle, “Opdycke’s Brigade at the Battle of Franklin” Glimpses of the Nation’s Struggle, 6th Series, Papers Read Before the Minnesota Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, 390, 174.

[2] Stephen M. Davis, Into Tennessee and Failure: John Bell Hood, 127.

[3] David S. Stanley, An American General, 177.

[4] “Letter from David S. Stanley to Anna Stanley” July 28, 1873, quoted in David S. Stanley, Military Careers of Major-General David Sloane Stanley, U.S.A., (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1917), 194-196.

[5] D.A. Kinsley, Custer: A Soldier’s Story, (NY: Promontory Press, 1988), 459-460.

[6] Kinsley, Custer, 500.

There was much disgusting behavior amongst the Federal officer corps during the war.

I wasn’t aware of this clash between General Stanley and Custer, but it certainly provides interesting insight into both men. Thank you!

thanks — great piece … Stanley’s appraisal confirms what Custer was all about — a slightly above average cavalryman during the war … and a troublesome prima donna thereafter who pretty much did whatever he wanted and rarely met a commanding officer he didn’t like.

“His prickly temper grew worse.” Knowing Stanley I gasped at that line. Still, I love Stanley’s brutal honesty. Never a dull moment!