Echoes of Reconstruction: Stonewall’s Theologian Robert Dabney on Black Ministers During Reconstruction

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome back Patrick Young, author of The Reconstruction Era blog.

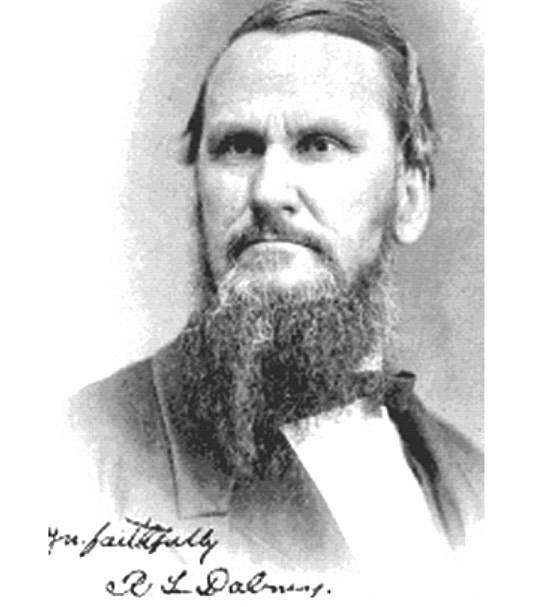

Robert Lewis Dabney was a noted Southern Presbyterian who served as both a minister of that faith and a professor of systematic theology. Before the Civil War he served as an intellectual advocate for the Confederate position in support of slavery. In 1862 he joined the Confederate military as a chaplain and he soon became adjutant general to Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. After the war he authored the leading biography of his old commander.

The end of the war brought major changes to Virginia’s social structures. Slavery was ended and African Americans were working to establish themselves through free labor, legal marriage, the maintenance of families, the purchase of property, and their incorporation into the Christian religious life. Most former slaves had not had the chance to worship at churches of their own before emancipation. Some white-dominated denominations considered opening their doors to freedpeople, even while many white members strongly objected. The Southern Presbyterians took up the incorporation of Blacks into their congregations in 1867. One of the most prominent ministers to oppose elevating Blacks to the ministry was Robert Dabney. The theologian spoke at the November 1867 Virginia Synod of the denomination in opposition to a resolution to ordain qualified Black ministers.

Dabney opened by insisting that the assembled Presbyterians all thought along the same lines as he did, but that for reasons of what might now be called “political correctness” they were unwilling to express their true feelings regarding Black Christians. He then described his own feelings towards Southern Blacks:

“I have had enough of declarations and manifestations of special interest in, and love for, the souls of ‘the freedmen,’ under existing circumstances. When I see them almost universally banded to make themselves the eager tools of the remorseless enemies of my country, to assail my vital rights, and to threaten the very existence of civil society and the church, at once; I must beg leave to think the time rather mal appropos [inopportune] for demanding of me an expression of particular affection. If I gave it, I should not expect any one to credit it. Were you traveling in Mexico, assailed by bandits, wounded, dragged from your carriage, bound to a tree, and looking with a bleeding pate upon the rifling of your baggage, if you were called on to state, then and there, how exceedingly you desired the spiritual good of the yellow-skinned barbarians who were persecuting you, it is to be presumed that you would beg to be excused, under the circumstances. So I, for one, make no professions of special love for those who are, even now, attempting against me and mine the most loathsome outrages. If I can only practice the duty of forbearance successfully, and say, “Father, forgive them; they know not what they do,” I shall thank God for his assistance in the hour of cruel provocation.”

Next, Dabney described the debate over the ordination of Black Southern Presbyterian ministers as worthless because he did not believe that Blacks wanted to serve as clergy in a non-“Yankee” denomination. He argued:

“I oppose the agitation of this whole subject, because it is unpractical. The only appreciable effect it can have will be to agitate, and so to injure our existing churches. On the basis you profess, (that is, to exact impartially of the black man, as of the white, full compliance with the requirements of our standards,) the negro is not coming to you. …He wholly prefers the Yankee to you. So that this whole zealous discussion presents us in the ridiculous light…of two school boys, who after a stiff fight over a bird’s nest, ascertain that it is too high for either of them to reach. Perhaps this is the very thought which prompts some to support this scheme; that they may disarm Abolitionist criticism by seeming to obey their imperious dictation, and to open the door of our ministry to negroes; while they rely on the negroes’ hostility, to protect us from their entrance; a result which they would no more accept than I do. Thus they hope to “save their manners and their meat” at once. Is this candid? Is it manly? Is it Christian honour?

“But I warn these gentlemen, that they will be deceived by the result. While I greatly doubt whether a single Presbyterian negro will ever be found to come fully up to that high standard of learning, manners, sanctity, prudence, and moral weight and acceptability, which our constitution requires, and which this overture professes to honour so impartially; I clearly foresee that, no sooner will it be passed than it will be made the pretext for a partial and odious lowering of our standard, in favour of negroes.”

Dabney then sought to use fear of Black control of the Presbyterian Church to motivate the synod to crush the movement for Black ordination. While the synod was only considering allowing some Blacks to become ministers, Dabney repeatedly referred to any people of African descent raised to the ministry as the church’s new “black rulers.” Here is one such reference [The bolding is mine]:

“I oppose the entrusting of the destinies of our Church, in any degree whatever, to black rulers, because that race is not trustworthy for such position. There may be a few exceptions; (I do not believe I have ever seen one, though I have known negroes whom I both respected and loved, in their proper position) but I ask emphatically: Do legislatures frame general laws to meet the rare exceptions? or do they adjust them to the general average? Now, who that knows the negro, does not know that his is a subservient race; that he is made to follow, and not to lead; and his temperament, idiosyncrasy, and social relation, make him untrustworthy as a depositary of power? Especially will we weigh this fact now, unless we are madmen; now, when the whole management to which he is subjected is so exciting, so unhealthy, so intoxicating to him; and when the whole drift of the social, political, and religious influences which now sway him, bear him with an irresistible tide, towards a religious faction, which is the deadly and determined enemy of every principle we hold dear. Sir, the wisest masters in Israel, a John Newton, an Alexander, a Whitefield, have told us, that although grace may save a man’s soul, it does not destroy his natural idiosyncrasy, this side of heaven. If you trust any portion of power over your Church to black hands, you will rue it. Have they not done enough recently, to teach us how thoroughly they are untrustworthy? They have, in a body, deserted their true friends, and natural allies, and native land, to follow the beck of the most unmasked and unprincipled set of demagogues on earth, to the most atrocious ends. They have just, in a body, deserted the churches of their fathers. They have usually been prompt to do these things, just in proportion to their religious culture and to our trust in them. Is not this enough to teach us, that if we commit our power to that race, in these times of conflict and stern testimony, possibly of suffering for God’s truth, it will prove the “bruised reed, which when we lean upon it will break…”

Rev. Dabney also warned that lay Presbyterians were angry that their leaders were even considering ordaining Blacks both because they did not believe a Black man could be qualified, and because they understood that this novelty was only being considered because the Northern enemies of slavery were insisting on it. Dabney said that the attack on slavery had been used before the war by Northerners to try to control the power of Southern whites. He said it had been used to bring on the war, and that after Appomattox it continued to be a weapon against the Southern white social structure. Here is some of what Dabney said, in his own words:

“For a generation, Southern Christians have seen the negro made the pretext of a malignant and wicked assault upon their fair fame, and their just rights. At length, he has been made the occasion of a frightful war, resulting in the conquest and ruin of the land, and the overthrow of all our civil rights. And now, our conquerors and oppressors, after committing the crime of murder against our noble old commonwealth, and treading us down with the armed heel, are practicing to add to every atrocious injury, the loathesome insult of placing the negro’s feet upon our necks.

The removal of discriminatory bars on Blacks would lead to racial equality. Dabney warned that this equality was in fact “negro supremacy.” He argued: “This day we are threatened with evils, through negro supremacy and spoliation, to whose atrocity the horrors of the late war were tender mercies. And these ebony pets of this romantic philanthropy, this day lend themselves in compact body, with an eager and almost universal willingness, to be the tools of this abhorred project; the scorpion—say rather the reptile lash in the hands of our ruthless tyrants. But our brethren, turning heartsore and indignant from their secular affairs, where nothing met their eye but a melancholy ruin, polluted by the intrusion of this inferior and hostile race, looked to their beloved Church for a little repose. …There, at least, Virginians may meet and act, without the disgust of negro politics and the stain of negro domination. Will you, dare you say to them, no?

Northerners who worked for Black political equality, Dabney said, hoped that once that was achieved it would make the former slave socially equal with the whites. The sexual “amalgamation” of the two races would then begin as whites and blacks formed interracial families, a horrific occurance. Dabney said:

“When once political equality is confirmed to the blacks, every influence will tend towards that other consummation, social equality, which they will be so keen to demand, and their demagogues so ready to grant, as the price of their votes. Why, sir, the negroes recently elected in, my own section, to represent in the pretended convention, districts once graced by Henry and Randolph, are already impudently demanding it. He must be “innocent” indeed, who does not see whither all this tends, as it is designed by our oppressors to terminate. It is (shall I pronounce the abhorred word?) to amalgamation! Yes, sir, these tyrants know that if they can mix the race of Washington, and Lee, and Jackson, with this base herd which they brought from the pens of Africa; if they can taint the blood which hallowed the plains of Manassas, with this sordid stream, the adulterous current will never again swell a Virginian’s heart with a throb noble enough to make a despot tremble. But they will then have, for all time, a race supple and grovelling enough for all the purposes of oppression.

“Once a white family worshiped under the spiritual direction of a Black man, how could the church insist that the daughters of that family not marry a person of the same race as the minister?”

Dabney demanded that the Presbyterians not follow the fashion of the years and grant equal rights to Black congregants. Instead he urged the church to uphold its conservative principle of racial inequality that had undergirded it for more than two hundred years. He argued: “Now I ask emphatically, what change has taken place in the black race, to make them more fit for ruling over white churches than they then were? Are they any wiser, any more religious, any purer, any more enlightened now? Nay; the only change is a violent revolution, made by the sword, by which, as every intelligent Virginian knows, they have been only injured in character, as in destiny. Hence, I cannot see why an ecclesiastical policy towards them which was wise, and right, and scriptural then, is not at least as much so now. But it is said: “Then they were by law slaves; now they are by law free.” I reply, does Christ’s kingdom wait on the politicians and conquerors of the world, to be told by them how she must administer her sacred charge? …I invoke it here: this is the place for it to assert itself, where I demand for the church the right to carry out still her own scriptural polity towards the Africans, as she has practiced it for 150 years, justified by all sound Presbyterians, North and South; and to pursue the even tenour of her way, regardless of the decision of the sword and faction…”

Dabney ended by insisting that if there were sufficient Black Presbyterians to support Black ministers, they should be encouraged to separate from the Southern Presbyterians and form their own churches in their new denomination. He ended his address by saying:

But I would make no black man a member of a white Session, or Presbytery, or Synod, or Assembly; nor would I give them any share in the government of our own church, nor any representation in it. “It is confusion.”

Christ, what an asshole.

Interesting read though.

Dabney’s beliefs are still followed today by a small minority. This doctrine is called Kinism in which Christians are instructed to value their family and ethnic group over anyone else. These Kinism religions are most commonly associated with Christian white supremacy.

Kin, Kluture, and Kinism the three Ks.

White-hooded verbiage.