Contraband Camp and Hospital, Washington, D.C.

On a parcel of swampy land in northwest Washington, D.C., a tented camp and hospital stood that served thousands of the formerly enslaved and Black soldiers of the U.S.C.T. during the American Civil War. Known as Contraband Camp, it contained one of the few hospitals that treated Black people in the city and whose staff, including nurses and surgeons, were primarily African American. More than half of the Black surgeons who served during the Civil War spent time at Contraband Hospital, later Freedmen’s Hospital.

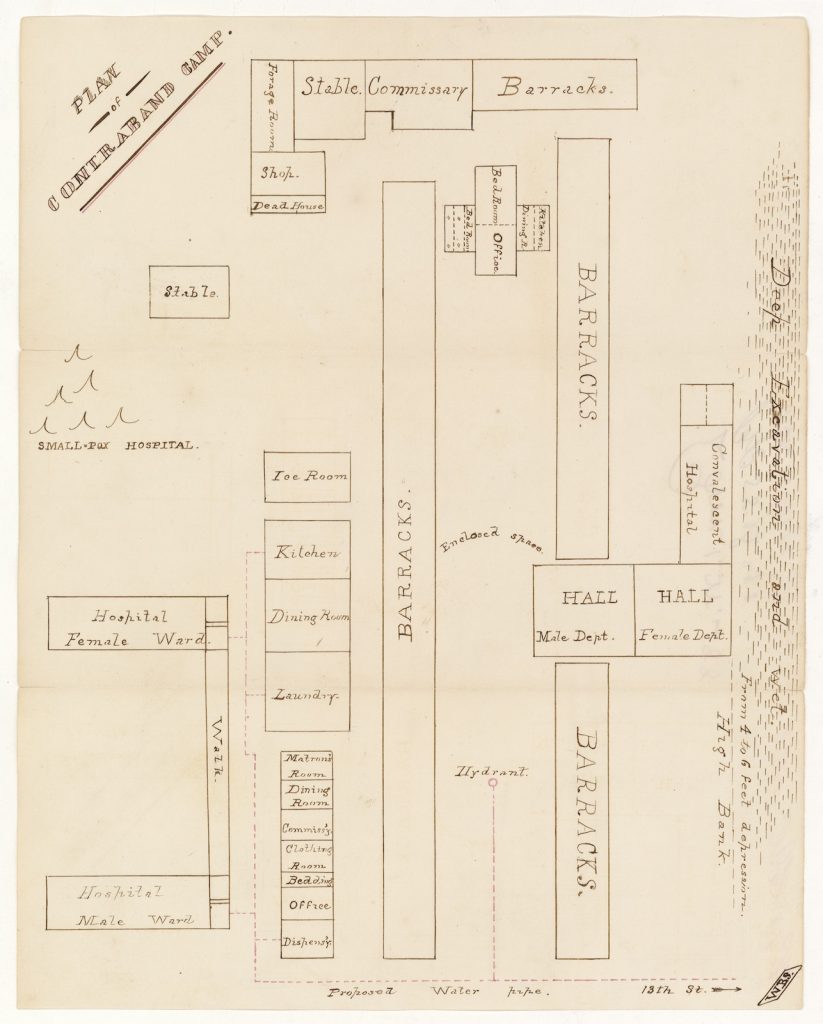

This “Plan of Contraband Camp” is the only known image that documents the layout and grounds of the camp and hospital. Created in 1863, it was part of a proposal to connect the camp to the city’s water system in order to replace the only source of water, an unsanitary well that was dry part of the year. Although the plan was rejected, this diagram provides a look at the camp’s layout including barracks, the tented small pox hospital, the camp’s kitchen and food services, and the hospital wards for females and males. The pension depositions of Black nurses who served at the hospital corroborate the placement of buildings and location of services shown in the diagram.

Betsey Lawson who served as a nurse at Contraband Hospital provided a deposition in support of the pension application of fellow Black nurse Maria Page. Lawson describes how she met Page as a result of their daily work routine and the camp’s layout. She said, “I could stand in the door of the barracks and talk to her at the tents where she was a nurse, but there was a guard who walked a beat between the two places. The meals for the smallpox tents were all supplied from the barracks where I nursed the sick, all cooked by the same cooks. It was the duty as the nurses from the smallpox tents to come after the meals for their patients. In that way I became acquainted with Maria Page.”[1]

Established in 1862, Contraband Camp survived for over a year before being disbanded in December 1863, but the hospital continued to provide medical care to Black civilians and soldiers. Control of the hospital was transferred from the U.S. Army to the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands in 1864. It moved several times over the next few years from its original location at R, S, 12th and 13th Streets Northwest, finally settling at the site of Howard University in 1868 when it became the teaching hospital for its newly formed medical department.

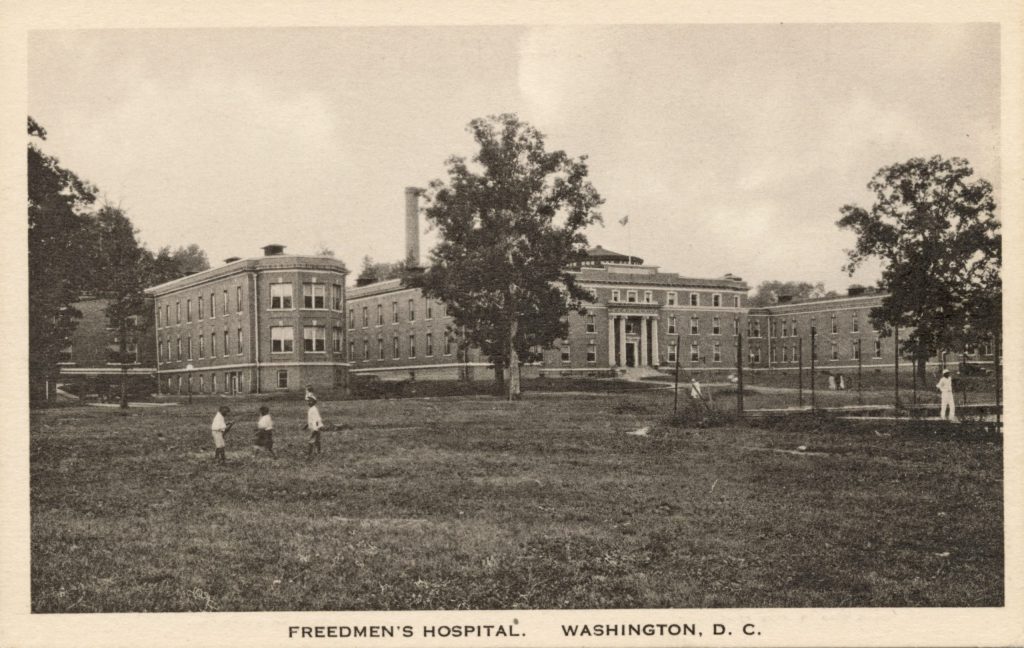

Freedmen’s Hospital continued to serve the population of Washington, D.C. over the next 100 years, expanding its facilities and offering its services to both Black and white patients. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy signed a bill that would officially transfer the hospital to Howard University. Moving into new facilities in March 1975, Freedmen’s Hospital officially became known as Howard University Hospital.

Contraband and Freedmen’s Hospital endured through the Civil War and into the 21st century not only because of the needs of the community, but because of the women and men who dedicated themselves to the hospital’s survival. The hospital’s ability to withstand the test of time can best be articulated by a quote from The Story of Freedmen’s Hospital: “It owed its longevity…most of all to the dedication of men who committed their careers to its survival and growth. They refused to let the nation forget that this was no ordinary hospital, but part and symbol of a larger commitment to those America had enslaved and grudgingly freed.”[2]

————

[1] Betsey Lawson, deposition for pension application of Maria Page, file #1174096, January 26, 1897, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[2] Holt, Thomas, et. al. The Story of Freedmen’s Hospital, 1862-1962. Washington, D.C.: Howard University, 1975,