CHAPTER FOUR: “’The Heavyest Blow Yet Given the Confederacy’:

The Emancipation Proclamation Changes the Civil War”

by Kevin Pawlak

Commentary · Images · Additional Resources · Suggested Reading · About the Author

Commentary

By Brian Matthew Jordan, co-editor, “Engaging the Civil War” Series

Students will sometimes ask me, “If you could time travel and witness one Civil War event, what would it be?” I’ll confess that I did not have a ready answer the first few times they posed the question. Despite my insatiable curiosity—the essential trait of any historian—I have no desire to return to the events about which I research and write. While the historian must approach the past from the perspective of historical actors, the British historian Simon Schama has done too much to persuade me that a keen sense of “imagination” is necessary for our work. So I rummaged my brain for those bits of theory and philosophy that would help me to explain why becoming a witness to an historical event would hardly aid my attempt to narrate it.

Before long, though, I realized there would be no harm in essaying an answer. The first response that came to mind was the remarkable scene depicted by Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson in his 1869 memoir, Army Life in a Black Regiment. A veteran of the abolitionist movement and bankroller of John Brown’s Harper’s Ferry raid, it was Higginson who, in 1862, assumed command of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, the first federally recognized African American regiment. On the first of January 1863, the colonel summoned his troops to “a beautiful grove,” the majestic branches of sturdy, live oaks interlocking overhead.

On a “platform” erected for the day, a simple ceremony “began at half-past eleven o’ clock.” Following a prayer, W.H. Brisbane, a South Carolina abolitionist, read aloud the “careful prose” of the Emancipation Proclamation. When he had finished, “the colors were presented to us by the Rev. Mr. French.” “All of this was according to the programme,” the colonel wrote. “Then following an incident so simple, so touching, so utterly unexpected and startling, that I can scarcely believe it on recalling, though it gave the keynote to the whole day.”

“The very moment the speaker had ceased, and just as I took and waved the flag, which now for the first time meant anything to these poor people, there suddenly arose, close beside the platform, a strong male voice (but rather cracked and elderly), into which two women’s voices instantly blended, signing, as if by an impulse that could no more be repressed than the morning note of the song-sparrow: ‘My country, ‘t is of thee, Sweet land of liberty, Of thee I sing!’”

Colonel Higginson and others on stage were startled. “Firmly and irrepressibly the quavering voices song on, verse after verse,” he remembered. “Others of the colored people joined in; some whites on the platform began, but I motioned them to silence. I never saw anything so electric; it made all other words cheap; it seemed the choked voice of a race at last unloosed.” “The life of the whole day,” he concluded, “was in those unknown people’s song.”

Whenever I teach the Civil War lecture course, I linger a few moments beneath those moss-draped branches. It seems to me the story of emancipation in microcosm. The work of pulling up the “peculiar institution” required the participation of whites and blacks—of soldiers, slaves, and abolitionists alike. It was not a decree pronounced from on high, but rather, as recent historians have demonstrated, a process made real on the ground.

For the former slaves who melted away at the end of the ceremony, emancipation was a most uncertain beginning. One week after the stirring ceremony, Higginson told his diary that he “dare not yet hope that the promise of the President’s Proclamation will be kept.” After all, he remarked, “revolutions may go backward; and the habit of injustice seems so deeply impressed upon the whites, that it is hard to believe in the possibility of anything better.” As Chandra Manning has pointed out, promising neither citizenship nor racial equality—and utterly contingent on the triumph of Union arms—it remained to be seen just what kind of “turning point” emancipation would be.

* * *

By Christopher Kolakowski, Chief Historian, Emerging Civil War

Emancipation was the key issue in a political firestorm that almost, engulfed the Lincoln Administration in the fall of 1862. Battlefield results both intensified and calmed the storm. I explain more in my Emerging Civil War Digital Short, “The Union’s Great Crisis: The Fall of 1862.”

* * *

Dan Vermilya, author of the Emerging Civil War Series book That Field of Blood: The Battle of Antietam, offers his thoughts on the Emancipation Proclamation as a turning point here.

Images

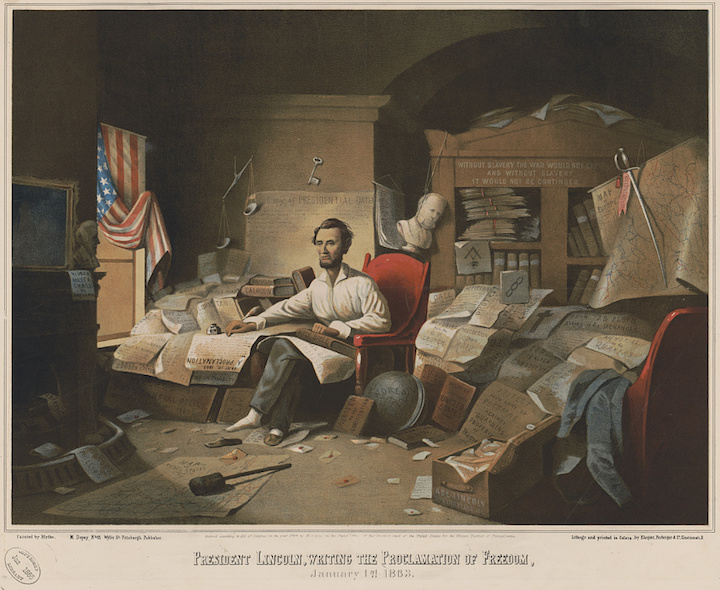

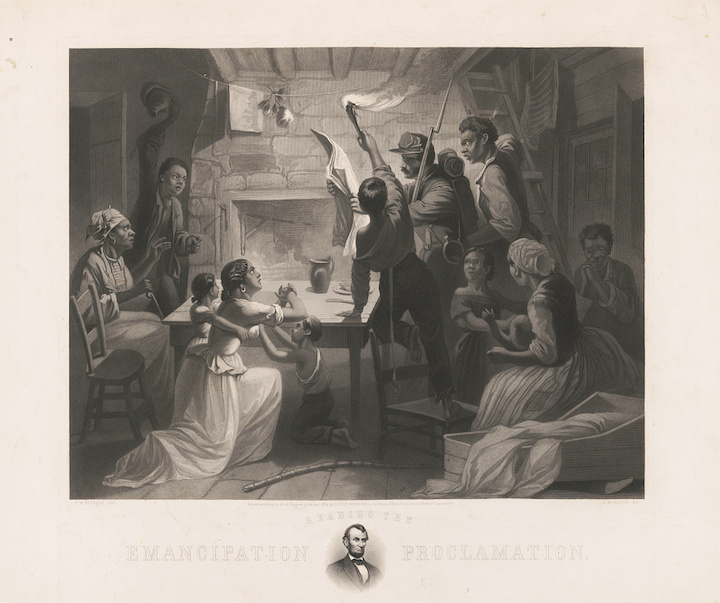

After the importance of the Emancipation Proclamation became widely appreciated, lithographs of the document became popular souvenirs. Perhaps to compensate for the business-like tone of the writing, the sheets were decorated with elaborate images to commemorate Lincoln and the abolition of slavery. For closer views of each, view high-res versions at the Library of Congress: top left, top right, bottom left, bottom right. Other similar lithographs are also available for viewing.

* * *

President Lincoln, writing the Proclamation of Freedom. January 1st, 1863. From the Library of Congress: “A print based on David Gilmour Blythe’s fanciful painting of Lincoln writing the Emancipation Proclamation. Contrary to the title, the proclamation was issued in 1862 and went into effect in January 1863. In a cluttered study Lincoln sits in shirtsleeves and slippers, at work on the document near an open window. His left hand is placed on a Bible that rests on a copy of the Constitution in his lap. The scene is crammed with symbolic details and other meaningful references. A bust of Lincoln’s strongly Unionist predecessor Andrew Jackson sits on a mantlepiece near the window at Lincoln’s right. A bust of another former President, James Buchanan, who was widely viewed as ineffectual against secessionism, hangs by a rope around its neck from a bookcase behind Lincoln. The scales of justice appear in the left corner, and a railsplitter’s maul lies on the floor at Lincoln’s feet.”

* * *

From the Library of Congress: “Print shows a reenactment of Abraham Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation on July 22, 1862, painted by Francis B. Carpenter at the White House in 1864. Depicted, from left to right are: Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of War; Salmon P. Chase, Secretary of the Treasury; President Lincoln; Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy; Caleb B. Smith, Secretary of the Interior; William H. Seward, Secretary of State; Montgomery Blair, Postmaster General; and Edward Bates, Attorney General. Painting of Simon Cameron appears on the left; a painting of Andrew Jackson is barely visible behind the chandelier.”

* * *

A steel engraving, circa. 1864, that accompanied a pamphlet about the Emancipation Proclamation. Titles “Reading the Emancipation Proclamation,” the image depicts a Union soldier reading the proclamation aloud while slaves cluster around him showing expressions of hope an incredulity. (credit: Library of Congress)

* * *

As part of ECW’s 2017 “Battlefield Markers and Monuments” series, Steward Henderson discussed the significance of the Emancipation Memorial in Washington, D.C. (credit: Library of Congress)

Additional Resources

See a facsimile of the Emancipation Proclamation at the Library of Congress’s website.

Kevin Pawlak first wrote about the Emancipation Proclamation for ECW in a two-part series, “‘The World Will Little Note, Nor Long Remember’: The Battle of Shepherdstown and the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.”

Chris Mackowski offered an overview of the Emancipation Proclamation, which he called “Lincoln’s most inelegant writing—and most important,” in a post that served as the basis for the introduction to Kevin’s essay in the Turning Points book.

The Civil War Trust’s “In4” video series features a segment about the Emancipation Proclamation, hosted by historian Hari Jones, that you can watch here. The “In4” series also features a segment about the battle of Antietam, hosted by Garry Adelman, that you can watch here.

You can visit Antietam National Battlefield online here.

You can visit the Fredericksburg National Battlefield, part of Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, online here.

You can visit Stones River National Battlefield online here.

Suggested Reading

· Guelzo, Allen C. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America (Simon & Schuster, 2004)

· McPherson, James. Crossroads of Freedom: Antietam (Oxford University Press, 2002)

· Medford, Edna Greene. Lincoln and Emancipation (Southern Illinois University Press, 2015)

About the Author

Kevin Pawlak is the education specialist for the Mosby Heritage Area Association and is a licensed battlefield guide at Antietam National Battlefield. He previously worked at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park and interned with the Papers of Abraham Lincoln at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library in Springfield, Illinois. Pawlak serves on the boards of directors of the Shepherdstown Battlefield Preservation Association and the Save Historic Antietam Foundation and is on the advisory board for the George Tyler Moore Center for the Study of the Civil War at Shepherd University. He is the author of Shepherdstown in the Civil War: One Vast Confederate Hospital (2015).

Kevin Pawlak is the education specialist for the Mosby Heritage Area Association and is a licensed battlefield guide at Antietam National Battlefield. He previously worked at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park and interned with the Papers of Abraham Lincoln at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library in Springfield, Illinois. Pawlak serves on the boards of directors of the Shepherdstown Battlefield Preservation Association and the Save Historic Antietam Foundation and is on the advisory board for the George Tyler Moore Center for the Study of the Civil War at Shepherd University. He is the author of Shepherdstown in the Civil War: One Vast Confederate Hospital (2015).