CHAPTER FOUR: The Creation of Fredericksburg National Cemetery

Photos · Additional Resources

Photos

Brig. Gen. Thomas Meagher led the Irish Brigade at the Battle of Fredericksburg.

Brig. Gen. Thomas Meagher led the Irish Brigade at the Battle of Fredericksburg.

* * *

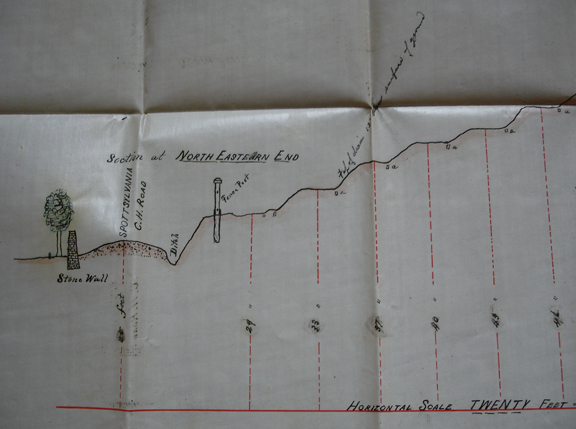

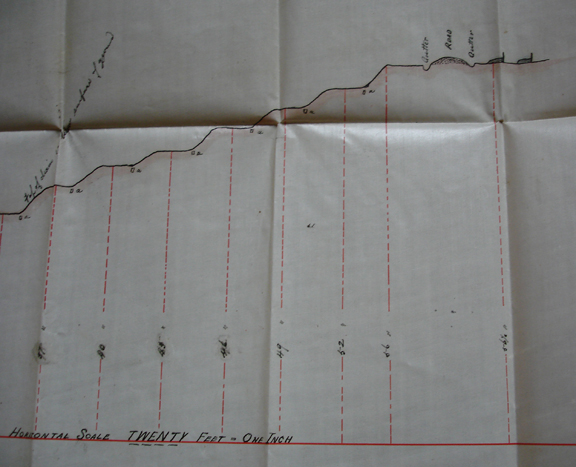

These two images together show a cross-section of the national cemetery at its northern end. The “Stone Wall,” in the left image, runs along the Spotsylvania Court House Road, better known today as the Sunken Road. Above the road, to the right, appears a fencepost marking the eastern boundary of the cemetery. The terraced hillslope extended from the fencepost to the crest of the hill, ending at the main carriageway, which ran around the plateau. Ditches, or gutters, ran along each side of the carriageway. The two objects to the right of the carriageway represent mounded graves with headboards.

* * *

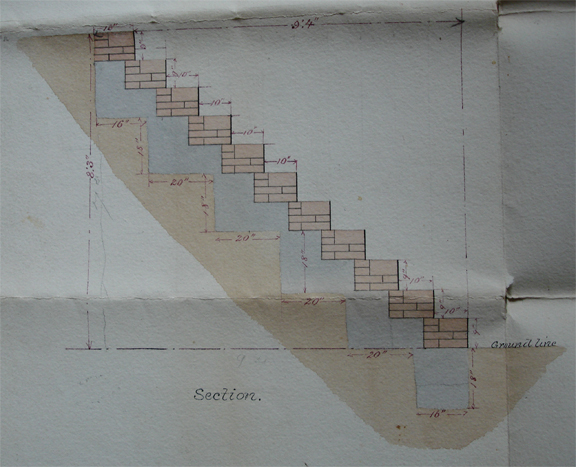

A cross-section of the brick steps located on the terraces.

* * *

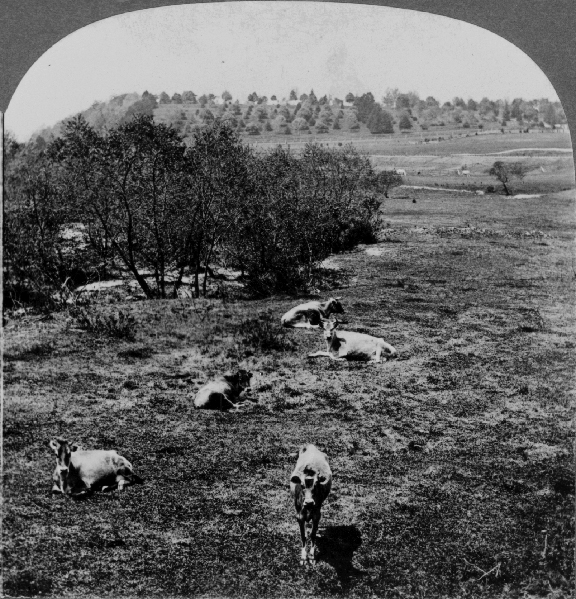

The national cemetery appears in the background of this photograph, taken near the point where the Richmond Stage Road crossed Hazel Run. The Moesch Monument, erected in 1890, appears on the crest.

* * *

This hand-drawn plat of the cemetery, drawn by surveyor James G. Reed on May 7, 1873, shows several interesting features. The circle at left was reserved for the proposed “Soldiers Monument,” which was never built. The smaller circle, in the center, was reserved for the cemetery flagstaff and later became the site of the Humphreys Monument. Inside the “grassy triangle,” at right center, are trees and the outlines of several geometric shapes representing flowerbeds. At the bottom right is a cluster of structures including the greenhouse (G.H.), lodge (L.) and tool house (T.H.). The circle between the lodge and the tool house represents a cistern. A spring appears along the cemetery’s eastern wall, at the bottom of the plat.

* * *

This image was shot from the upstairs window of the caretaker’s lodge. In the foreground, on the left, stands a tablet containing a verse from Theodore O’Hara’s poem, Bivouac of the Dead, which dates the image to ca. 1883. A laborer cuts the grass on the uppermost terrace accompanied by a child, while in the foreground, at right, a woman dressed in black poses for the photographer. This woman, who appears in two other images taken at the same time, is perhaps the wife of either Superintendent Charles L. Fitchett or Superintendent Andrew J. Birdsall. Julia Birdsall is one of twenty women buried in the cemetery.

* * *

A modern view of the south terraces.

* * *

In 1873, Major Edward P. Doherty won a contract to erect granite headstones in the cemetery. Eight years earlier, he had led the detachment that captured and killed assassin John Wilkes Booth.

Additional Resources

On July 20, 1867, The Southern Opinion, a Richmond newspaper, published the following article on Fredericksburg National Cemetery.

The National Cemetery.

To the east of Marye’s Hill, towards the railroad, has been raised the Golgotha of the Federal dead – the national cemetery. It embraces seventy-five acres, enclosed by a substantial and not altogether unornamental railing of wood. The main entrance, opening towards the town, I surmounted by a Gothick gateway, painted in mourning colours – black and white. A tall flag staff stands upon the most elevated eminence, but no flag floated from its pinnacle. The burial corps is still busy here, as it has been for a year past, and their tents dot the hills and valleys round about. We inquired of the superintendent the number up to this time brought into the gloomy “bivouac of the dead,” and learned that it was trifle under fourteen thousand! This number includes all sacrificed in the battles about Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. The dead of the “Irish Legion,” of whom about three thousand fell in the assault on the hill, are gathered here, and they lie together as nearly as possible, their graves drawn out in squares and platoons, in which military order they made their last charge.

A dilapidated ice house, knock in pieces by shell, was pointed out to me by one of the burial corps, as a spot from whence was removed fifteen hundred of the dead of the “legion.” The removal was commenced in midsummer –July, 1866 – but was suspended on account of the tremendous effluvia which the movement of the corpses created. The work was renewed in midwinter – last December – and completed.

An incident connected with the interment of the “Irish Legion” in the cemetery, and which was alluded to by one of the burial corps, is the report that comes to us from the far West, that its late gallant and impetuous commander, General Meagher has recently drowned at Fort Benton. He has gone to join his “Legion,” now marshaled in ghostly phalanx upon the Plutonian shore.

The article, one of the earliest about the cemetery makes several interesting observations. It confirms that the collection of remains was largely complete by the summer of 1867, identifies the colors of the original gate as being black and white, and notes that the removal of corpses from Fredericksburg Battlefield was postponed from July to December 1866 because of the process created “effluvia,” which probably tainted the local drinking water. The articles reference to the “Irish Legion,” actually refers to the Irish Brigade, which Brigadier General Thomas Meagher had commanded during the Battle of Fredericksburg. Meagher was serving as governor of the Montana Territory on July 1, 1867, when he fell overboard from the U.S.S. G. A. Thompson, and drowned in the Missouri River not far from Fort Benton.

The “dilapidated ice house” referred to by the author belonged to the Wallace family, owners of the house known as Federal Hill, which stood on the outskirts of the city. Numerous sources confirm that hundreds of Union soldiers had been buried there immediately following the battle; however, today just 16 of those individuals are identified as being taken from that structure. The final disposition of the others is unknown.

The article makes several interesting statements. First, it gives the colors of the original gate. Second, it suggests that the dead at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville may have been brought in before those of Wilderness and Spotsylvania. And third, it confirms that the Wallace ice house contained hundreds of Union dead, though it still doesn’t answer the question of why they don’t appear in the original cemetery registers. Most intriguing of all, perhaps, is the statement that the Irish Brigade dead were “drawn out in squares and platoons,” whatever that means. The fact that he says 3,000 Irish fell in the attack casts some doubt on the accuracy of his statement, however. Nevertheless, a great article!